Blu-ray Review: Censor – “An unusual and compelling addition to Brit-horror”

Directed by Prano Bailey-Bond

Starring Niamh Algar, Nicholas Burns, Michael Smiley

I read good things about Prano Bailey-Bond’s Censor last year and have been eagerly awaiting a chance to finally see it – fortunately, the always-reliable Second Sight crew are bringing out an impressive limited edition Blu-Ray at the end of January, so I finally got my chance to watch it. I must confess that, in addition to being a life-long horror fan, I also wanted to see this for personal reasons. I hit my teens in the “Video Nasty” era, before this new, emerging world of home video was regulated by the BBFC in the way film already was, so my friends and I got to watch, well, pretty much everything (and despite the rants from people like Mary Whitehouse about how they were affecting Impressionable Youth, none of us grew up to be serial killers), so this is an era and films I have strong memories of.

Years later in the 90s I used this period and the frantic, illogical, tabloid-driven, whipped-up fears (what academics like Cohen have called “folk devils and moral panics”) for some of my college essays on censorship. Even a free, democratic society probably requires some censorship and classification, to protect vulnerable groups, both in the viewing audience and those making the films. But it’s also unhealthy for freedom of speech, and viewing for adults to be dictated by the screaming “outrage” headlines of tabloid media and small interest groups (this would recur again in the 90s and affect even a film-maker of the stature of Oliver Stone, with Natural Born Killers being denied a BBFC certificate due to tabloid pressure, only to be passed pretty much as is a year later once the furore had passed, pretty much making it clear the censors didn’t just work to a list of categories as they said, but also to media jackals, which is worrying).

Enid (Niamh Algar), is in the middle of this era and the growing media controversy (carried out on the airwaves and the red-top tabloids for the most part – this is long before social media and the internet), working as a censor in the gloomy offices and viewing rooms in Soho. A very buttoned-down (almost literally, going by her wardrobe choices) person, she seems to eschew any close connections to her work colleagues (bluntly cold-shouldering a very gentle colleague who clearly likes her, and not caring about the hurt she causes him), and as we learn, her relationship with her parents is distant and strained; it feels like there is nobody in her life at all, just the work, to which she is committed, telling her mother that she is “protecting people”.

As we get further into the film, though, it becomes clear that at least some of Enid’s detachment is a form of psychological withdrawal, from a traumatic childhood event that she has largely blocked most of the details of from her mind, involving her younger sister going missing in the woods. Enid was the last one to be with her, but even as an adult she claims she can’t remember what happened. After so many years her parents, obviously deeply worried about her ongoing refusal to face what happened and get on with her life, tell her they have finally sought permission to have her sister declared legally dead, in the hope that drawing a line under this long trauma will help her to move on too, but instead it seems to have the opposite effect. This also dovetails in a storm caused by a high profile murder case, in which the perpetrator claims a scene in a film inspired his crime, a film which Enid viewed and passed, placing her right on the front-line of frantic protest (doorstepping hack journalists, even threatening phone calls).

This could be enough to threaten the mental well-being of anyone, no matter how stable, but for Enid it’s cracking the emotional-distance armour she has built around herself since her young sister vanished all those years ago. And then more fuel to the fire: sleazy, sexist producer Doug Smart (brilliantly played by the always excellent Michael Smiley), in-between leering at a disgusted Enid, tells her the famous (or infamous) horror director Frederick North has personally requested she be the one to view and advise on ratings for an older film of his, Don’t Go Into the Church. A film with a plot that triggers Enid with flashes of memory – is this film based on what happened to her sister? How could it be? But what if her long-gone sister isn’t dead but was kidnapped and being used in grindhouse films like a film-slave?

As to where it goes from there, I will not spoil it for you, but suffice to say Bailey-Bond does a sterling job of cranking up the tension, while also adding to it by having it shown in such a way as to make the viewer wonder, is this an already damaged Enid finally breaking and embracing a dangerous fantasy, or are some of the increasingly surreal and sleazy producers and directors she has to go through to try and track down North and confront him indicators that yes, there really is something horrible going on behind the fictional horror of the video nasties?

The film drips with loving attention to detail and homages to that period and the wave of horror films that were unleashed onto then-new home video boom of the 80s – even the opening Film4 and other logos get the 80s styling and the dodgy, wobbly video tracking and static burst of a bad VHS tape starting up, and the smaller screen format (the film itself apparently used a mix of 24mm film and video footage, giving it a very period visual feel). The cinematography, by Annika Summerson, is excellent, as is the use of some of the sets: the enclosed, claustrophobic, almost windowless BBFC officers and the even more enclosed viewing booths and the lighting used in them feeds a feeling of alienation, wrongness and disconnection. Some of the scenes, both in the main narrative and in the segments of films being viewed by the censors, also hint at loving homages to older horror films (certainly feels like a couple of scenes tip the hat to some vintage Cronenberg, for instance). An unusual and compelling addition to Brit-horror, and even more fascinating for those of us who remember those 80s video horror nights.

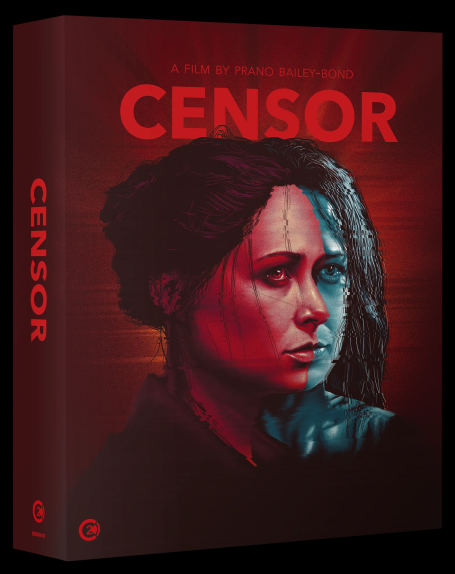

This limited edition Blu-Ray release from Second Sight comes with new artwork (by James Neal), a book with a number of relevant essays and production photographs, collector’s art cards, three options on commentary tracks (including one from Prano Bailey-Bond), a making-of, deleted scenes, a whole smorgasbord of interviews with cast and crew and documentaries on the Video Nasty scare and the resulting media-stoked Folk Panic.

Censor gets the limited edition Blu-Ray treatment from Second Sight on 31st January.