Filed From the Middle East: Robert Fisk and Yung Chang talk about This is Not a Movie

As the COVID-19 pandemic causes film festivals around the world to forgo red carpet premieres for online editions, Trevor Hogg revisits the 44th Toronto International Film Festival with a series of interviews…

For over 40 years Robert Fisk has been covering civil unrest from the streets of Belfast to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, conflicts in Bosnian and Kosovo, wars between US and Iraq, and the Arab Spring uprisings. Presently, the internationally acclaimed British journalist lives in Beirut as The Independent’s Middle East correspondent and recently collaborated on This is Not a Movie with Chinese Canadian documentary filmmaker Yung Chang (Up the Yangtze) who follows him as he has reunions and chases down leads in an age where most of the news is read digitally rather than from the printed page.

Being the subject of the story is familiar territory for Fisk. “I’ve done other documentaries, like my life in Northern Ireland which was more valuable than I realized in terms of seeing how I worked then, and a TV series for Al Jazeera about what it was like to be a correspondent in Herzeg-Bosnia. When I was at school, I wanted to be a film critic which I did for two weeks before the Kent Life went bankrupt. I’ve always had an enormous interest in film.” There were some reservations about the project because of past experiences. “With my documentary series Beirut to Bosnia, they had promised to just follow me around; however, the director became extremely dominating. ‘Get in the car. Drive down there.’ It might have been a little bit my fault because I wanted that film on real film. I would be chatting to someone about some events in South Lebanon and he’d say, ‘I’ve got to stop you. It’s getting expensive.’”

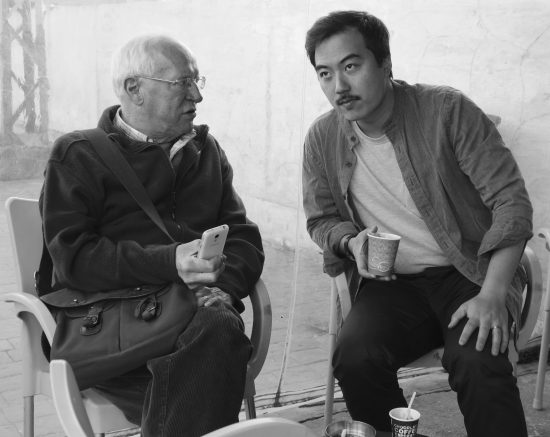

Robert Fisk and Yung Chang

Seated with Fisk during the 44th Toronto International Film Festival is Chang who explains, “My hope was we weren’t blocking the way you were reporting; that was something you established early on and is what became the method. There is an advancement in technology that may have helped us to accommodate you when needed.” Another factor cemented the partnership for Fisk. “Yung came to Beirut on a recce and Duraid Munajim [cinematographer] was there who is Iraqi so he knows more about the Middle East than me and gets along well with people.” It was important to be sensitive to the cultural differences. “Most Western reporters who arrive for the first time want to tell people in the Middle East what is going on. Yung didn’t. There is a brief dinner sequence with friends that was on the recce and I noticed he didn’t say a word. Afterwards Yung asked some straightforward questions and didn’t comment on them. I thought maybe we could do something with this. It would be interesting.”

“I came in intimidated the first time I went to meet him and not knowing what to expect of this legendary Robert Fisk,” admits Chang. “I know that Robert dislikes that. The Middle East correspondent for 40 years. That’s a lot of knowledge to walk into and me being the green one not knowing anything. But the feeling of, ‘He’s a character you would want to watch in a movie because he’s funny and serious.’ And to watch him open up and reveal his process is what we wanted to capture. To know that he was willing to do that as long as we didn’t get in his way. The Bosnia film was the one we used archivally in the movie.” Fisk interjects, “It’s a beautifully made film.” Chang continues, “Thankfully they shot it on film [back in 1993]. It was all good. The Belfast footage was 1972.”

Fisk laughs, “The British soldiers are angry. It’s exactly what I suffer from now! The Beirut-Bosnia thing is interesting. The sequence that you see from the old film where we’re over Jerusalem’s city walls and move over to the settlement; that was from a helicopter. We had persuaded an ex-Israeli helicopter pilot to fly for us. I was sitting up there thinking, ‘What a picture!?’ Today, you would just run a drone over it for just a few penny, whereas thousands of dollars was spent to hire that helicopter. I knew Yung wasn’t going to do a repeat version. It would be insanity. There were a few moments of great humour like he put the wrong lens on or the sound wouldn’t work. I’d used to say, ‘Pitiful.’ But then again, I remembered it’s like me running out of ink in my pen. ‘Oh, fuck! Who’s got a pen to lend me?’”

Finding the footage to go along with the cassette tape audio for when Fisk hears gunfire and starts running was an odyssey. “I was involved in helping to find that,” recalls Fisk. “I used to do a weekly Sunday morning CBC report from the Iran-Iraq war. 10 or 15 minutes. It went to London. It was sent by Radio line to Toronto. I was on the Shatt al-Arab River. When you hear me say, ‘One, two, three.’ I’ve got one of those old CBC tape recorders. I’m setting the dial. I recorded this as sound and it went to Canada that way. At the time Gavin Hewitt and a BBC crew were with me. I contacted Gavin Hewitt who still works for the BBC today. Gavin gave me a name of a guy who specializes in World War II footage and how to find it. He got four reports of Gavin Hewitt on the Shatt al-Arab River on the right day and sent them to me. We put them on and I said, ‘Christ it’s me running! It was the exact moment when I was doing the report. We were able to sync up my actual recording from the time with a picture of me from Gavin’s BBC cameraman.” Chang is still amazed about the discovery. “ It’s one of those remarkable moments of finding lost footage. It’s a needle in a haystack. I don’t know how he found it.”

When it comes to the cost of getting the rights to archival footage, Fisk responds, “Don’t tell me about that! That’s not my problem. I have an archive of taped pictures on my own film at home which I said he could use and a vast paper archive of clippings, dates and times.” Chang elaborates. “We leave that to the producers. It’s extremely expensive. We knew that this film would be built around the present-day storyline and go seamlessly back and forth to the past. We had some great archive with the Beirut to Bosnia film and the BBC reporter documentary from 1972. The Times of London documentary with Murdock was a wonderful find.” The voiceovers were not derived from past writings. “Those came about because we were filming the actual event unfolding, as Robert was investigating the report; the end result would be filed with The Independent.” The street interviews were spontaneous. “Afterwards because of this complex system that you people wretchedly have, they have to sign their permission which I don’t have to do,” remarks Fisk. “They know that I’m Robert Fisk. You’re going to be quoted in The Independent. Everyone signed a release form including the guy in the Bosnian arms factory. It all worked out! I never got the end user certificate.”

Over the years Fisk has been criticized for his political commentary. “Either you can’t see the forest through the trees or you’ve gone native. You can’t win.” The British journalist came under fire for the suggestion that America was not entirely blameless when it came to the 9/11 attacks. “Jean Chrétien [Canadian prime minister at the time] got close to it when he made a comment about this is what happens on Wall Street and with Western policy. The best example that I can tell you, which has nothing to do with the film, is during the liberation of Kuwait in 1991. I was in the desert with arid farmers. I didn’t get embedded with the U.S. Marines or the British Army. The Americans had blocked off the main road up to Kuwait City because they feared all of the oil would get burned. I asked some Kuwaitis and they were like, ‘Come with us. We would like to have a Western reporter. We could talk to each other.’ I was in Saudi Arabia and travelling around the frontier of occupied Kuwait. I got a lot of stories about what the Americans were doing wrong and how an entire British unit tried to drive into the Iraqi frontline without realizing it. On this occasion, many letters were sent to The Independent editor by real readers demanding that I either be censored or fired. They wanted the government version not me. I was out there risking my life and there were shells falling near. I was thinking, ‘My own fucking readers didn’t want this stuff. What did this mean?’”

There is too much of a reliance on the Internet for information. “Buy a few books and check it out,” notes Fisk. “There’s a Wikipedia on me and it’s filled with factual errors. Friends have said to me, ‘Why don’t you correct it?’ I said, ‘I don’t care. Do you trust Wikipedia?’ ‘Many people read it.’ ‘I don’t care. I can’t sue them for libel. I don’t know who wrote it and I don’t care. As far as my view of the Internet even Google, get the laptop, tip it over, pour it all out, and write.” Chang is of a similar mindset. “My view on that is to go to The Independent and read Robert Fisk’s column. I like this site called Z Magazine and go there to read articles by Norm Chomsky and people like that. Looking for places that are reliable, otherwise it just is noise of information. Maybe the future of the Internet is finding these places that officially we can trust. Newspapers are still a place that you can go to start.”

The Independent has become an entirely online media outlet. “We went website because we couldn’t make it,” reflects Fisk. “I suspect that newspapers will come back. When The New York Times went on about fake news, I said, ‘The New York Times has been running fake news about the Middle East for decades. Why are you getting so worried about Trump? This is nothing new.’ The accusation against The New York Times by Trump is a lie but the fake news is not a lie. I don’t know the way out of this. People came up to me last night and asked, ‘How can we change the Middle East?’ I said, ‘Get on a plane, go there, talk to people, come back, and tell all of your friends.’ Journalist shouldn’t do 50/50 journalism. Half to the Palestinians and half to the Israelis. Half to the Americans and half to the Iraqis. In the same way, we cannot oversee our own profession. The same goes for films. We can produce something that makes people say, ‘Jesus Christ!’ But then it’s up to them to decide.” Fisk gives voice to the disenfranchise in his writings. “It’s up to the people to have the elected representatives represent them. I don’t do advocacy.” Chang adds, “We’re not making an advocacy film. The goal is to provoke an audience, to make them think and ask questions.”

Special thanks to Robert Fisk and Yung Chang for taking the time to be interviewed and for more information visit the official website for the National Film Board of Canada. This is Not a Movie is available in Canada through D.O.C. streaming.

Trevor Hogg is a freelance video editor and writer who currently resides in Canada; he can be found at LinkedIn.