Blu-ray Review: Walkabout – “A waking dream on celluloid”

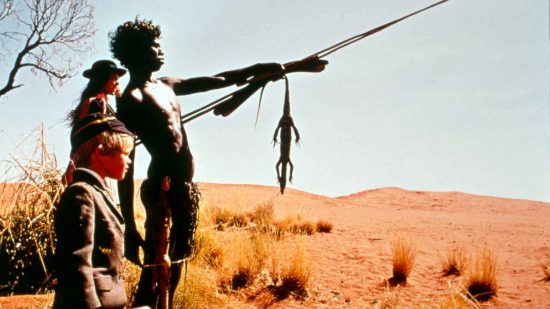

Starring Jenny Agutter, Luc Roeg, David Gulpilil

Directed by Nic Roeg

During the Lockdown, BBC4 in the UK broadcast David Stratton’s “Stories of Australian Cinema”, a three-part documentary on the history and evolution of film-making in that vast, continent-sized country. Naturally one of the films covered was the legendary Nicolas Roeg’s 1971 movie, Walkabout and I’ve had a strong urge to revisit this film since watching the series. And then Second Sight announced a limited edition Blu-Ray of Walkabout (packed with extras, including interviews with Jenny Agutter and Luc Roeg, in a box set complete with James Vance Marshall’s original 1950s novel), and there I was losing myself in this classic again.

Both then and now there was some debate, not least in Australia itself, around whether Walkabout is really an Aussie film – a British director, US money, but shot in Australia. For my money, it is very much an Australian film, not just because of the location, but the way Roeg makes that vast, ancient land an important part of the film. These are not just locations for a scene, the land itself often is the scene or a strong part of it; the small-scale human interaction within it may drive the actual narrative, but the land itself surrounds everything they do and say, the two English children (Agutter and a very young Luc Roeg as her small brother) in their school uniforms and prim, plummy accents, outsiders in an environment they not only don’t understand but aren’t really equipped to even really try to comprehend, Gulpilil the Aboriginal boy on Walkabout, brought up to respect the land, the stories that go with it, that form his culture and his guide to survival.

The story is essentially pretty simple – the two children, Agutter and Roeg – are stranded in the Outback desert when their father, who has driven them there for a picnic, loses his mind and attempts to kill them, before setting fire to the car and taking his own life. Agutter hides the suicide from her young brother, grabs some of the food and the two start walking. But they are from a city environment, and a strata of society that back then still had a middle-class that basically tried to recreate the middle-class English existence, there’s no attempt to adapt and assimilate into this other country, it is more an attempt to push transplanted cultural imperialism onto it, and means they haven’t the faintest idea about the vastness of the Outback, much less how to survive (when they encounter Gulpilil Agutter asks him for water. He doesn’t speak English so she simply repeats herself as if speaking to an imbecile, before muttering that she can’t be any clearer. It’s a polite version of the modern, monolingual Brit abroad who thinks if they shout loudly in English the other person will understand them somehow).

The good-natured Gulpilil communicates with them through mime and gesture, mostly with Roeg’s younger brother, the two forming a bit of a bond together. Gulpilil generously helps the pair find water and shares his hunting kills with them, slowly guiding them back towards their own world after some shared travels. You could see it as strangers in a strange land fable, as a coming of age story (especially Agutter and Gulpilil, the two teens on the cusp of adulthood and all that brings with it), or as a survival story, or a mix of all three. And indeed yes, Walkabout is all of these things, but really, those are just the skeletons the film is draped over.

No, the real essence of Walkabout isn’t really those elements, it is a wonderfully-realised dream-like state, using clever imagery, symbolism and cross-cutting and editing, to create an atmosphere and imagery that is as rich as the Outback environment itself, a filmic version of the ancient Songlines and Dreamtime of Aboriginal culture, sometimes languid, like the dream of a half-waking doze on a warm day, sometimes sudden, even violent, mixing Aboriginal culture (Gulpilil, already an experienced dancer despite his young age here, crafts an intoxicating scene entirely through traditional dancing) and allusions to the Garden of Eden, innocence and its loss, nature and the urban.

This isn’t a film that is easy to review, because it’s more than a film, Walkabout is an experience, a waking dream on celluloid that can be shared, and how each of us reacts to those images and sounds will be different. It is a film to lose yourself in, to drink in those rich images, that landscape and nature. A commercial flop on its original release, it remains an important film, lauded by many critics and the BFI as a classic – it helped to kickstart the new wave of Aussie film-making which has gone on to enrich world cinema (something we here obviously care deeply about), and it launched the then-young Gulpilil onto a career which has seen him become an iconic figure in Australian cinema. If like me, you haven’t seen this film in a long time, this is a very welcome chance to revisit this moving dream of a movie; if you haven’t seen it before then sit back and let this classic wash over you with its rich imagery.

Walkabout will receive a limited edition Blu-Ray release from Second Sight from 31st August 2020.