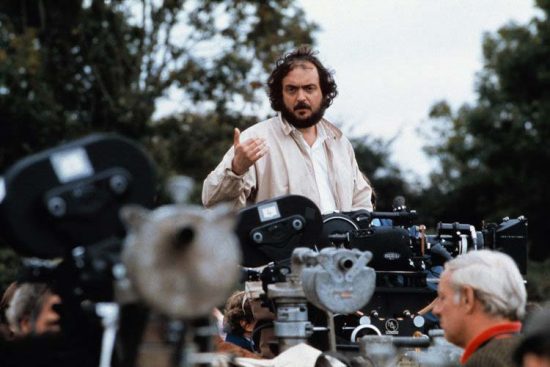

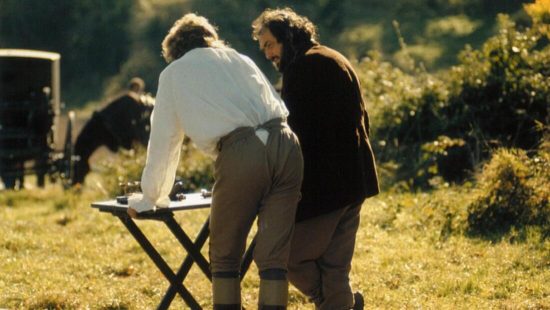

Stanley KuBLOG: Barry Lyndon – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Barry Lyndon is Stanley Kubrick’s tenth feature film. It came after a series of magnificent successes capped by the trauma of A Clockwork Orange, a film that Kubrick withdrew from distribution in England after death threats. The handsome adaptation of William Thackery’s lesser-known novel was greeted with praise for its technical accomplishments, but the film did not enter into the intellectual conversation of the time the way his previous three films had, nor did it win over large audiences, who perhaps not surprisingly preferred the more bite-sized Jaws.

Not being an overwhelming success for Kubrick was like an abject failure. He might bravely recite the European awards the film picked up and the praise garnered from intellectuals at the time to Michel Ciment, but the fact of the matter was, compared to every film he’d made since Paths of Glory, Barry Lyndon was something of a disappointment. For some, even for its supporters, Kubrick’s film was slow, ‘painterly’ – a word critics are legally obliged to use when discussing the film – cold and featured a bland performance by Ryan O’Neal. And in retrospect, it seemed the beginning of a decline. No film made afterward, and each with a greater interval from the last, from The Shining to Eyes Wide Shut, would achieve the unambiguous acclaim which he had once seemed to effortlessly win.

And yet, watching it over the years, I have changed my mind about this film almost totally. I had previously ranked it as a flawed masterpiece, now I’d ditch the qualifying adjective.

First of all the film is funny. Although not the Tom Jones-esque romp the studio had been expecting and one of the posters seemed to suggest, the film is full of fantastic comic performances. Leonard Rossiter’s clownish officer, Steven Berkoff’s fingertip kissing fop, Patrick Magee’s chevalier, the Reverend Runt, the highway robbers who pride themselves on their fairness and politeness. And the way money is mentioned all the way through the film stands as a wry running joke. From the courtship of Nora (by Quinn who’s worth ’15 hundred a year’) through the soldier’s bounty and the gambler’s winnings to the final shot of Barry’s annuity being signed over, money is a motivating factor for almost everything that is done. Even Bullingdon sees that he has let a fine fortune go to ruin, as well as having seen his mother dum de dum de dum.

In the context of the broader comedy, O’Neal’s performance makes sense. He’s the tragic magnet towards which all the comedy is attracted; the quiet centre around which all else revolves. Watch the scene in which Redmond Barry disguised as an officer has a romantic candlelit dinner with a young German girl who’s taken him in. The two adults speak lines that are obviously a conventional romantic prelude, but the baby gives a comic performance as it gets increasingly irritated at not being fed. The summary given by the narrator seems needlessly cynical and cruel. Barry is not a rake and the woman is obviously not a strumpet, but the narrator wants them back firmly in their respective boxes.

The progress of Redmond Barry is one step forward two steps back. The narrator, who seems at times to hold a grudge against Barry, repeatedly tells us that Barry decided from that time forth never to slip from the sphere of a gentleman, only for him to do exactly that. Even at his height, the title card that introduces Part Two of the film anticipates his decline. O’Neal plays Barry with a quietness all the way through. He has the eyes of a man who knows even at the height of his success that he is going to be found out. The look, for example, he gives George III who has dismissed him and all his efforts. He is an orphan, an outlaw, a deserter, a parvenu and, importantly, an Irishman. We never see him do anything particularly bad, except perhaps chastise Bullingdon his stepson, but in the thinking of the day his actions would not have been controversial. In fact, in the end, he’s remarkably generous in not killing Bullingdon. A lovely detail in the duel is the fact that the only close up of a detail comes with the bullet being put in the barrel of the pistol, to reassure us that unlike the second duel we saw, this is not going to be a fix-up fought with plugs of tow.

Many growing up with Kubrick’s films as a reference point might – like me – have gone through a similar trajectory of initial dislike, or lukewarm admiration on first encounter, giving way over the years of rewatching to wonder and something like love. Of course, the film is gorgeous with its mixture of landscapes, handheld violence, perfectly composed portraits, and candle-lit scenes of chiaroscuro nightlife, captured by the masterful cinematographer John Alcott. The music from initial Gaelic airs to the delicate melancholy of Schubert – an allowable anachronism – and the final knocking of fate that is Handel’s beefed-up Sarabande confirms Kubrick as one of the deftest scorers of his own films.

Finally, something must be said about the film’s reputation for coldness. Partly this comes from Kubrick’s own interviews and his reputation as a chess-playing manipulator, but within the film, there is also the aloof narration, the growing cynicism of Barry himself, and those slow contemplative zooms. Barry blowing smoke in his wife’s face is a horrible image of cruelty and indifference, but we see it as exactly that. And the outbursts of genuine emotion are all the more sincere for being so long suppressed. Barry’s original injured love for Nora, his joy in befriending the Chevalier (Patrick Magee) and ultimately the grief at the death of his son are all beautifully played (O’Neal would never be so good before or since) and feel utterly sincere. Barry Lyndon is a rich cinematic experience that fully deserves to enjoy its status as one of Stanley Kubrick’s greatest achievements.