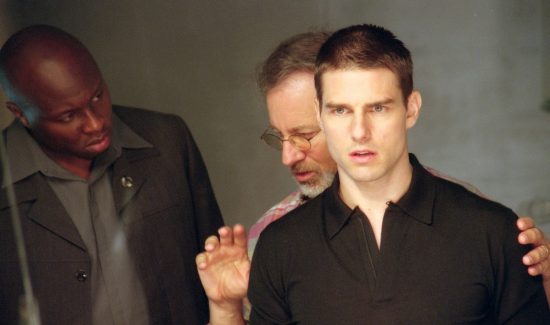

SpielBLOG: Minority Report – A Steven Spielberg Retrospective

There’s something fresh and invigorating about Minority Report. Based on a short story by Philip K. Dick, the film was Spielberg’s second consecutive science fiction drama after A.I. Artificial Intelligence and would begin a two film collaboration with top movie star Tom Cruise. Originally conceived as a direct sequel to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Total Recall in the early 90s, there were extended delays until it saw the light of day in 2002.

Cruise plays John Anderton, a policeman in charge of the PreCrimes unit, a Washington based elite police squad that prevents murders – detected by three pre-cogs – from ever taking place. The team is under pressure as the initiative, under the supervision of Max Von Sydow, is due to go national and a special investigator (Colin Farrell) has been called in to investigate.

Anderton is in a particularly sensitive situation. Although a top cop, his personal life is a shambles, following the disappearance and presumed murder of his son. He’s obsessed with his job – which he believed would have prevented his son’s abduction – but is separated from his wife and addicted to vaping drugs.

Anderton has the tables turned on him when the pre-cogs predict he will commit a murder of a man he has never met and he will now be hunted by his own team. This classic reversal is in line with the feel of the film. Although technically in colour, the film is so desaturated and overlit as to almost count as black and white. As A.I. was in many ways an old studio melodrama, so Minority Report hails back to the classic noirs which Spielberg watched in preparation to filming. And yet the film can’t really settle on a tone. There are so many elements contending. The action thriller aspect is given two or three set pieces and then largely disappears. There are grotesque comic cameos from Peter Stormare and Tim Blake Nelson, and a really strange swerve into gross-out comedy that would be better placed in a Farrelly Brothers film. This all clashes with the more serious themes of grief and loss, predestination versus a lack of free will.

The ending has always been problematic as suddenly we go back to Spielberg’s early TV work on Colombo and get a late in the day exposition dump as all the loose ends are tied together. There is a theory that the last act is actually a dream that the imprisoned halo-ed Anderton has and therefore doesn’t actually happen. The problem with this idea is that we tend to dream subjectively. See Terry Gilliam’s Brazil for how this is done effectively. In my view, this is a reach to prop up what otherwise is a melodramatic and disappointingly cut and dried ending. I remember on first seeing the film thinking that the film should end with him killing Crowe and realizing that he is capable of murder. That ending would have had the effect also of playing on and subverting Cruise’s heroic stature as a film star.

But actually the ending is also completely in keeping with the old fashioned moral that would be tacked onto otherwise dark and ambivalent material. Look at how in Psycho a scene with an explanatory psychiatrist almost ruins everything if it wasn’t obvious you weren’t meant to take any of it seriously. And as the film has settled and matured, it is now possible to see just how many ideas Spielberg is playing with. The overhead shot of the scuzzy motel where the spiders search for Anderton is a good example, but the film is stuffed with them. The VR brothel where one customer is discovered just being surrounded by people congratulating him; the adverts which talk to you; the newspapers which change with Breaking News: some of these predictions feel prescient – the product placement of Nokia, less so.

It is also worth seeing Spielberg’s film as a mix of Aldous Huxley and George Orwell. There is a police state but mass surveillance is designed to entice you to buy new khakis at the Gap. (People are still shopping at the Gap?) There is a happy, smiling form of consensual unfreedom with the problems buried out of sight and out of mind. The exploitation of the three pre-cogs, for instance, goes largely unquestioned until the end. Anderton kidnaps Agatha – from a pool – in the same way his son was snatched. Witwer’s contention that they are somehow divine – he’s an ex-seminary boy – runs throughout but doesn’t afford them any decent treatment as human beings. The fact they are named after crime writers Arthur (Conan Doyle), Dashiell (Hammet) and Agatha (Christie) is a name-check on influence, but it also goes with the theme of the submerged, the drowned, the repressed returning to the present and the now.

‘Everybody runs,’ John Anderton says and it seems like Steven Spielberg was in one hell of a hurry. Having released A.I. in 2001 and Minority Report the following year, he still had another film to release in 2002 and that one was about running too.