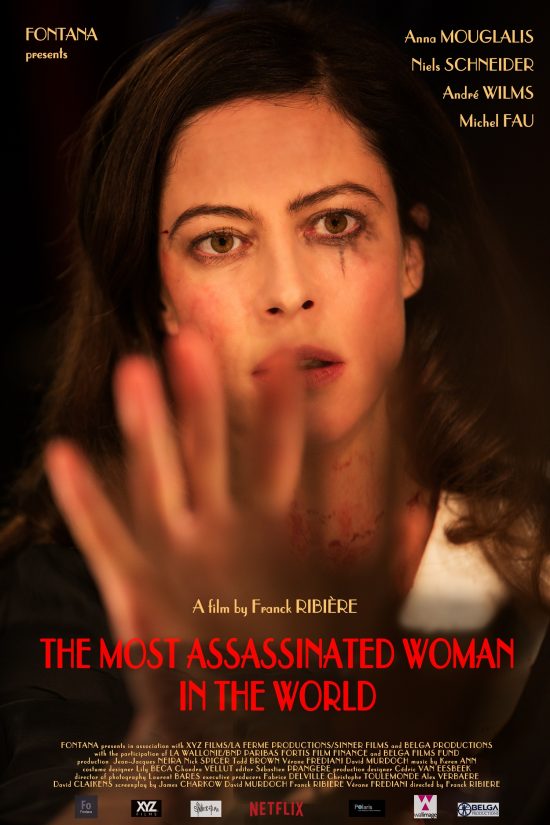

EIFF Review: The Most Assassinated Woman in the World – “Shot in a beautifully sensual manner”

Another evening at the Edinburgh International Film Festival (EIFF)and another intriguing film, this time from French director Franck Ribière, that partakes in elements of murder-thriller, period piece and delightfully lurid horror. Set in the famous/infamous Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol in the Pigalle district of Paris during the 1920s, The Most Assassinated Woman in the World takes real-life settings and historical characters – most notably the theatre’s great scream-queen, Marie-Thérèse Beau, better known by her stage name of Paula Maxa, played by Anna Mouglalis, an actress who was slaughtered in thousands of violent and gory ways every night on the tiny stage of the theatre. It’s claimed she was “killed” some ten thousand times, and early on her character lists many of the ways, from strangling to stabbing, slashing, burning, boiling, decapitation, being pulverised. And yet, she shrugs, here I still am…

In some ways this listing of nightly horrors enacted on the stage of this notorious theatre (which only closed in the 1960s) and the fact that Paula “survives” it all and keeps going is part of the central theme here: we were told in the post-screening Q&A with the film-makers that they were not aware of a violent assault Paula had endured in her younger years, and yet they had written such a scene in affecting her and a sibling, in an uncanny moment of art imitating life. They were exploring the nature of horror and violence, how it affects people, even the pretend violence of the horror on stage or in the movies, both those who watch and those who act it out (imagine being an actor having to be killed in inventively gruesome manners every single night). Experimental psychologist Alfred Binet, another real-life character involved with the actual theatre, is also, appropriately, a figure here, helping owner De Lorde construct not just physically awful torments and demises for Paula, but mentally brutal as well, pushing, pushing, pushing, aided by the giant figure of Paul, the special effects wizard (another real-life character, apparently his stage blood formula is still used to this day).

Mixed into these factual elements are more fictional dramatic ones – a young journalist from Le Petit Journal, Jean (Niels Schneider), investigating both the moral brigade demanding the theatre should be closed for indecency (forerunners of later “we should control what everyone can see, for their own good” types that burned rock and roll records or the Mary Whitehouse mob) but also a series of disappearances and murders around the Pigalle and Montmartre areas (loved by tourists today, but rather rougher back then). Is the murderer inspired by what he sees on stage, is it driving his fantasies to act them out for real? Who are the figures haunting Paula? Does her work help her excise her own demons or is it all pushing her to the brink – and do those in control of the theatre even care or are they happy to push beyond the limit?

The film is set in mid 1920s Paris, but the cobbled back streets, the heels clicking on them through foggy nights, the evening capes, they could all come from a Victorian-set Hammer film, and the gallons of luridly red “Kensington Gore” as the blood flows scarlet stands out against the dark, mostly nocturnal scenes, as vivid a claret as ever flowed in a Hammer film. Interestingly the film-makers told the festival audience that originally this was to be an English language film, set in New York, but as they explored it more, found the historical Paula Maxa, it became clear they really needed it to be a French film, set in Paris. They struggled for funding, but a Belgian film fund stepped up, as did Netflix, who they thought would ask for it to revert to the original English language premise, but instead were quite happy for it to be a period French piece.

In fact Franck Ribière commented on the “Netflix issue” which has come up at quite a number of film festivals around the world, most notably at Cannes, where some are glad of the new stream of funding and distribution while many others are horrified and say it is killing cinema with movies going straight to television streaming and bypassing cinemas. I can see arguments on both sides, but that’s a debate for another article, not a review. I will note that Franck Ribière explained he didn’t see the problem. It was another welcome source of funding for film-makers, and nobody makes a director or writer work with Netflix. It is up to them to approach them about partnerships, and that he is happy to be able to watch films as he wants, in cinemas, on TV, on his phone. Many other directors, I am sure, disagree, but it was interesting to hear him comment.

No news on a UK release for this one yet, but as it is co-funded by Netflix I assume it won’t be long before it appears online, so those of you who don’t have a film festival or arthouse cinema nearby will be able to see it too. All in all I really enjoyed this, it offered both the over-the-top horror the Grand Guignol was famed for (and which it has given its name to as a general term in horror now) mixed with a more psychological aspect, and layers of “plays within plays” as we see fictional and real elements of Paula’s life mixed with pretend versions for the film and more pretend but almost real versions on the stage, until we’re left wondering what elements are real, what scenes are what they seem to be and which are theatrical artifice, all shot in a beautifully sensual manner. One of the smarter, classier horrors I’ve seen recently, and yet one which happily plays with elements of classic horror too.

Check out my blog and you can follow me on Twitter.