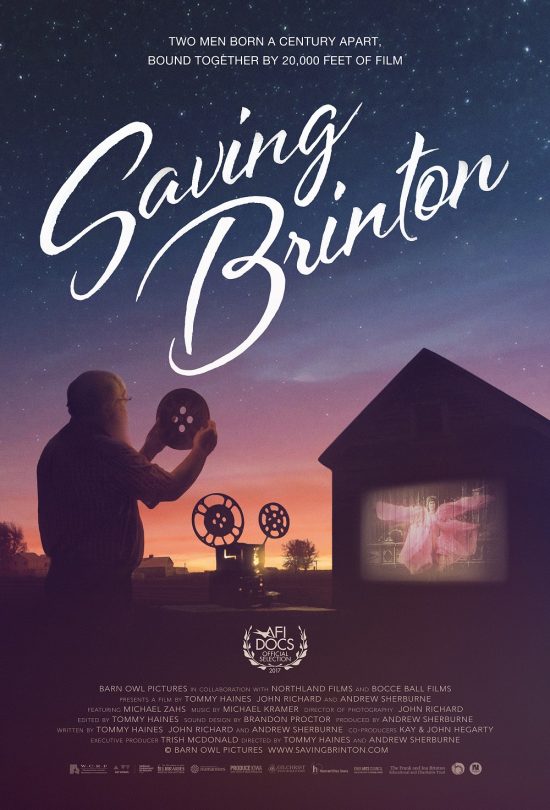

EIFF Review: Saving Brinton – “A must-see for anyone with a passion for film”

Saving Brinton is one of the movies that leapt out at me when I was busy circling the movies I most wanted to try and get tickets for at this year’s Edinburgh International Film Festival (EIFF): a documentary about a man, Mike Zahs, in a tiny Iowa farm town, who just happened to have collected, protected and shared some gems from the very, very earliest days of cinematic history. It’s an irresistible subject for those of us who love film.

William Franklin Brinton was an itinerant showman, he and his wife travelled up and down the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s, from Texas to Minnesota, with shows which included music, gadgets (some of the existing music boxes are preserved in the collection as well as film), attempts at heavier than air flight (several years before the Wright Brothers managed several seconds in the air), some truly enchanting magic lantern slides and, always a sharp showman with one eye on getting those bums on seats, but another eye always on technological innovation, which fascinated this intelligent, curious man, he was an early adopter of the new miracle of the Victorian era: moving pictures. Some, even innovators like Edison who would contribute to the development of the medium, saw film as a passing fad. To be fair, he was not alone, few could have predicted film would grow to be one of the great art forms and mediums of the following century and into the next, let alone that it would become so entangled with our own lives, our dreams, fears, aspirations and hopes.

Brinton saw more in this infant medium, and in a later, more settled part of his career he managed the Graham Opera House in the small town of Washington, Iowa, which has been showing film pretty much since the birth of the medium, and has now been recognised by Guinness World Records as the oldest continually operating cinema on the planet. There is something rather pleasing that such an accolade goes not to some historic old cinema in Paris, or London or New York, but a wee town in the middle of the great farming fields of Iowa, right in the heart of the vast American continent. Once every town had such palaces of delights, but most are long gone in the US, as here, long since converted to other uses or ripped down and built over. Here though, a slice of entertainment history still lives, still serves its community, and for around three decades it has also seen some of the rarest early film works from the Brinton collection projected on its venerable screen.

Check out our EIFF coverage

Zahs, an incredibly genial, modest and charming man with a mighty beard (he looks like Gandalf crossed with Father Christmas, perhaps), a teacher, historian and collector, has been saving and documenting this collection for years, trying to interest the wider world in these treasures. There is a delicious irony that the small community here has been watching films, some of which cinema historians had, for years, lamented as lost, totally unaware of Mike’s collection. But eventually perseverance pays off, local academics from the University of Iowa work with Mike, and as academics do, they bring in other experts, including the Library of Congress. It’s soon recognised that the collection has remarkable works, such as rare moving images of Teddy Roosevelt, the first known film from Burma (how astonishing and exotic would that have seemed to an 1890s audience in an era before television, internet and easy international travel?), absolute gold: works by the first true genius of our beloved cinematic medium, Georges Méliès. Actually, scratch that, Georges Méliès is not so much a genius as a wizard.

All of this “lost” cinematic history being rediscovered as academics finally take notice, increasingly enthusiastically, of what Mike has been trying to show them for years, would be fascinating enough, and the triumph, from only local folks watching to international recognition of the importance of this collection (complete with showbills, photographs, glass slides for the magic lanterns, projectors and more along with the actual nitrate films) is satisfying: Mike goes from showing the works to his local friends and community to an outdoor film festival screening in an ancient square in Bologna, and the international film festival circuit. But there is much more to Saving Brinton than the rare works saved from vanishing into history: this is a film which is as much about people and about community as anything else.

It’s to the credit of the film-makers, Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherburne, that they spend quite a bit of the running time on Saving Briton exploring this small local community, and Mike is their way into this small farming town. As well as putting on shows with Brinton’s films, magic lantern slides (some very sophisticated, allowing for overlaps and dissolves which are still gorgeous looking even to modern eyes used to CGI wonders), we see Mike planting peach trees on the family farm close to others that go back generation in his family, Mike delighting young kids at the local school showing them all sorts of odd-looking historical artifacts from his collection and engaging them into learning without even realising it (always a good trick to play on kids to enthuse them), even giving a talk to some of the local Amish families on local history. As Mike said himself at the Edinburgh screening, the most important part of the word “history” is “story”, and stories are about people. And Saving Brinton shows how that remarkable collection is more than preserved celluloid frames and ephemera, it has been woven into the local communities since 1895 when Brinton took it from town to town.

At the Edinburgh Film Festival screening we were lucky enough to have the film-makers Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherbune present, as well as Mike himself, who seemed utterly delighted to be showing this work at the world’s oldest continually running film festival (quite an appropriate venue for such a subject, surely), and in person he was as delightful and fascinating as he was to watch in the film. As a bonus, after the film and a Q&A we were treated to ten minutes of these very short works – works that, as is said in the film, were made when the people we now think of as the stars of the silent era, the Chaplins, the Keatons, would still have been children, they are that early. These included the “flying machines” which many in the UK will recognise (created by Brinton’s contemporary Sir Hiram Maxim, still flying at Blackpool today), some truly glorious early 1900s colour film (each frame painstakingly hand-tinted to produce the effect, which still looks magical), and treasure upon treasure, a Georges Méliès film which was thought lost for most of the last century, and here Mike and his small town had been enjoying watching it for the last thirty years…

This is just an utterly enchanting, beautiful film about shared history, community, art, lives. Mike and his wife have donated the collection to the University of Iowa Libraries, where it is being carefully examined, conserved and digitally copied so it can be shared. There is a dedicated site for the Brinton Collection run by the university, which I highly recommend visiting for more information and also to find links to watch some of these incredibly early films online, such as the hand-coloured Serpentine Dance and other little gems that were so nearly lost forever, and the official Saving Brinton site has more information. This is an absolutely magical, warm, smile-inducing documentary that is a must-see for anyone with a passion for film.

Check out my blog and you can follow me on Twitter.