Refining the Final Cut: When is a film actually finished?

It can be quite hard to define when a film is truly complete. Ok, so you might think that’s a stupid statement; surely its first widespread release is a significant moment. After all, the shared audience experience is a rite of passage for any film, when audiences first see it, and for better or worse imprint it to the public consciousness and culture forever.

When commercial pressure, audience expectation and artistic freedom clash, this isn’t always the case. In fact, cinema is littered with instances of the exact opposite, where films change after they first hit the screen and multiple versions of the same story exist, blurring the lines between what really constitutes the ‘truest’ version of the movie. Ultimately it boils down to a question; what defines that true version, the director’s intentions or the version claimed and loved by its audience. We take a look at three examples:

Remastered Classics

The ‘remastering’ of films is nothing new. It would be pointless to talk about this, however, without considering George Lucas’ Star Wars. If anything encapsulates the debate and the public backlash to retrospective alteration, this is it. Of course, this ground-breaking space opera has changed across its lifespan, but none as drastic as the 1997 Special Edition versions, which went beyond sympathetic modernisation, adding scenes and most controversially changing some as well.

But this created a rift with the audience. Those who had grown with a particular version of Star Wars felt the changes went too far. In their view not only was Lucas altering the film itself, he was messing with their memories of it as well. So much so, that some fans went as far as creating their own ‘despecialised’ versions.

Lucas certainly isn’t the only director to give their films a modern shot in the arm, justifying his updates as better representing his original vision, which was limited by technology of the time. As creator he has a right to change his original work, but whether the result was closer to the author’s original vision, overzealous perfectionism or commercially driven the jury is still out.

Version Control

Often directors can change their final cut of a film in a much shorter time than a remaster, post exhibition, meaning audiences might see a different version of the same film from cinema to home release.

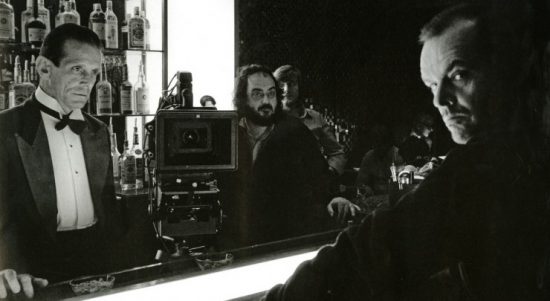

Stanley Kubrick was a director notorious for perfectionism. Famously demanding multiple takes and breaking records in the process, it’s difficult to imagine such a purist director changing his film after release. But whilst Kubrick was clearly a legendary auteur with a singular vision he did respond to audience and critical response, which for his 1980 seminal horror, The Shining, resulted in two different versions of the same film.

Audience participation in the editing process is nothing new, test screenings are considered an integral part of perfecting a film but this is usually before the final cut is agreed. When The Shining was first released in the US, it was met with a mixed critical response. Success for any mainstream release relies on audience appeal so prior to the European release of the film, Kubrick made further cuts editing the length down by 24 minutes and inadvertently creating two versions on respective sides of the Atlantic. Kubrick gave his blessing to both versions but debates around the success of these cuts differ. The question of which version is closer to Stanley’s vision remains unanswered.

Director’s Cuts

Filmmaking is an expensive job with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake and multiple commercial interests exerting pressure an auteurs vision. Something that explains the Director’s cut, both as the antidote to studio interference but also a money-making endeavour.

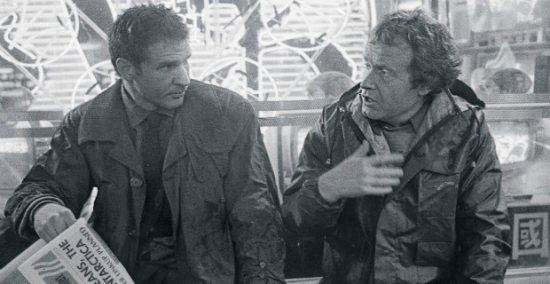

One key proponent of the Director’s Cut is Ridley Scott (notable mention to James Cameron). Famously, Warner Brother’s Executives were left confused by his influential Sci-Fi film Blade Runner, demanding Scott reshoot a more palatable ending and add narration. When the film proved a cult hit on home release, Scott was able to return and refine his directors cut (and has since re-edited his ‘final cut’). Many directors bemoan studio interference but paradoxically, it is mostly the successful studio cuts at the box office or those with cult success that get a director’s cut.

These differing versions are now big business, and whilst often commercially driven allow audiences to spend more time in a world they engage with, for example with Lord of the Rings extended cuts. Are the films better for this, or do they get bloated and weighed down by the additional footage depends from version to version.

Choosing from Multiple Versions

Whilst these are specific examples, there are many more films with similar circumstances. Alternative versions allow a director the freedom to deliver a different vision but every choice they make both pre and post release, has the potential to alter the meaning to its audience. For us cinemagoers it is a double-edged sword, new versions of films offer the expansion of a world we love and indeed, an insight into the editing process, others change things the very things we love and our memories of them.

Ultimately it is a personal choice of which version they engage with most. So if you prefer the Aliens Directors cut, or Spielberg’s infamous ET 2002 remaster then you should celebrate that.

You can follow me on Twitter.