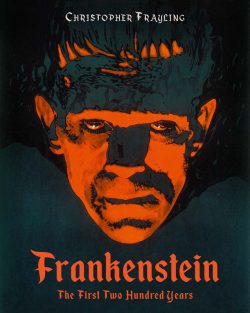

Frankenstein: The First Two Hundred Years is a must for any Frankenstein fan

It all began with a ghost-story contest, a parlour-game, a serious young woman of eighteen years old who had run away with her boyfriend, and some very stimulating company—and a thunderstorm which kept them indoors . . .

It all began with a ghost-story contest, a parlour-game, a serious young woman of eighteen years old who had run away with her boyfriend, and some very stimulating company—and a thunderstorm which kept them indoors . . .

On New Year’s Day 1818, Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein was first published in an anonymous three-volume edition of 500 copies. Some thought the book was too radical in implication. A few found the central theme intriguing . . . no-one predicted its success.

Frankenstein: The First Two Hundred Years celebrates the two hundredth birthday of Shelley’s Frankenstein and traces, in colourful and engaging ways, its journey from limited edition literature to the bloodstream of contemporary culture.

Reel Art Press R|A|P sent me a copy of the book and it is absolutely fascinating. Chock full of so much information, including pages of Mary Shelley’s original notes for the story. Collecting all the various films and TV shows featuring the character in one place shows just what a huge impact the story has had.

Christopher Frayling’s book is the most comprehensive exploration of Frankenstein to date. It includes new, in-depth research on the novel’s origins and a facsimile reprint of the earliest-known manuscript version of the creation scene. Frankenstein’s legacy is to be seen all over the world—on small and large screens, in print and online, on stage and on hoardings, in graphic novels, comics and even on cereal packets. This volume includes a series of visual essays on many of the film versions and also visual material for stage adaptations, magazines, playbills, book publications and even political cartoons.

Arguably the first ever science-fiction story, Frankenstein, as Frayling observes, “was a new kind of literary fiction, one which fused serious philosophical musings with an exciting story.” The novel was borne of Mary Shelley’s interest in vitalism, galvanism, occultism and other scientific debates captivating London’s scientific community at that time. The doctor was likely named for the castle where alchemist Johann Konrad Dippel allegedly experimented with reanimation using stolen corpses. Godwin’s mother, renowned feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, had also been resuscitated against her will after a suicide attempt.

When it was first released, Shelley’s novel received largely favourable but mixed reviews—one contemporary described it as “perhaps, the foulest Toadstool that has yet sprung up from the reeking dunghill of the present time.” It was not until it was adapted for the stage that it began to capture the popular imagination, inspiring several stage plays, a popular reprint of the novel and eventually screen adaptations. Victor and his creature are up there with Sherlock Holmes and Dracula as the most-filmed literary characters: over ninety direct adaptations, between 1931 and 2016’s Victor Frankenstein, and literally hundreds of others involving mad scientists, creations and nasty consequences.

James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) was a huge box-office hit, and it opened the floodgates. The ‘F’ word, the Franken-label, was from now on well and truly established as a badge to be attached by the press to any questionable scientific discovery. The ‘F’ word had become a brand, a name on the tin. From a Regency nightmare, Frankenstein has even become a cuddly childhood companion—thoroughly munstered, so to speak. The real creation myth of modern times—the era of genetic engineering, three- parent babies, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, robotics and singularity, human/animal interfaces and secularism—is no longer Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The real creation myth is Frankenstein.

Christopher Frayling is a recognised authority on Gothic fiction and horror movies. His study of Vampyres (1978, 1990, 2016), and his classic four-part television series Nightmare: The Birth of Horror (1996) have helped to move Gothic horror from margin to mainstream. His interest was sparked by watching Hammer Films in the late 1950s, when he was far too young . . . a misspent youth. Christopher is an award-winning broadcaster and writer. He was Rector of London’s Royal College of Art from 1996 to 2009, the world’s only entirely postgraduate university of art and design, and was also Chairman of the Arts Council of England. He was Professor of Cultural History at the RCA for over 30 years and is now Professor Emeritus. Christopher was knighted in the year 2000 for ‘services to art and design education’.