London Film Festival Review: Michael Haneke’s Happy End – “Fills us with voyeuristic guilt”

Sometimes it is necessary to read other reviews prior to writing one. The fear of accidental plagiarism is overruled by the desire to know, understand and further explain what has just been seen.

This practice is commonplace with Michael Haneke’s work. Filmmaker and master puzzler, his canon demands repeat viewing. These are films that are dense, complex and at times, shocking.

Happy End is a worthy addition to Haneke’s body of work. It is a comic thriller, a masterwork that delivers thrills long after the credits have rolled. So, this review is but an opening discussion and probable misinterpretation of the grievances and desires overlaid on Haneke’s ambiguous canvas. Long after writing this, another puzzle piece will click into place. His work is what cinema was made for.

Happy End concerns a family. They live in Calais, run the family construction business, eat around the family dinner table, and converse cordially, all while hiding psychopathic tendencies. In true Haneke style, what hasn’t been said is summarised from alternative perspectives: Snapchat posts that hint at crime, security cameras impassively recording an accident, snatches of sweet nothings murmured into mobile phones, until, slowly, the horrifying picture reveals itself.

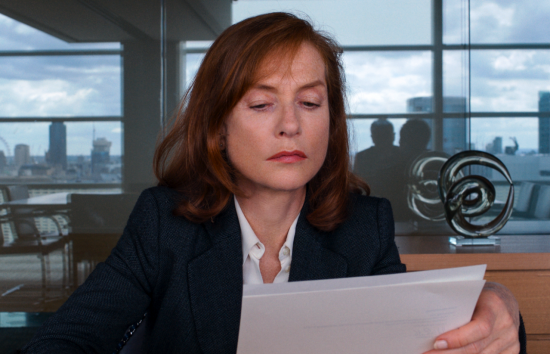

Jean-Louis Trintignant, is George Laurent, reprising his role from Amour as Pater Familiar to two children, Anne (Isabelle Huppert), business CEO, and doctor Thomas (Matthieu Kassovitz – a long way away from Amelie). When Thomas’s ex-wife is taken to hospital after a suspected overdose, their daughter Eve (Fantine Harduin) must stay with her father and his new wife and child at George’s country home. None of the Laurents are happy. George is descending into suicidal dementia, Thomas’s frowned-upon desires are less hidden from Eve than he realises and Anne’s relationship with English financier Laurence (Toby Jones) blurs the lines between business and pleasure. Perhaps it is Anne’s son Pierre (Franz Rogowski) who best captures the viewers’ perspective. In clear emotional distress throughout, he is trapped in a wealthy family that closes its eyes to the plights of its servants and of the surrounding refugees. Within this fascinating mess, Eve’s screwy worldview stands out as the most saddening and dangerous, as the plot loosely threads itself around issues of moral responsibility.

Happy End terrorises all who thought that the Oscar-winning Amour was about two loving souls together until the end. Haneke mocks us with a ‘Ha! Those happy souls produced evil offspring and the end isn’t even close!’

The master at work.

To attempt to neatly draw conclusions as to the film’s message would defeat the object, but it’s fair to say that Happy End is about modern cultural desensitisation. These characters are detached from morality, and a veneer of cultural respectability (read: money) renders them above the law. Haneke compounds their lack of sensitivity with a nonchalant, impassive direction of outrageous behaviour. At first demanding that the viewer judge, then, using detached tracking shots providing a distance and therefore a distrust of what has been seen. The Laurents are desensitised to violence, to mental illness, to poverty, to love, to emotional connection, and to the issues affecting other groups in society, who are clearly treated as lesser citizens, all deduced from scenes where the viewer cannot hear what has been said.

And of course, Haneke doesn’t let the viewer off of the hook either. The audience is voyeur, ourselves desensitised to the fact that cinema is a truth-teller not just happy fiction. The presentation of small moments of charity almost normalises the family’s antics, again chastising the viewer for being taken in.

Haneke is now seventy five years of age, with a better eye on the current world than others younger. The use of Snapchat live videos, Eve’s communication medium of choice, brings the movie right up to date and makes her disposition clear from the start (watch that hamster closely). And who is watching those videos? We are.

Haneke is now seventy five years of age, with a better eye on the current world than others younger. The use of Snapchat live videos, Eve’s communication medium of choice, brings the movie right up to date and makes her disposition clear from the start (watch that hamster closely). And who is watching those videos? We are.

But that’s not all. The cleverest touch of all is that Happy End demonstrates how easy it is to ignore the European migrant crisis, even in the work itself.

Some may say that Happy End isn’t Haneke’s best work, because it hones a developed style, barely delivering shocking pain until the very end. And yet, it may well be his greatest endeavour. Haneke dares us to stop watching, and then when we can’t, fills us with voyeuristic guilt. The Laurents are merely stooges for us all, in the midst of a global crisis. To reach a Happy End is to open our eyes to suffering outside of our own inner circles. Happy End delivers so much, the least that we could do is learn from it.