If you like Symbolism you’ll love The Red Turtle

Lost-at-sea movies have undergone a recent surge in popularity. Perhaps disposable incomes and mobiles, guaranteeing all whims catered for with the push of an App, breed a need for escapism? And there’s nothing quite so escapist as being shipwrecked on a desert island with only sand crabs for company.

Alternatively, viewers (myself included) fearing a future full of flabby layabouts are searching for further cinematic shocks to the system.

Then there are the Studio Ghibli aficionados, holding childlike wonder for cartoons well in to adulthood, who simply crave their next fix.

The good news is that The Red Turtle caters to all.

Although The Red Turtle marks the studio’s first worldwide co-production (seven producers and counting), it retains a universal feel, with plenty of Ghibli markers present. Symbolism threads through the narrative, and it is much more heavy-handed than is usual for the Ghibli canon. It’s easily done when The Red Turtle contains no discernible speech. Even Jay Bayona’s wonderful All is Lost gave us Robert Redford’s satisfying token shout, but Hayao Miyasaki would never be so uncouth. The Red Turtle therefore must tell its story through actions alone.

To give more than a vague explanation of the plot would spoil things, but I will say that this movie owes more to Terrence Malick’s catalogue than it does to Spirited Away. The Red Turtle shoves viewers into its world from the get-go. A man flails, close to drowning in very high seas. He tries to make it back to his capsized boat, the first of many bad decisions and fruitless pursuits. We follow this lost soul as he washes up on a deserted island and then the real story, in which this man does indeed meet a large red turtle, begins.

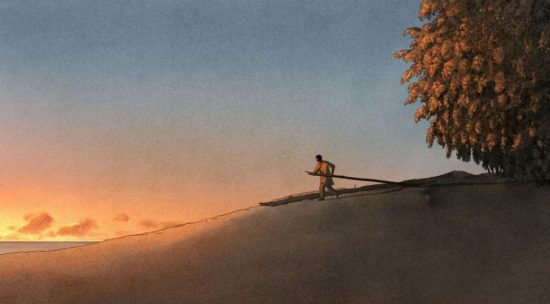

The Red Turtle borrows from Life of Pi in depicting man’s losing battle against nature, but this is only one of many philosophical questions explored. It is a visual spectacle. The animation is a force in itself, a riot of colour, which rivets on the big screen, combining beautifully with the music and sounds. I was affected, almost metaphysically, by crashing tides and wind-whistling bamboo forests.

The Red Turtle borrows from Life of Pi in depicting man’s losing battle against nature, but this is only one of many philosophical questions explored. It is a visual spectacle. The animation is a force in itself, a riot of colour, which rivets on the big screen, combining beautifully with the music and sounds. I was affected, almost metaphysically, by crashing tides and wind-whistling bamboo forests.

It is also undeniably tense. Some of the circumstances that befall the man (e.g. falling down a crevasse that he must escape from by squeezing through an underwater channel) are more stressful than I was prepared for.

Michael Dudok de Wit (Oscar winner for Fathers and Daughters) has easily stretched his directorial skills to feature-length work (80 minutes) with animation that’s deceptively simplistic. The human figures (intended to act as everyman guide through a morality tale) are drawn in an irritating bland form, and yet they still exhibit a complexity of movement not found in The Fate of the Furious. Dudok de Wit also retains the dappled watercolour backdrop synonymous with Ghibli work.

However, The Red Turtle is unusual in that it demands a great deal from viewers, requiring them to map their own experiences on to the plot. I felt tricked by a narrative which encourages the recognition of the difference between dreamscape and reality, before immediately turning this on its head. I couldn’t just roll with the tide, I had to create my own sense of truth. Some may like this, but I would have preferred a director more confident in delivering at least one of his messages.

And as with other Ghibli films, it will likely disturb adults more than children, who can see the dangers ahead. Thank goodness that these dangers are interspersed with scenes full of sweet humour.

In the end, I let my qualms go and focussed only on experiencing The Red Turtle in the moment. It is an emotional onslaught of terror, consternation and abject delight that I am not sure I fully understood, but its poignancy continues to ripple my subconscious.

The Red Turtle opens in the UK on 26th May 2017.