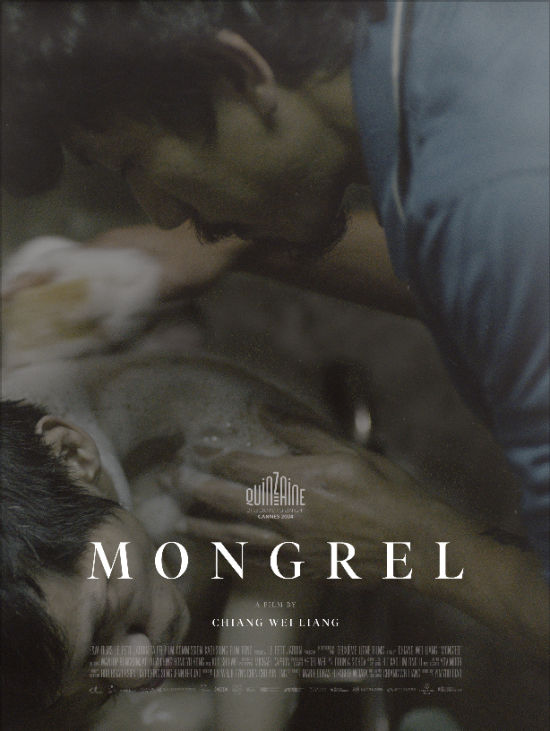

Edinburgh International Film Festival 2024 Review: Mongrel – “slowly effective and powerful”

Directed by Wei Liang Chiang and You Qiao Yin

Starring Atchara Suwan, Hong Yu-hong, Kuo Shu-wei, Lu Yi-ching, Wanlop Rungkumjad

This Taiwanese film arrives at the Edinburgh Festival hot from the prestigious Director’s Fortnight at Cannes. Mongrel explores a subject which may be set in Taiwan, but sadly covers a subject which is all too common all around the globe: the trafficking and exploitation of undocumented migrant workers. In this case, the gangmasters are in the mountain areas of the country, and using their workers (more like serfs) as care-givers for families who need them, but perhaps can’t afford the official care services, so this black market operation steps in to fill a need (for a price).

As we first meet the group, they are angry at their boss, justifiably so, because they have been working hard for him for two months and seen not a single penny of the money they desperately need to earn to send back home to their families abroad. When not working illegally (and mostly unpaid) they are kept in a secure compound, the euphemistically titled “dormitory”. Being undocumented workers, they have nobody to appeal to for help – employment or safety legislation simply doesn’t cover them, and regardless, even if it did, they dare not go to anyone in authority, because they would be arrested and deported.

It’s a wretched, desperate situation of exploitation, and yet Oom (Wanlop Rungkumjad), although obviously not happy at his situation, retains his sense of compassion – he gets to know the people he has to take care of, especially an older lady and her seriously disabled son. He’s not just going through the motions, he does actually care, despite being forced into this servitude, he’s a good soul and does his best by them, while also trying to mediate between his fellow workers and the boss (who as we see is in turn under a higher boss in the gangs, all running people’s lives like a business).

The film itself is very unusual – there’s not a huge amount of dialogue, particularly not from leading man Oom. Oom keeps most of his thoughts and feelings within, only small changes in expression and body language giving us a clue to what he is feeling; it is telling, perhaps, that the most I heard him speak was to the body of a deceased member of his group. The style too is unusual – some scenes go on for what feels like far too long (right from the start – the first scene is Oom having to clean the mess from a bed-ridden client, and the camera stays fixed on the scene for quite some time) until it starts to feel very uncomfortable. The shots are often very static, not moving with the characters but the camera remaining in place as a scene acts out around it, or at other times leaves a character looking directly into the lens, normally a no-no for most film-makers.

And yes, this does create quite a strange feeling – as I said it is uncomfortable, but the more I watched, the more I thought that was exactly the idea, because we should be uncomfortable at these scenes, while the often static choices of camera work make us feel like we are watching someone’s life, more like a documentary than a fictional tale, but where we have a fixed viewpoint that we cannot look away from. Having characters occasionally look directly at the lens reinforces this, especially one scene where the disabled man seems to be looking right at the viewers.

This really will not be for everyone – it is slow, it does not build up the traditional narrative (backstory, main story, character arcs), and deliberately uses camera techniques that also give the viewer a strange and not always pleasant feeling. And yet, if you stick with it, this is a slowly effective and powerful way of highlighting this modern story of international exploitation, more effectively than a more heavy-handed drama might.