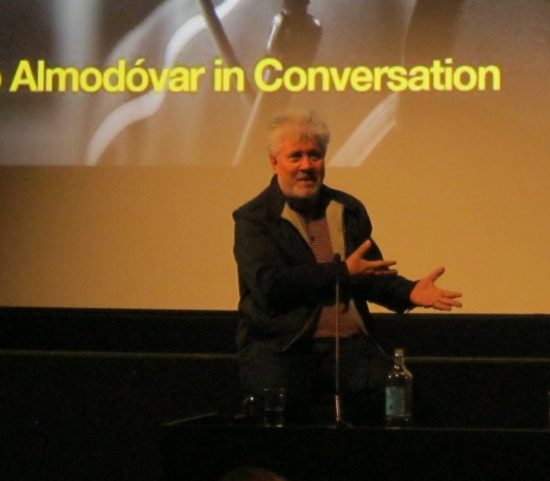

Pedro Almodóvar in Conversation at the BFI, Part Two

In part one of Pedro Almodóvar in conversation at the BFI, London, the Spanish director/writer discussed his obsession with colour and how much his new film, Julieta, changed between the idea stage and the shooting of it. In the second part, Almodóvar talks about actress Chus Lampreave, his brother, Agustín, and his upbringing in post Civil War Spain.

After showing a short, very funny clip of family bickering from La flor de mi secreto, Almodóvar was asked about actress Chus Lampreave, who passed away earlier in the year. ‘I feel the loss of Chus very greatly. It was very unexpected. I still haven’t got my head around the idea that she’s no longer with us. Chus had a great sense of humour. She wasn’t from La Mancha but she captured it… she spoke like my mother.’ He also said that most of the time, she was acting the character of his own mother.

Focusing on this particular scene from the film, Almodóvar confessed that it was filmed in a very peculiar way. He explains: ‘This is a reflection of the arguments between my mother and sisters. They adored each other but the impression they gave to the outside world was that they couldn’t hate each other more. We went to rehearse this scene at my sister’s house when my mother was then living. My mother and sister were sitting on one side of the room and on the other side of the room I was there rehearsing with the three actresses. Never have I felt like I did then, as if I were looking at a mirror and on one side was reality and the other was fiction, fiction that was reflecting that reality. Reality and fiction, at times, interacted. My mother and sister didn’t get offended listening to these barbaric comments that reflected what they had been saying to each other. My mother would actually take notes and give Chus comments and I was adding.’

On his brother, Agustín, Almodóvar says: ‘He’s my producer, fortunately. He’s my sign of identity.’

The audience was then surprised to learn that Agustín was there in the audience and he stood to great applause. ‘Agustín is the most important person in my life, and my work,’ Almodóvar continues. ‘He represents, for me, my memory . . . He’s a very strong person. I remember him in all the more important moments of my life and he was looking [at what was happening] with me . . . We have the same sense of humour. No one like Agustín understands what I write so I consult him since the very beginning and he also gave me a lot of great ideas . . . It’s a privilege. I’m such a free director because he takes care of that. He’s more conscious about the problems surrounding me.’

‘Having Agustín as a producer means that he has power over the film, especially when it’s released,’ he says. ‘The career of a film, its longevity, depends on the distribution and that’s not always dependent on the money you make.’ He continued that Agustín’s goal is to protect Almodóvar’s films, restore the negatives and sound in order to ensure, in the long-term, that they ‘shine better than ever’. He went on to say that ‘films are very delicate and if you don’t take care of them, they’re destined to disappear’. Almodóvar then added a heartfelt acknowledgement of just how lucky he is to have his brother by his side.

Fans of both Almodóvar himself and his work will no doubt be familiar with the massive influence his mother has had on him, in both his life and films. When asked about his mother, Almodóvar clarified that when he referred to his ‘mother’ what he actually meant was the entire community of women who basically raised him and his siblings. ‘This was a post Civil War generation,’ he says. ‘They were really strong women, fighters . . . they worked on the land and then they’d run the home and still had a sense of humour. They would wash things at the river and still sing songs. The country survived because of that amazing generation of women.’

There was no such thing as ‘nannies’, either, he explains, so you’d either go with your mother or stay with a neighbour. The men appeared at some time in the evening. They were symbols. The women sat on the patios, sewed, worked, and told stories, often about horrible things that had happened: suicides, unwanted pregnancies… Even aged four of five, the children heard these stories and Almodóvar credits much of who he is now and how he crafts his films (like Volver) to that time spent on those patios, hearing these stories.

Going back to his fascination with colour, Almodóvar noted that his mother and people from his generation generally dressed in blacks and greys. He remembered the time, whilst he was working on Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, that his mother spoke to the stylist and said ‘Bring me flowers. I don’t want black’. Almodóvar overheard her tell the stylist that, since her infancy, she had been made to wear black because of the death of her parents. Then, as more family members passed away, she had to continue wearing black. Until she was thirty, she basically lived in black clothing. Almodóvar was shocked by this revelation and thought that he was the response to that tradition – with the vibrancy of the colours he was going to employ.

He then clarified: ‘Black is a very elegant colour if you decide to wear it. If you don’t decide to wear it and it’s inflicted on you then it’s a nightmare of a colour.’

When it came to opening out the questions to the audience, a certain Almodóvar-esque farce ensued. One audience member, who’d come all the way from Venezuela, asked if Almodóvar could sign his Kika poster. After getting over his surprise, Almodóvar agreed, basically because the guy had come so far that he didn’t feel right refusing. The Venezuelan (and his poster) then came to the stage at the same time as another audience member began to ask his question, which was about Almodóvar’s use of sex in his films. The man asking the question soon realised how distracted Almodóvar was in that moment and so waited for him to finish signing the poster before continuing. When the Venezuelan (and his newly-signed poster) had returned to his seat, Almodóvar looked out into the audience and asked ‘So. What do you want to know about sex?’ The question was so good and so beautifully illustrated Almodóvar’s incredible wit and humour that it was almost irrelevant what his actual answer was, but here goes:

‘Sex is part of life and part of the life of the characters. I don’t try to show organs but instead create the illusion that what you’re seeing is real. Fortunately, I have worked with actors without prejudices and problems in this area and they’re largely responsible for why these scenes have come out so well.’

In Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, Almodóvar explained that the Motion Picture Association of America decided to class the film as X-rated because of the sex scene. It was a close-up, he says, and the camera was moving with them. For the MPAA viewers, they thought it was real and that it was basically a porn film. ‘It’s not censorship in the sense that they say “cut this”,’ he continued. ‘No, they give you the scissors.’

So, on to his next project. Well, what might be coming up next for Almodóvar is anybody’s guess. He’s currently working on three scripts: a dark comedy, a thriller and a ‘sad story’. So, only time will tell which route he chooses. Whatever happens though, Almodóvar promises ‘I will keep on making movies’ and we’re delighted to hear it!

Julieta is out in UK cinemas on Friday 26th August.