A Writers On Film Essay: Paul Newman and the Hollywood Memoir

The arrival of Paul Newman’s memoir The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man prompted a double take. How had I missed this? Paul Newman is one of my favourite actors; and yet I’d never heard of this memoir until now. But it soon became apparent this was a new book, a posthumous editing together of a series of interviews that the actor had conducted with his friend Stewart Stern between the years of 1986 and 1991. The project hadn’t faltered: it had in fact been long abandoned. Newman would die in 2008 and Stern himself in 2015. There had been thousands of pages of transcripts; hours of interviews. This was the raw material that has been edited down and salted with quotes and comments from a variety of sources. It ties in also with Ethan Hawke’s documentary The Last Movie Stars (2022), which portrays the marriage between Joanne Woodward and Newman and yearns for the glamour of times long gone.

The arrival of Paul Newman’s memoir The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man prompted a double take. How had I missed this? Paul Newman is one of my favourite actors; and yet I’d never heard of this memoir until now. But it soon became apparent this was a new book, a posthumous editing together of a series of interviews that the actor had conducted with his friend Stewart Stern between the years of 1986 and 1991. The project hadn’t faltered: it had in fact been long abandoned. Newman would die in 2008 and Stern himself in 2015. There had been thousands of pages of transcripts; hours of interviews. This was the raw material that has been edited down and salted with quotes and comments from a variety of sources. It ties in also with Ethan Hawke’s documentary The Last Movie Stars (2022), which portrays the marriage between Joanne Woodward and Newman and yearns for the glamour of times long gone.

I have no problem with publishing material posthumously, nor marketing it as a memoir though the reshaping that has gone on has a significant authorial impact. In this particular case, this is partly because of the quality of the book. Paul Newman speaks with a rawness in a self-lacerating confession. His voice is that of a man breaking his silence, getting things off his chest. It is spiky and bitter, ironic and sharp, intelligent and unrelentingly self-critical. It is not all revealing. Neither is it exhaustive. Whole chunks of his career are missing. And some of the material you might expect is covered only glancingly. It is partial in more ways than one.

Our relationships with stars depend very much on how we meet them. As a kid, I met Newman as an already established fact. He was Butch Cassidy, the con man from The Sting (1973). He wasn’t as legendary as Humphrey Bogart, in that he was still alive. And whereas Bogart was only ever one age – middle – Newman had a whole trajectory to him. He aged before our eyes, most notably as Eddie Felson from The Hustler (1961) to The Color of Money (1986). But with the grey hair and those eyes, he was both preternaturally young and never really young at all. Older than his years.

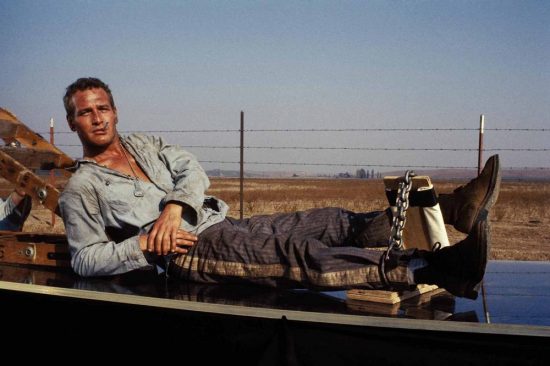

And he was cool. But not in a Steve McQueen way. The two would clash in The Towering Inferno (1974), with Newman’s architect laying claim to his authority ‘It’s my building’ leading to McQueen’s fireman one-upping him ‘But it’s my fire.’ But that cool – that beauty – never rested on itself: was never a comfortable, at ease coolness. It looked less like languor than exhaustion; less like indifference than surrender. Newman’s smile always hinted at imminent disappointment, his anger simmered below the surface. His roles spurned sympathy, spurned adoration. He didn’t do heroes. He’d always prefer to be the guilty architect than the triumphant fire chief.

Look if you like at Hud (1963) – taken from Larry McMurtry’s novel Horseman Pass By – in which he plays a photogenically perfect Texan rancher, whose devil-may-care attitude doesn’t stop at rape. In the Donn Pearce’s novel which became Cool Hand Luke (1967), the main character also commits rape. In Sweet Bird of Youth, he’s a male prostitute attempting to blackmail an aging actor into giving him a break in Hollywood. In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the repressed homosexual subplot is more present than if they’d just come clean about it. In all these films, there is the courage of an actor who isn’t framing an image or protecting himself against controversy. Looking as he did – a ‘decoration’ as he calls himself repeatedly in his memoir – he could afford to bounce off this, much more so than Robert Redford who appears always to be more tentative and careful that his characters reflect well on him. Newman’s heroes might be obnoxious, or dumb; vainglorious or deceitful. His ambulance chasing lawyer in Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict (1982) wasn’t an iconoclastic stretch for Newman. Many of his most memorable roles were determinably flawed, buoyed up by the glamour he brought and daring us to like them regardless of what they were doing on screen. They were a repeated experiment in the Halo Effect of his beauty: how much would we let him get away with because he was Paul Newman.

That this was in some way rooted in his life is evident in his memoir. His honesty is revelatory. He is dismissive of his art: never enjoying acting, rarely believing himself to be any good. He is ambitious and driven, but ultimately sceptical, assuming that his fame comes from the same place as his mother’s fickle adoration of him as an ‘ornament’. He treats people around him badly including his first wife Jackie Witte, who he marries impetuously and then cheats on throughout their relationship. He’s an alcoholic, whose drinking is dangerous. The death of his son Scott haunts him and he finds it difficult to live with the guilt, relentlessly asking what else he could have done, while acknowledging equally guiltily that maybe he would never have done – i.e. relinquish his career – if that’s what it took. His relationship with Woodward is more complicated than the image suggests, with further betrayals hinted at but not fully revealed. As an actor, Newman explains that he has always felt cut off from emotion. He uses tricks – staring at a light to make his eyes water for tears – and feels out of place at the Actor’s Studio. His discomfort with fame leads him to an abrasive relationship with the public, in one anecdote upbraiding a woman in a restaurant for joining his table as ‘the rudest fucking woman I’ve ever met’. Even his charity work doesn’t escape examination. He questions his motives and dismisses any sense of sacrifice involved. He could give millions away and still have millions, he not unreasonably concludes.

Ultimately, there is a pervading sense of sadness. Newman appears as a man constantly striving and impatient; capable of great affection and love, but unable to stand still and receive it. I once talked to James Ivory about Newman. Ivory directed both Woodward and Newman in Mr and Mrs Bridge (1990). Far from age mellowing him into some On Golden Pond style relic of halcyon days, the film has Newman once more playing another deeply flawed and abusive character. Ivory told me that they had it written into the contract that Newman couldn’t go car racing in his downtime as the insurance was too expensive. But every Monday he’d show up to set with sunburn and the make-up artists would have to do their best to conceal the peeling red of his nose: ‘He was naughty. … It was part of his personality. You couldn’t talk him out of it.’ The car racing always felt similar to McQueen’s; it felt like a reaction towards the shame many men of their generation felt about acting: ‘no profession for a grown up man.’ It was an opportunity to display their masculinity, their physical courage. Something Tom Cruise is still tooling around doing. But – not to reduce everything to glib psychoanalysis – it was also something he enjoyed very much in and of itself. While we were all wishing to be Paul Newman, Newman himself in his moments of purest pleasure could forget who he was.

John Bleasdale is a writer and critic; and the host of the Writers on Film Podcast.

First published on Substack.