Social Discord Burns Brightly for Mehdi Firki in After the Fire

Trevor Hogg sits down with French filmmaker Mehdi Firki on a café patio in Toronto to discuss the creative, technical and societal challenges in making After the Fire…

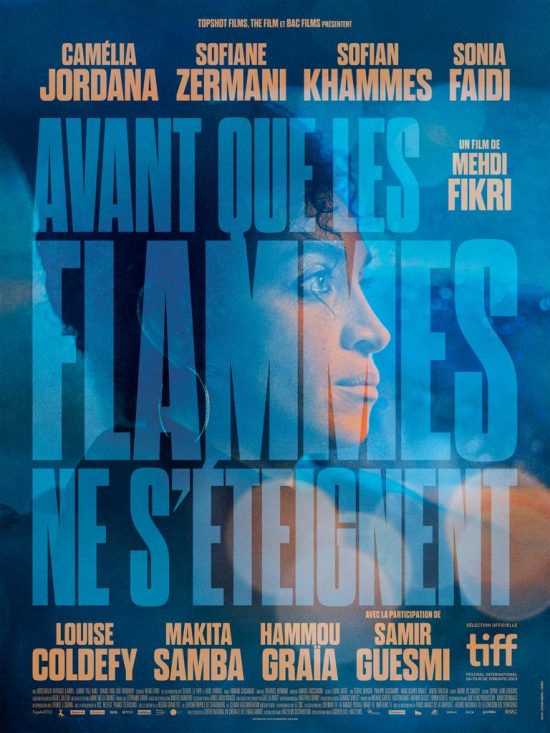

Ethnic turmoil has sadly become part of the social fabric of France with police brutality becoming a flashpoint for accusations of institutional racism. Inspired by his decade of covering the social unrest in the working class-suburbs of his hometown of Paris, Mehdi Firki made his feature director debut After the Fire which had its World Premiere at the 48th Toronto International Film Festival as part of the Discovery Programme. The story revolves a family of North African descent living in Strasbourg having to deal with the death of one of their own while in police custody and seeking justice from the French legal system. Surrealism defines the opening shot which is reversed slow-motion footage of a burning car. “You liked it?” asks Mehdi Firki. “When you film fire, it blows your mind. To me it’s like water. We burned this car and started shooting it. The image is slowed four times so its 124 frames per second and that creates this crazy effect. It’s almost magical. I was like, ‘Lets go for it.’ It’s interesting because I always had the idea for this reverse shot but I didn’t put too much meaning in it. This shot moved in the screenplay to different places. During the editing it became clear to me that the shot had to be at the beginning.”

Mehdi Firki. Photo Credit: Norman Wong.

There are some clever cinematic moments such as when Malika El Yardi (Camélia Jordana) is standing outside the hospital and sees a slight gesture from within the building communicating that her brother Karim El Yadari (Abdelmalik Yahyaoui) has died and in turn causes a peaceful protest to become a riot. Another is an aerial shot of the protests that settles upon circular playground and dissolves to the top of candle burning at a wake being held at the parent’s apartment. “Thanks so much that you’ve seen that!” states Fikri. “I’m really happy! I didn’t do a storyboard. What I did for that shot is I used Google Maps to figure out an aerial shot for the drone and saw this place which gave me the idea for the shot.” The fires from the protests were added in digitally. “The visual effects budget was small. The aerial shot is packed with CGI. We also have CGI in the tracking shot for the wake. There is the smoke and police car moving in the background which is CGI. I chose my CGI battles which were very few and we put all of the money into them.” Time was at a premium during preproduction. “What I learned from this movie is you prep a lot in order to be ready for the unexpected. Plus, because we were short of money and I am based in Paris but we were shooting outside of Paris so I didn’t have time to be onset. Also, we were changing sets a lot so I had a lot of ideas and was using some of them according to the location. I already had the idea that it should be a long tracking shot for when you follow Malika from the apartment [down the stairway] so we chose the location according to it.”

Getting permits for locations was complicated by the film being highly critical of French law enforcement and the legal system. “Yeah, it was hard,” admits Fikri. “I was talking about having a point of view but the guys didn’t say this but if I put a nice white saviour or policeman, it would have been easier for me to get authorization. The riot scene was shot in part of the city where we’ve got the conservative mayor and he said, ‘I’m going to send you the city police.’ We had to shoot it between 6 pm and midnight. We had six hours to shoot all of this. It was crazy. Also, we needed to shoot inside of the courts of Strasbourg. There was a cool woman from the ministry who read the screenplay and said, ‘Yes. Go shoot your movie.’ But the main prosecutor, basically the boss of the Strasbourg Court is conservative and said, ‘Fuck this. I’m not going to be shooting this in my court.’ We had to shoot it in Colmar which is one hour outside of Paris. It was one of the reasons that we shot in Strasbourg because Strasbourg has a progressive elected people, progressive politics, Strasbourg and the surrounding area. It was easier but more difficult.”

Cellphone footage of Karim does not appear until the end of the movie. “I truly believe in point of view from a narrative perspective because it helped us to create an immersive story to be only with the sister,” explains Fikri. “I have to admit for the death of Karim when you only get the sound, I actually shot the scene. I had to reassure my producer who went, ‘Do you really want to do that without the image?’ I was sure. We are with Malika. She didn’t see her brother die. This is her story. It is important. That’s why we don’t see so much of policemen. She saw them like the riot in the rearview window of the car.” It was critical for Malika to have a Caucasian sister-in-law portrayed by Louise Coldefy named Estelle. “Louise Coldefy is a comedian and she was so happy. She told me, ‘I want to do drama.’ She was so fond of the subject. Louise did a great job. Also, it was important to me to show interracial couples because I come from an interracial family. My mother is white and in France we’re not coming from a story of segregation. There are lot of interracial couples. We have white people inside of our family so it was important for me to show that.”

Actual archival footage is saved for conclusion of the story to emphasize that it is based on reality. “I’m a huge fan of Spike Lee,” remarks Fikri. “He’s doing a political movie with the fine mise en scène at the end of Malcolm X. Spike Lee doesn’t give a fuck. You see Ossie Davis and Nelson Mandela. Also, at the end of BlacKkKlansman, you got pictures of Charlottesville. It was the year before and you see the whole fucking attack of the fascists inside of the protest. Archival footage gives me shivers all of the time. I want to cry and maybe it’s because I’m a former journalist. When I was on the sixth and last week of shooting, I said, ‘We’ve got everything in the box but I need archival footage.’ I was so fucking sure.” Fikri does not foresee a bleak future. “I want to give a feeling of hope because we have this media cliché that everything is lost and is going end in a massive bloody showdown with the policemen fighting against Black and Arab people. I wanted to show that there is hope in politics. My parents were political activists and lost all of the battles of the 1980s and 1990s; they are a bit bitter like the activist Miguel Lapierre. We live in a sad world but I do not totally agree with that. Politics give us meaning and brothership beyond race and social class. Also, the music and archival footage at the end was a way to cheer up. It was my idea to finish with a sense of hope. Maybe we will have our Donald Trump at some point but I believe in the younger generation and in the fact that we can together build a good future.”

Special thanks to Mehdi Firki for taking the time to be interviewed. For more information visit the official website for After the Fire.

Trevor Hogg is a freelance video editor and writer who currently resides in Canada; he can be found at LinkedIn.