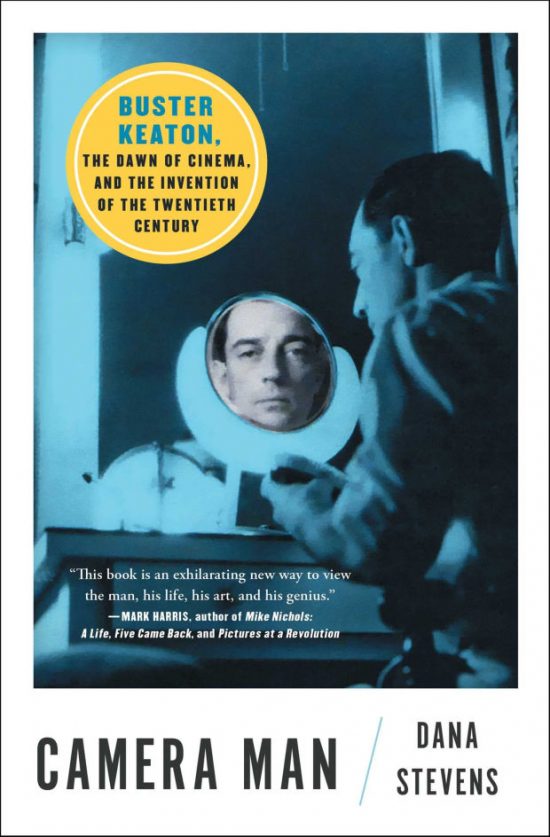

Book Review – Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century

“I count the years of defeat and grief and disappointment, and their percentage is so minute that is continually surprises and delights me.”

I’ve adored Buster Keaton for as long as I can remember; when I was very young, the films of Buster, Harold Lloyd, Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy were a staple on television, often put on during the school holidays, and were the gateway into that long-ago era of early film for me (and for many others, I would think). I watched them with my dad (who would delight in telling me how he actually saw Laurel and Hardy when he was young, his father taking him to see them on their final UK tour – clearly love of this kind of humour runs in our family). Actually, we still watch them together to this day, enjoying them as much, if not more, than we did when I was just a little boy. I imagine this is a scenario more than a few of you will recognise and likely share – not just watching these films and loving them, but sharing them with someone important to you (which always makes them better and even more special).

I’ve adored Buster Keaton for as long as I can remember; when I was very young, the films of Buster, Harold Lloyd, Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy were a staple on television, often put on during the school holidays, and were the gateway into that long-ago era of early film for me (and for many others, I would think). I watched them with my dad (who would delight in telling me how he actually saw Laurel and Hardy when he was young, his father taking him to see them on their final UK tour – clearly love of this kind of humour runs in our family). Actually, we still watch them together to this day, enjoying them as much, if not more, than we did when I was just a little boy. I imagine this is a scenario more than a few of you will recognise and likely share – not just watching these films and loving them, but sharing them with someone important to you (which always makes them better and even more special).

So, as you may guess, I was more than delighted to be sent a copy of Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century by Dana Stevens, film critic at Slate and also a lifelong admirer of Keaton’s work. I was even more delighted to find this is far more than a biography; yes, it does, as you would expect, contain a lot of biographic information, from Buster’s early days as a child star on the vaudeville stages with his family, performing unbelievable – not to mention dangerous – acts and stunts (that would stand him in such good stead when he moved to film), through early exposure to film work, finding his feet in the new medium, the changes as the years pass, the downs as well as the ups, his later life.

Yes, that’s all here, and it is fascinating. However, Stevens also does something far more interesting – she discusses what is going on around Buster as his life and career unfolds across the decades, in popular culture, society and in technology. This means not only taking in aspects of Buster’s world you might expect, such as how the new-fangled moving image (born in the same year as our man, 1895) would start to encroach on the older forms of popular entertainment, such as the vaudeville circuit Buster’s family operated on, or how the introduction of sound, or the emergence of the large studio systems, replacing the many small, independent, seat of the pants production companies, and how this affected Buster, determined his choices and options.

But it also takes in the wider world around him – we see an early American movie industry where many women held senior positions such as producers and directors, as well as being on-screen talent (sadly something that changed to the still too familiar patriarchal system with the coming of the big studios), we see early experiments in a totally new medium, artists figuring out what they can do with this flickering image, pushing what can be done on film. We also see the wider world around it – the “new woman” of the 1910s and 20s, the multiple connections across all levels of society (one early film critic, a great supporter of Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton’s art, would also become a speech writer for Franklin D Roosevelt), we see the emergence of that gloriously hedonistic 1920s Hollywood (so recently celebrated in the film Babylon), where a newly flush Buster buys a big home, with near neighbours like Valentino, and Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks (whose Hollywood mansion boasted a lawn so big the Goodyear Blimp could land on it!). Changes in gender relations, race relations and more as society alters and changes, it’s all in here.

But it also takes in the wider world around him – we see an early American movie industry where many women held senior positions such as producers and directors, as well as being on-screen talent (sadly something that changed to the still too familiar patriarchal system with the coming of the big studios), we see early experiments in a totally new medium, artists figuring out what they can do with this flickering image, pushing what can be done on film. We also see the wider world around it – the “new woman” of the 1910s and 20s, the multiple connections across all levels of society (one early film critic, a great supporter of Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton’s art, would also become a speech writer for Franklin D Roosevelt), we see the emergence of that gloriously hedonistic 1920s Hollywood (so recently celebrated in the film Babylon), where a newly flush Buster buys a big home, with near neighbours like Valentino, and Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks (whose Hollywood mansion boasted a lawn so big the Goodyear Blimp could land on it!). Changes in gender relations, race relations and more as society alters and changes, it’s all in here.

It all serves very effectively not only to give an overview of Buster’s life, his craft and his body of work, it gives it all so much more context, placing it in the world he was in at each moment of that remarkable life, which is vitally important, because it’s all connected, it influences everything. Stevens doesn’t shy away from discussing aspects such as race – a common “minstrel” trope of the period, involving blackface and a parody of an African American that is very hard for a modern viewer to watch is discussed, for instance, while she also notes the shoddy treatment Mabel Normand, one of the biggest women in film of her time (and so sadly often overlooked today) received (Keaton’s contemporary, Chaplin, was especially singled out for his chauvinistic stance to taking orders from a women director, despite her having far more experience than he has, just starting out in film). And, of course, it explores the darker moments – the marriage failures, the terrible time lost to alcohol abuse.

However, the main focus here is clearly in celebrating one of the most remarkable figures of early cinema, and rightly justifying why he is important, not just specifically in the history of comedy, but also in film history in general, for his innovations and techniques, his eagerness to embrace new technologies and see what he could do with them, and, most importantly, how he could use them to create a good gag and make people laugh. And there is a lot of laughter to be had here, rather fittingly – it’s hard to read some descriptions of moments from making those films and not to start giggling away with laughter. Frankly, I sat there with a big smile on my face for a lot of this book, pausing now and then to put the book down and then go and watch some of those films (fortunately so many are available online now). In fact, I think this is a book that encourages you to stop reading periodically and go and watch some of the films it is discussing.

Kudos also to Stevens for using the latter segments of the book to bust (bad pun intended, sorry) some of the myths about Buster’s later life – many still think he made just a handful of films after sound came in, then spent the rest of his life in the shadows of his former reputation, drinking away. And while he did go through some very rough times and a long, dark night of the soul, that’s far from the full truth. Stevens takes us through the 1940s, 50s and 60s; we see Buster still writing, still performing, on stage (at a sadly now gone famous Parisian circus post-war, where he was rightly acclaimed as a great artist) and then getting himself involved in another emerging new medium – television.

Yes, Buster had his own show for a little while in the early days of TV broadcasting in the US, and he found a new outlet for new gags and pranks to delight a new audience. This new medium – whose emergence so frightened Hollywood at the time – would also be a major part of the reason his and other performers from that era had their reputation and place in film history cemented, because some of those old films were unearthed and shown on the new “boob tube”. In much the way it did with Universal’s famous monster movies of the 30s, so long out of fashion, the TV screenings made them new to a different audience – performers like Keaton, Chaplin, Lloyd, Lugosi, Karloff, they all had a renaissance in popular culture this way, and that’s never truly gone away. The book also touches on the first stirrings, decades on from the Silent Film era, to find and preserve that rapidly disintegrating treasure trove before more of it was lost for all time (for which I imagine many of us are profoundly grateful), along with a cultural reevaluation of the importance of those works. He was still working away on new ideas and projects pretty much until the end.

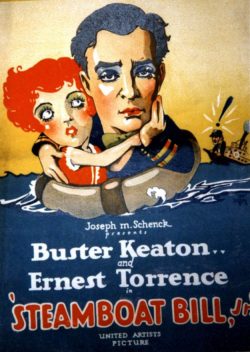

A few years ago I went to a Keaton screening at my beloved Filmhouse in Edinburgh (home to the Edinburgh International Film Festival – sadly closed suddenly last autumn, you can read my report on that sad news elsewhere on LFF). It was a weekend matinee, the cinema actively encouraged family groups with children (with very low ticket prices too). The screening was a bunch of Keaton shorts, then an interval, and the second half was the feature, Steamboat Bill Jr– yes, the one with the front of the house falling on Buster, who emerges unscathed through the window frame (this was all shot for real!). That was also his last independent feature; after this he was folded into the new studio system, working for MGM, who removed his artistic freedom and ruined what could have been good films (sadly a tale many artists in many a medium are too familiar with to the present day, the Suits telling the Talent what works).

A couple of rows in front of me was a man with his two wee boys, maybe around six and seven years of age. They laughed with their dad all through the endless gags of the short films. I found myself wondering how they would react to a feature-length silent movie in the second half; I needn’t have worried, the little boys sat spellbound at Buster’s athletic stunts and laughed and laughed. I include this little personal moment here because it illustrates something Stevens does so well with this book – Buster is as wonderful and funny to new audiences as he was in his 1920s silent-era heyday, and he’s always being discovered by someone for the first time, just as I first found them when I was a kid, watching with my dad, and here I saw that process taking place again. More importantly I got to sit in a cinema, watching a man long dead, restored to life by a magical, flickering beam of light, and that man-made people smile and laugh. What a wonderful gift and legacy.

Camera Man is published by Atria Books, out now in hardback, with the paperback release this April.