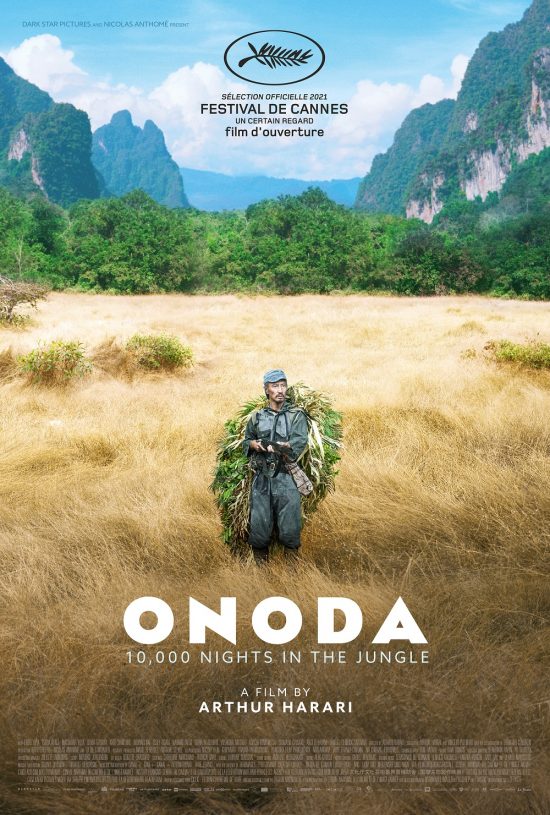

Review – Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle – “Worth the investment of viewing time”

Directed by Arthur Harari

Starring Yuya Endo, Kanji Tsuda, Yuya Matsuura, Tetsuya Chiba, Shinsuke Kato, Kai Inowaki, Issey Ogata, Taiga Nakano

“I forget none of you.”

There were several famous cases of Japanese soldiers who did not obey – or in some cases had simply not received – the surrender order in 1945, and carried on a lonely war for many years after the end of World War Two, in isolated regions. Hiroo Onoda, a second lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese forces, became one of the most famous after writing (or, it seems, more accurately, collaborating with a ghost writer) on his memoirs after he finally accepted the surrender order and was returned to Japan in 1974, after almost thirty years on the island of Lubang in the Philippines.

Director and co-writer Harari made clear in interviews that he is not working from those memoirs, and that the film is not a biopic, rather more a film inspired by real events and persons, but with him treating it as largely fictional. Given there is still controversy over the real Onoda’s accounts in his memoirs (reportedly he avoids mentioning killing several innocent locals during his three decade guerilla war), that seems like a fairly sensible approach, and it also allows the director and actors much more leeway in telling the story. As it spans almost three decades, some of the principal roles, such as that of Onoda himself, require two actors, one to play the younger version, and another for the much older, middle-aged version, with Yuya Endo and Kanji Tsuda respectively portraying the younger and older Onoda.

When we meet the young Onoda, the war is already moving into its final phases, with the Allied “island hopping” strategy taking them across the Pacific, winkling out the occupying Imperial Japanese forces in often grinding and bloody battles, then on to the next. The Onoda we meet here is already feeling shame at failing to become a pilot, and having been given a second chance as an officer with special training in secret warfare – he was schooled in holding out after an expected invasion, schooled not to commit suicide or die in a “banzai” charge (as most Japanese at the time would have been instructed to do), rather to melt into the jungle with a small group, establish safe bases and supply caches, then raid enemy forces and continue guerilla-style warfare until the main Japanese forces returned to relieve them.

This drives Onoda, he clearly feels he has something to prove – on top of the fact that, like most other Japanese soldiers of that era, he has had unquestioning discipline and loyalty to the Emperor drilled into him – and when the few men he has with him start to falter, he reveals his secret training and orders, which bolsters them into continuing the fight. However, soon the Allied forces have moved on, and the only fights they have are with unfortunate, and totally innocent civilians, local villagers and farmers, often when raiding for supplies. They have become bogie men, figures of fear on the island, and on hearing shouts that the war is over, they refuse to believe, assuming it is a trick.

As the months become years, however, it wears on the men, living rough in makeshift shelters in the jungles and hills, in rotting uniforms darned with numerous patches. Their numbers slowly reduce as some leave, while others are injured or killed, until we end up with Onoda and Kinshichi Kozuka (played by Yuya Matsuura as the younger soldier, Tetsuya Chiba as the older) for a substantial part of the running time. We see the pair reinforce one another’s delusional ideas as they come up with varying interpretations and reasons why articles in magazines and newspapers they’ve stolen are all fabricated (the “fake news” of their day, they think), even convincing each other that the broadcasts they hear on a purloined transistor radio are all designed to trick them into surrendering, and if the Allies are going to such lengths then it means their island is more strategically important than they realised, therefore they must carry on.

In a modern era where we see whole swathes of society willingly embrace fake facts (even when they have access to multiple sources to dispute misleading claims), it’s not hard to see how isolated characters, cut off from all they knew, their only information sources sporadic and not trusted, would build an elaborate fantasy around them to explain and justify their continuing the war for so long, to validate their narrow world view. Delusional? Quite possibly, however, Harari doesn’t depict him too strongly in this light, we also see the compulsion and drive to duty and orders which makes Onoda continue, year after year, even rejecting pleas from his own father and brother brought to Lubang to call for him on loudspeakers to come out.

The lengthy running time (barely shy of the three-hour mark), lets this run as a slow-burn tale, with flashbacks to his training, to his farewell to his father (his parting words and gift not an “I love you”, or “take care” but a ceremonial dagger for suicide and instructions not to be taken alive), and this also works in allowing us to feel a slight taste of the long, long years Onoda fought on as we get more time to get to know him, what shaped him to be this person who would hold on for twenty-nine years after the war’s end. We get to know the small – and ever-shrinking – group, and while the film does not (unlike the real Onoda’s biography)skirt around the fact they attacked and killed local people, we also feel for the men as we get to know them. Some later scenes are particularly emotional, as a much older Onoda, now all alone, visits the graves of his fallen comrades, the graves almost invisible now, hidden by jungle growth. He names each one and where they fell, and how he will not forget them and their shared comradeship, the only one who knows what happened to them, where their bones now lie.

It’s an interesting film – the length and slow-burn approach may put some off, but I found it worth the investment of viewing time, and particularly liked that Harari didn’t portray Onoda as either just a heroic – if deluded – figure, nor as a lunatic, victim of his own delusions and self-invented conspiracies, but allows a more nuanced interpretation where, like much in life, it’s a mixture of things. If you are looking for a fast-paced, war-action flick, this is not it, but if you are looking for something more cerebral, that examines motivations, male bonding under stress (some elements there made me think of Peckinpah, where the stoic, masculine heroes can only emotionally bond in certain dangerous situations); it would make a good book-end to Eastwood’s Letters From Iwo Jima.

Onoda won the 2022 César Award for Best Original Screenplay, and will be released to on-demand services by Dark Star Pictures from December 13th.