We Are The Music Makers and We Are The Dreamers of Dreams – an interview with Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe

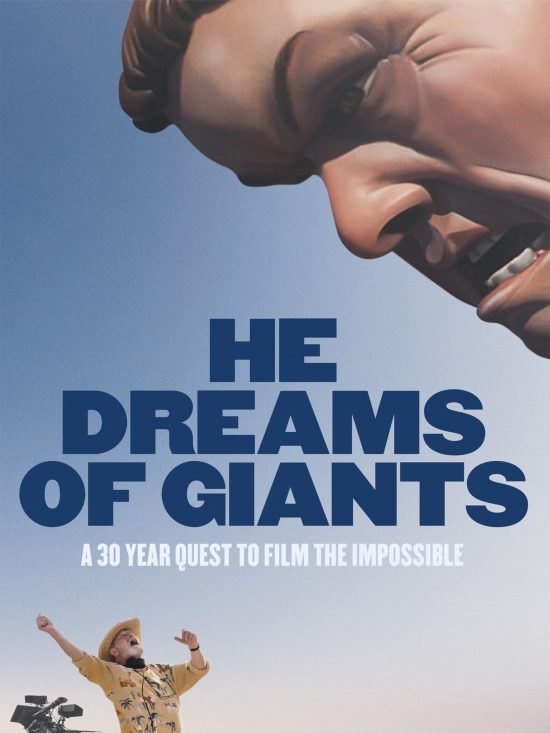

Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s new documentary caps off their “Gillogy” of films of Terry Gilliam, which includes The Hamster Factor, Lost in La Mancha and now, He Dreams of Giants. The documentarians have created a trio of films that are in some ways similar to the Michael Apted series 7 Up, except instead of looking at the lives of a group of people through the years, they cover different phases of director Terry Gilliam’s work and life, and the process of change and aging. He Dreams of Giants is a difficult film to watch, especially if you are a big fan of Gilliam. But a lot of what you love about his films comes out, even as you see various factors (including his own health issues) conspiring to sabotage his dreams.

He Dreams of Giants is released Monday for video rental on all the usual platforms.

Do you see He Dreams of Giants as the closing chapter of the continuing chronicle of Terry Gilliam’s films?

Louis: That’s definitely the final chapter.

Keith: You can’t do more than three, three is a magic number. This is a “Gillogy”—that’s what we’re calling it. We finished the Gillogy.

The making-of series reminds me of the 7 Up series, viewing Gilliam in three very different circumstances. What do you think of that analogy?

Louis: To some degree, yeah. I don’t know, it must’ve been a year and a half ago I actually had the good fortune to run into Michael Apted, rest his soul, at a party and got into a conversation on the process of coming back to the subject. There is draw in documentary, because you become intimate with a person when you make a film about them. They become very live characters in our imaginations. We want to revisit them, we want to know what the next chapter of the saga is. I think we definitely saw a connection there.

How did you first get in touch with Gilliam at the time you made The Hamster Factor?

Keith: We were graduate students in film at Temple University in Philadelphia, both Lou and I started that program in 1990. Gilliam and his crew came to Philadelphia to make 12 Monkeys. They shot that in Philadelphia and Baltimore, and Terry was looking for film students who would be interested in following him around on that production. As he said at the time, “we would hope he would have witnesses” in case he got into another battle with Universal. We interviewed with him and made a reel of our work at the time, and he was impressed—and we got the gig… well, “gig”… we didn’t get paid. We followed him around for the course of an entire year on 12 Monkeys, through production, post-production and marketing, the whole deal.

How was it waiting for that phone call this time saying “are you ready to start shooting the making-of”? Were there any false starts before you were going to start shooting Terry again?

Louis: Keith and I had just completed a documentary in 2016 called The Bad Kids, and we were actually travelling abroad. Terry’s daughter Amy got in touch with us, saying “the film is going in a few months, do you want to come and shoot?” It had been a long time since we had made Lost in La Mancha, and we were moving into a slightly different direction with our documentary work.

Keith: As in not on movie sets! Movie sets are the last place we want to make a documentary!

Louis: So it was a big decision: do we want to return to an older mode? Do we want to return to a pattern that is different from what we have evolved into? Then we said “yes”… and then Terry’s film didn’t get off the ground in 2016 as he thought it would be. Then they called again in 2017 and said “it’s going in six weeks,” and Keith got on a plane to start shooting, and I joined him not long after.

Did you feel an obligation that you had to do it at a certain point?

Keith: There was that component; there was a trilogy unfinished, for one thing. We had made two films about Terry, and that wasn’t the magic number. We also had a phone call with our colleague and friend Tony Grisoni, who wrote the script for Terry’s film The Man Who Killed Don Quixote and our movie Brothers of the Head as well. So Tony said, “how could you not do this? And close out this chapter?” He guilted us into doing it, it’s his fault!

Louis: Terry even said to us, “who else was I going to ask to shoot this?” it needed to be the same eyes that been here for what had become Lost in La Mancha. I don’t want to say it was a sense of “obligation” on a personal level but we felt an obligation on a storytelling level. Our role was to be the witnesses to this, whatever happened. As you said, it’s a difficult film to watch, it was a difficult experience to unfold. There was a sense that we have to complete this.

Keith: It’s funny that Terry wanted us back—I’m staring at a Lost in La Mancha poster with his signature on it that says “Keith and Lou, this definitely is the last time I let you in on my little secrets”—so I was a little surprised he wanted us in on the next chapter.

Terry Gilliam is someone who tends to have no filter. The film is a very honest portrayal of his struggles while making The Man Who Killed Don Quixote – but of course he has a private life, and you want to respect his right to privacy at the same time as doing your job. How hard was it for you to navigate that balance?

Keith: For his desire for privacy and our desire for good drama?

YES!

Keith: He really isn’t all that private, so it’s not really much of a challenge with him. There are very few times he shoos us away. You see it in He Dreams of Giants: he is coming up to us with his catheter bag strapped to his leg and pulling up his pant leg saying, “you’ve got to have a look at this!” This is not your average person!

Louis: On the privacy issues, there is more of an overall portrait of a man who was at the time 77 years old and felt, “oh my god I’m tired, I can’t do what I used to do.” I think one of the painful things about the film is to see him in that state, and it is probably something he doesn’t want to see, he doesn’t want to be reminded of that. None of us wants to be reminded of that. That was the kind of stuff that made the film feel to us like this is about more than just Terry Gilliam making his film after 20, some 30 years. There is something deeper and human about what happens to any creative person, or any person when they sense they are coming to the end of their life. Hopefully, that’s not anytime soon for Terry, but still, in the grand scheme of things, those were the things that were really kind of private and make somebody feel vulnerable. That Terry was willing to let us show that was … I think that aspect of his experience was what we had to be the most reverent towards, and most careful with.

I’ve seen all of the making-of documentaries you have made on Gilliam films previously—one of the strengths of the current documentary is the way you edited the first 20 minutes. How hard was it to edit down the material about Gilliam’s previous attempts to make Don Quixote for viewers who haven’t been following the story the way I have?

Keith: I don’t think any cuts of our film were particularly long, he had much more footage on Lost In La Mancha than he had on this one. At one point early on in our post-production process, we had a four-hour selects reel, which was just long takes of Terry’s face. When we say this particular selects reel, oh my god, this is the movie, the movie is playing out in these long takes with Terry’s face. Because we were thinking, this movie is not about him making a movie, this is what’s going on in his head as he faces the prospect of finally finishing a film he has been trying to make for 30 years. We actually had a much more experimental cut of this film prior to the existing cut, experimental in the sense there it was designed to play out like a dream or a nightmare that’s going on in Terry’s head. Not very chronological. The current version of the film is quite chronological. We had all kinds of different versions of this film till we finally got to what we got to.

Louis: I think part of the reason we wanted the sense of being in Terry’s head is the 30-year history he is carrying with him on a storytelling level isn’t so interesting for all its details. It’s more interesting as little fragments that are signifiers of this great weight of attempting (and attempting, and attempting) that Terry was carrying around with him, which you could sense on him.

I think it is very effective as an immersive experience in his head… which is an interesting head to be in.

Were there any marked differences in how the 2000 attempt and the final film were in terms of what was happening on set during your filming, other than Gilliam’s health problems the second time around?

Keith: I think the difference was Terry’s level of enthusiasm. We always thought of him as somebody who very actively and excitedly rallies people around him to do what he is about to do. While he was doing that to an extent on the 2017 production, there was just an anxiety in him that we hadn’t seen before. As he says in He Dreams of Giants, “the expectations were way too high, everybody is thinking I’m about to make my masterpiece and I’m not sure it’s going to be my masterpiece.” Lost in La Mancha had made The Man Who Killed Don Quixote into a cause celeb on a massive level, so I think his anxiety and his lack of confidence came from the fact that he hadn’t been in front of a camera for a really long time. He feels to some extent the world is changing around him, he isn’t sure of his relevance anymore and he is very aware of that. All of this stuff is swimming inside of him. I think it’s night and day who he was in 2000 trying to make the film, and who he was in 2017.

Louis: Ian, I think the other big difference is the landscape of movie-making has changed, audiences have changed. People are interested in different things than they were in 2000. If anything, it became more Quixotic in the sense of an anachronistic character trying to accomplish something great.

I also think The Man Who Killed Don Quixote itself became a much more personal movie than what he would’ve made in 2000.

Keith: Oh yeah, in 2000 it didn’t have the backstory of the filmmaker, the script changed quite a bit since 2000.

What do Gilliam and his family think of He Dreams of Giants, now that there has been time to get some perspective on the events?

Louis – We haven’t spoken to them recently, I imagine it’s a pretty difficult film to watch in the same way that you found it difficult to watch. If it were me on camera, I would never want to watch it again. This is a testament to Terry as an artist, and a champion of creativity and creative people, that he lets us show this, he lets an audience see this.

Keith: He has certainly seen it! He has seen it a few times! I don’t think he is a great fan of it—would you be? is the question.

What is your favourite of Terry’s films?

Keith: That is a difficult one, I think it’s still Brazil.

Louis: It’s Brazil for me too.

I would agree

Louis: Part of that too is, Ian, I saw Brazil when it came out in the movie theatres and I was, I don’t know, 19? I was a film student, and that film played a really important role in my interest in becoming a filmmaker. That was the film that made Terry a hero to me.

My dad dragged me to see Munchausen, and this was years after it was out. I was 7 and I was all “I don’t want to see an ‘old’ movie”—and it was the film that blew my mind. After that, I wanted to be involved in film in some fashion, but Brazil is my favourite. I‘m also a big fan of Tideland, which I think is actually very “sweet” and was very misunderstood.

Louis: Yeah (in agreement on Tideland).

What are you working on now?

Keith: We have been working on an “experimental pandemic film” since April of last year. We sent out a call to work for filmmaker colleagues all over the country and did a series of interviews all over the country. We are crafting this bizarre, I would say sort of science fiction movie about the emotional experience of the COVID lockdown of early last year. We have been deep in that for months now.

I hope it’s one of the “good” COVID movies, because they are very few.

Keith: It’s a dark one, depends what you mean by “good”… we like it.

Louis: It’s a trippy film!

You can find more of my words at Psychotronic Cinema.