A Cinema full of Monsters – Part 1

With Godzilla versus Kong due on 26th March (watch the trailer here), now is a good time to check out the history of monster movies.

Monsters have been with us in movie theatres almost since the beginning. They have shaped cinema. Movie effects were born for monster movies and evolved with them. We’ve followed fangs, claws, and giants throughout cinematic history, right up to today, and while the genre is weaker now, it’s given us a legacy that the greatest modern auteurs have spent wisely and joyously.

Before we begin, I should say I’m not going to talk about human monsters. Ed Gein and his ilk may have spawned cinematic classics like Psycho, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Silence of the Lambs, but I’m going to stick with things that slither, crawl, stomp, rend, and go bump in the night. There have been enough human monsters around in the real world recently, so let’s stay fantastical instead, and let’s start by working out what monsters are.

The Word.

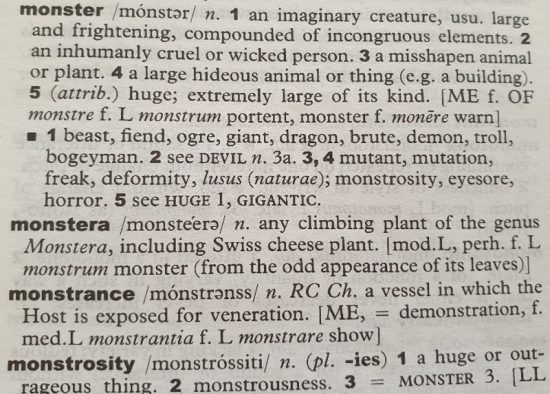

The Cambridge Dictionary defines ‘monster’ as ‘any imaginary frightening creature … one that is large and strange.’ Hmm. Many of the animals in these movies are dinosaurs. They’re not imaginary. Neither are sharks.

The history of the word ‘monster’ is interesting, originating with the Latin ‘monstrum‘, meaning “a divine omen (especially one indicating misfortune), portent, sign” or “a supernatural being or abnormal shape or object that is a warning of the will of the gods.”

The word ‘monstre’ appeared in old English around the early 14th century, meaning “malformed animal or human”, and went on to include the kinds of mythical creatures we still think of today – unicorns, Pegasus, gryphons, dragons, and the rest.

The old English poem Beowulf appeared around 1000 AD, three centuries before the word ‘monster’, and despite featuring Grendel. In Beowulf, ‘āglāc’ is used, meaning “distress, torment, misery”. By the late 14th century, monstre absorbed this meaning, and not until the 1520s did the word also come to mean something ‘of great size’.

The names we give things often tell us more about ourselves than them. Art is similar. Many of these films are omens, signs, and warnings.

The term “monster movie” didn’t become part of our language until 1958. Unsurprisingly, those Fifties movies were obsessed with the atom bomb. Godzilla films originated in the only country to have suffered the use of nuclear weapons during warfare. Consider this portentous line from 1954’s Them! about gigantic, irradiated ants in the New Mexico desert: “When Man entered the Atomic Age, he opened the door to a new world. What we may eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict.”

Monsters take over the world.

The films follow a similar path from portent to giant. The new medium told tales of folklore to thrill audiences. Fragments remain of the 1915 film The Golem, loosely based on traditional Jewish stories, and is one of, if not the earliest monster film. A golem is a creature of stone or clay. Here, an antique dealer animates one for gain, rather than for the golem’s folkloric role of protection. It falls in love with the dealer’s daughter and obsesses over her. Watching what’s left of the footage today, what is clearest is the golem’s relentlessness, a key trope of monster films to this day. Why? Well, the prosaic answer is because otherwise, you wouldn’t have a plot, but since the word ‘monster’ means ‘warning of the will of the gods,’ such an enemy is hard to defeat, needing willpower and grit (or, in the Fifties, more nukes…).

The films follow a similar path from portent to giant. The new medium told tales of folklore to thrill audiences. Fragments remain of the 1915 film The Golem, loosely based on traditional Jewish stories, and is one of, if not the earliest monster film. A golem is a creature of stone or clay. Here, an antique dealer animates one for gain, rather than for the golem’s folkloric role of protection. It falls in love with the dealer’s daughter and obsesses over her. Watching what’s left of the footage today, what is clearest is the golem’s relentlessness, a key trope of monster films to this day. Why? Well, the prosaic answer is because otherwise, you wouldn’t have a plot, but since the word ‘monster’ means ‘warning of the will of the gods,’ such an enemy is hard to defeat, needing willpower and grit (or, in the Fifties, more nukes…).

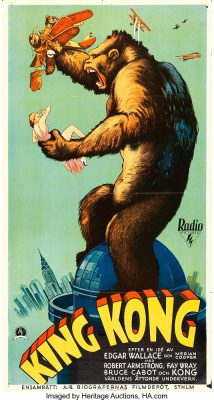

Eighteen years later, Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack directed and produced the granddaddy of monster films, inspiring generations of filmmakers and several remakes, none of which are fit to touch the boots of the original. The importance of King Kong to the cinema is difficult to overstate.

The movie grossed more than any other film that year (though not in its decade), but the influence is more important than the finances. The echoes of King Kong and its effects grow louder with every decade. It was a bold statement of what film could be for. Willis O’Brien created the effects and went on to work with a young Ray Harryhausen on Mighty Joe Young. Harryhausen would, of course, become an effects legend.

The film may not have aged well. Whether the plot is a racist allegory or not, its depiction of the inhabitants of Skull Island is troublesome. Nevertheless, I’d still love to experience it with those first audiences when someone finally invents low-cost time travel. After King Kong, the monsters got bigger, in every sense. Effects would become as important to film as the actors and the story. Forty years later, Jaws may have become the first blockbuster, but the shark has gorilla DNA. After the success of Jaws, Dino De Laurentis wanted Spielberg for his 1976 remake of King Kong, but wisely the young filmmaker declined, making Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Every contemporary event movie from Wonder Woman to the Fast and the Furious, owes a debt to King Kong. Again, there is a meta-mirroring effect. The Golem, Kong, and the shark in Jaws are relentless; the effects-laden event movie is utterly dominant, with lists of the highest-grossing films from the last three decades rarely allowing room for anything else. It all started with an angry ape.

So, monster movies weren’t just showing giants, they became giants. Already in bed with horror, the romance would bloom.

Genre or Sub-genre?

Childhood fear is cyclical. Everything is new. Lots of things are scary. A scary movie you see as a child becomes part of the pantheon of night-time terrors you must battle past to sleep well.

Horror films use this, both by elevating childhood fears (clowns, dolls, monsters under the bed), and by tapping into the residual insecurities we face as adults. An infamous scene from the 1922 silent film Nosferatu has entered many nightmares. For those who don’t know, Nosferatu is an unofficial (i.e., they didn’t buy the rights to the novel) Dracula movie. Count Orlock stalks a renamed Jonathan Harker and his wife. The most striking thing about Orlock is his physical appearance. His shadow is “abnormal”, “strange” and “malformed”, with his stooped frame, hook-like nose, and talon-like fingers. In short, he is monstrous in both deed and appearance. The Count Orlock vampire had a much stronger impact on me than the later slick black-haired version. Orlock is simply more frightening. The image of his shadow creeping inexorably up the stairs haunted me for years. Again, nightmarish relentlessness. You can fight, you can run, you can hide, but the monster is coming for you, no matter what.

Nosferatu, like The Golem, didn’t trouble the box office. Indeed, the closest thing to a monster movie in the top ten of the silent era Is 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea from 1916. Interestingly, however, despite its cultural importance, King Kong is not the most lucrative monster of the Thirties. That honour goes to James Whale’s Frankenstein released two years earlier, in 1931. Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster are the Universal studio’s equivalents of DC’s Superman and Batman. Who rounds out the Trinity, as the equivalent of DC’s Wonder Woman? Surely The Wolf Man, but you could make a convincing argument for The Mummy. Either way, the Universal monsters (also including The Invisible Man and The Creature from the Black Lagoon) are icons of horror. Yet a monster flick is far from always a horror flick. The (stretched) link to DC doesn’t end with the Trinity. The Universal monsters had the first shared movie universe, long before the MCU. Frankenstein met the Wolf Man back in ’43. A year later they had their proto-Avengers movie with House of Frankenstein, where Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, and the Wolf Man all appeared. Frankenstein met Abbott and Costello five years later, which hastened the move of these iconic characters into parody… only a short hop to The Addams Family, Carry on Screaming, and The Monster Squad (excuse me while I go buy a copy of The Monster Squad.)

Monster movies simultaneously evolved in a different direction. King Kong’s key characteristic is his size, and after those gigantic wooden gates opened on Skull Island to reveal him, a whole host of giant monsters would follow him through. Godzilla (1954) is the most famous of these, (although heavily inspired by an earlier American film, as well as the re-release of King Kong two years prior). Giant dinosaurs and lizards, octopi, assorted insects and arachnids, birds… all manner of beasties, but size mattered. As a kid, I liked Gorgo (1961) and The Land that Time Forgot (1975). Gorgo takes place in the UK and has a fun twist when the protagonists realise the enormous dinosaur they have foolishly put in a circus (like King Kong) is a baby… and his mum is pissed. The Land that Time Forgot has submarines and dinosaurs(!) and stars Doug McClure, who you may remember from being endlessly parodied on The Simpsons (apparently the actor enjoyed the joke).

None of this is to diminish Godzilla of course. The franchise is officially the longest-running in cinema history.

So, by the Fifties, we had two distinct strains: the Universal monsters of horror and the giant beasts inspired by Kong. Is a monster film always a horror movie, or a film in its own right? Of course, both are true. Do monsters act as a gateway drug to ‘true’ horror? Spielberg and co appeared to think so.

Monsters evolve.

Steven Spielberg, like Stephen King, ‘gets’ kids better than most adults, the fascination they have with scary things. Kids love the thrill of a horror film more than most adults do. Some of the kids in my primary school class shrieked at the shadow climbing the stairs, but none of us looked away.

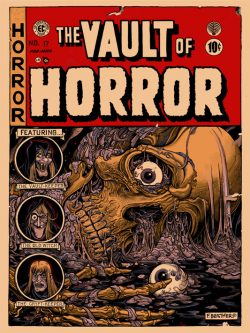

Spielberg and King were born within a year of one another, around the time a moral panic swept America about ‘indecent’ horror comic books published by EC, leading to the Comics Code in 1954. The enjoyably gruesome scene of Nazi face-melting at the close of Raiders of the Lost Ark, which may as well have featured in one of those EC Comics, reads like the rebellious child inside the director pushing back against censorious adults.

King and Romero’s Creepshow, released a year after Raiders is nothing but an extended love letter to EC. I’ll come back to King shortly, but Spielberg got the ‘gateway drug’ concept better than anyone. So many of my generation crossed the bridge he built to King and the harder stuff. The makers of Stranger Things understand this, which is one of the reasons they trigger such a massive dopamine hit of nostalgia with every episode.

King and Romero’s Creepshow, released a year after Raiders is nothing but an extended love letter to EC. I’ll come back to King shortly, but Spielberg got the ‘gateway drug’ concept better than anyone. So many of my generation crossed the bridge he built to King and the harder stuff. The makers of Stranger Things understand this, which is one of the reasons they trigger such a massive dopamine hit of nostalgia with every episode.

Gremlins (1984), directed by Joe Dante, and influentially produced by Spielberg, received a PG rating in the States and became one of the films which led to the creation of the PG-13 rating. The BBFC rated Gremlins 15, a rating as substantial as a Jacob Rees Mogg bench press. The movie was a rite of passage for eleven-year-olds. Steven Spielberg’s fingerprints are also all over Poltergeist (1982), with the… deeply weird tonal balance you’d expect when the directors of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and ET work together on the same film. Poltergeist seems an anodyne, sparkly ghost story… then suddenly a guy tears his own face off! This was a PG movie (at least in the US). Now, despite having monsters, Poltergeist belongs firmly in the horror genre. However, once again, Spielberg is smuggling horror into something kids like. The best horror film of all time (argue with me, I dare you) is also very definitely a monster flick and was also rated a UK PG, sneaking in under the surface to scare the bejesus out of audiences for decades.

When Spielberg gave us Jaws in 1975, he changed the world. Cinema became something other, an entertainment juggernaut which grew in momentum until video games, streaming and an inevitable pandemic bit down. Hollywood had been struggling financially, Jaws gave cinema an adrenaline shot to the heart. Jaws rendered film critics irrelevant for huge swathes of the cinema-going public. The whole method of film release changed because of Jaws. An afterthought before Jaws, Summer became the most profitable film season.

I want to leave politics out of this wherever possible. Even though horror films often deal with issues that regular films shy away from, we can do without it in 2021. However, Boris Johnson deliberately and repeatedly compares himself favourably to the Jaws mayor, joking he’s his political hero, and now, in the face of a threat to his citizens which makes a man-eating shark look like an angry Chihuahua, he responds in the same way! Swap Christmas for the Fourth of July.

Anyway, arguably the most impactful movie in the history of cinema is a monster movie. In the book, the shark is twenty feet long, the same size as Deep Blue, a 50-year-old female and the largest living Great White ever seen. On average, they’re much smaller. For the movie, Spielberg wanted the fish to be bigger yet, so ‘Bruce’ grew to twenty-five feet which checks the size box. Moreover, like The Golem, the shark is relentless, almost unstoppable. Best shown in the second half, when the beast resists the buoyancy of Quint’s barrels, unlike any of its predecessors, then single-mindedly destroys the Orca from beneath our heroes, frantically trying to get to the squishy humans within, like a starving traveller ripping open a sandwich packet. Jaws turned me into a shark nerd. I’ve been diving with them. They’re awesome.

People don’t think of Jaws as horror because it was such a huge hit. Everyone saw it, including people who would never voluntarily choose a horror film. But every characteristic of a horror film is there: brutal deaths, jump scares, gore, floating camera and POV technique, an implacable antagonist. Brody may be a man and he’s clearly not a virgin, but he fits the ‘final girl’ template well. More than anything else though, it’s just bloody scary. Familiarity and dated effects have lessened that impact, but go swimming in the sea and tell me you don’t think about it.

That idea of non-horror fans going to horror films is bookended by what is now the most successful horror movie to date: It. It(!) is symptomatic of something we’re getting to, the decline of monster films. Based on Stephen King’s 1986 novel, the first half of a two-part movie adaptation came out in 2017. But where Jaws is a film that smuggled horror into a mainstream movie, ‘It’ smuggled mainstream sensibilities into a ‘horror film’. It’s anemic and devoid of scares. Both films were attended by non-horror fans because both felt safe. ‘It’ was. Jaws wasn’t. If Jaws is a rollercoaster, ‘It’ is a nip to the shops in a Volvo.

It’s a shame because it could have been the ultimate monster film. The book is. Rooted in King’s childhood, all the Universal Monsters appear at some point. So does the shark from Jaws. Rights for the movie would have been problematic and expensive (It was distributed by Warner Brothers. That said, Ready Player One managed). Beyond that though, the book is maybe King’s clearest fictional exploration of the horror archetypes he discussed in Danse Macabre (1981). He argues that there are three monster archetypes in all horror stories: the vampire is pure evil, feeding on others for eternal life at any cost; the werewolf archetype is best exemplified by Jekyll & Hyde as the animalistic desires that the victim/monster tries to suppress; the ‘thing’ without a name is often man-made like Frankenstein’s monster. He adds that the ‘ghost’ and the ‘bad place’ could round out the pack and are often linked (as in The Haunting of Hill House and King’s own The Shining).

All these archetypes are used in the novel, but films other than ‘It’ have used them so much more effectively. The contrast between Jaws and ‘It’ is clear, and we’ll see that if Jaws was a rollercoaster, it was also a climb toward the peak of film monsters. ‘It’, however, is symptomatic of their decline.

In 1979 Alien, initially pitched to studio execs as ‘Jaws in space’, once again elevated monster movies beyond their humble beginnings. There is a highly detailed life cycle for the monstrous antagonist (although toxic corporate greed is the real enemy). We are shown the egg, the larval ‘face-hugger’, the new-born, and the adult. No one has yet shown us the middle age variant, slumped on a couch, reaching over its massive beer belly to scratch its balls while screaming abuse at young people on the TV, but just wait. The alien is one of the most monstrous monsters we’ve yet had on film.

As the title of the film, the word ‘alien’ works best as an adjective. For me, Aliens (1986) is a better film, but as evocative as the title is, it’s a semantic misstep. ‘Aliens’ can only be a plural noun.

And don’t call it a ‘Xenomorph’ (prepare for a rant). Many people now use this word to refer to the monsters in these films. No. Just frigging no.

‘Xeno’, derived from the Greek ‘Xenos’, means ‘foreign,’ or ‘stranger’. ‘Morph’ in biology is a “genetic variant of an animal.” So, the compound word ‘xenomorph’, as used by Gorman in Aliens, is a generic term for an alien life form, of which we learn several have been discovered.

The ‘Alien’ is, and should always be, ‘alien.’ The moment you name it, try to classify, or explain it, you reduce its fear, and mystique, its monstrosity. That’s the fundamental reason why Ridley Scott’s prequel films don’t work. The recent announcement of a new TV series made me groan. The Alien should be nameless, formless, barely seen, never understood. Like the beast which remains unseen in your nightmares but you wake in terror knowing it saw you.

Anyway, there were two spectacular monster films in the Seventies. One can think of the Fifties as the golden age of the traditional monster movie, but the kids born around then took them to the next level and evolved Hollywood in the process. In the following decade, monsters would burn their brightest yet.

Head on over to Part 2 where I delve further into the monsters of the 1980s and beyond.

For more of my ramblings, check out FiskFilm or Medium.