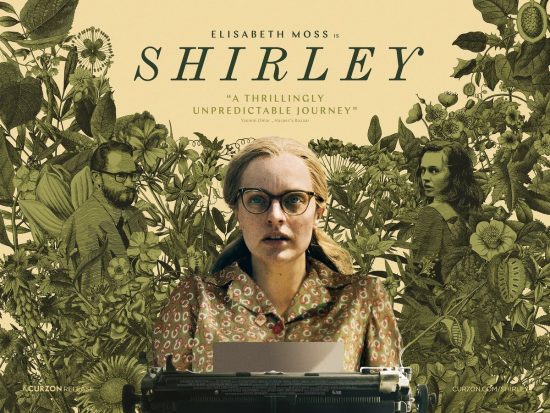

LFF 2020 Review: Shirley – “Full of mystery and sardonic wit”

Shirley is a snapshot of one convention-busting woman’s life as captured by another unconventional storyteller. Josephine Decker’s fourth feature is perhaps her most accessible, one subplot ties in neatly with the modern public’s thirst for true crime stories. But flashes of the experimental style of the filmmaker’s previous films like Butter on the Latch and Madeline’s Madeline burn brightly in this unsettling psychodrama.

Shirley Jackson was an American writer, famous for her gothic horror and mystery stories like The Haunting of Hill House, and The Lottery, her controversial short story published in the New Yorker. It’s a story that continues to both shock and delight readers today.

Adapted from Susan Scarf Merrell’s book Shirley: A Novel, with a screenplay by Sarah Gubbins – Shirley is the story of a fictional period of the writer’s life when a young couple come to live with her and her husband Stanley. It’s not so much a biopic as bio fiction, mixing genre elements of Jackson’s stories with select elements of her personal life interwoven. Her agoraphobia, acerbic wit, and dishevelled yet commanding presence are all wrapped up in a superb performance by Elisabeth Moss.

The story has a chamber-piece setup, with much of the action taking place within the dark walls of Jackson’s run-down, gothic mansion. It’s the early 1950s and The Lottery controversy is a not-so-distant memory. Shirley has been spending a lot of time in bed lately, hiding from writer’s block and small-town gossip about her mental state. Her reclusiveness is interrupted by the arrival of Fred (Logan Lerman), Stanley’s assistant, and his new wife Rose (Odessa Young), having been invited indefinitely by Stanley.

It’s quickly apparent that Stanley’s invitation was somewhat mis-sold to the couple – on arrival, he coaxes Rose into domestic servitude in exchange for room and board. Shirley and Stanley’s gaff verges on squalor, but navigating dust layers and piles of dirty dishes in the house are straightforward problems. Figuring Shirley Jackson’s world out is a bigger task.

There are shades of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? here. Michael Sthulbarg is brilliantly cast as Shirley’s oily, pompous, academic husband. Watching Moss and Sthulbarg go toe to toe in marital chaos is both wincingly uncomfortable and highly entertaining. Their power dynamic shifts as the story unfolds. He is controlling, goading, and philandering – but they also seem to revel in intellectual sparring, particularly in front of guests. The dialogue is often terse – Elizabeth Moss delivers clipped, stinging barbs, between drags on the many cigarettes she smokes. “They talk about me in town…like my dark thoughts are going to infect them.”

The fissures in the Jackson-Hyman marriage rip wide open with the arrival of the newlyweds. Booze-fuelled, vitriolic exchanges between Shirley and Hyman rub up against the wholesome manners of their young house guests. Shirley is particularly cruel to Rose at first, not taking kindly to “sluts interrupting my dinner”, she says, shooting a glance at the younger women from beneath her heavy specs and mass of messy hair. She’s deliberately out of step with her peers. Shirley’s appearance and attitude are two fingers up to the twinset and pearls politeness of middle class, small-town America.

Rose bears the brunt of Shirley’s boozy bad temper, but their relationship quickly shifts to one of mutual fascination. The bigger threat to Rose is Stanley, who frequently corners her with sexual harassment and petty criticism. She may be dismissed and objectified as an ingénue by Stanley, but Decker doesn’t linger on the male gaze for long. From the way Rose is turned on by reading The Lottery on a train, to the look of deflation at being denied a liberal arts student experience at Bennington College – flashes of rage and passion lie beneath a prim, compliant facade.

But Rose gets drawn into Shirley’s orbit, and the two form a bond that is part unusual friendship, part artist/muse dynamic. Decker plays with contrasts and parallels, blurring fact and fiction, the fine lines between perception and reality, and ambition versus societal expectation. Shirley is a masterful study in the different forms of female desire – sexual, personal, creative, and the heavy prices women paid (and often still pay) in pursuing them. The point of view shifts between Shirley and Rose, which some may find jarring. But it’s a deftly-handled device that gives space for both women’s interior lives and exploring how they see one another.

Cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen’s fluid, handheld camerawork captures the elements that crackle through Shirley Jackson’s life – witchcraft, substances, dirt, fire. As in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, flames are a potent metaphor. What burns deep beneath the surface must rise up at some point. With Rose around, Shirley is writing at a pace again. She obsesses over the real-life story of Natalie Waite, the young Bennington College freshman who disappeared on a mountain hike. It’s the story that inspired Jackson’s 1951 novel Hangsaman. Her fever-dream visions projecting Rose as the missing student ramp up the melodrama and ambiguity of the third act, anchored by Tamar-kali’s tense score. And like Jackson itself, the film has plenty of fun wrong-footing its audience as it unravels.

Shirley is full of mystery and sardonic wit. Much like Jackson and the stories she wrote. It’s quite a trip.

Shirley screened at LFF2020 and is released in the UK on 30 October.