Director Benjamin Ree talks to Live for Films about The Painter And The Thief

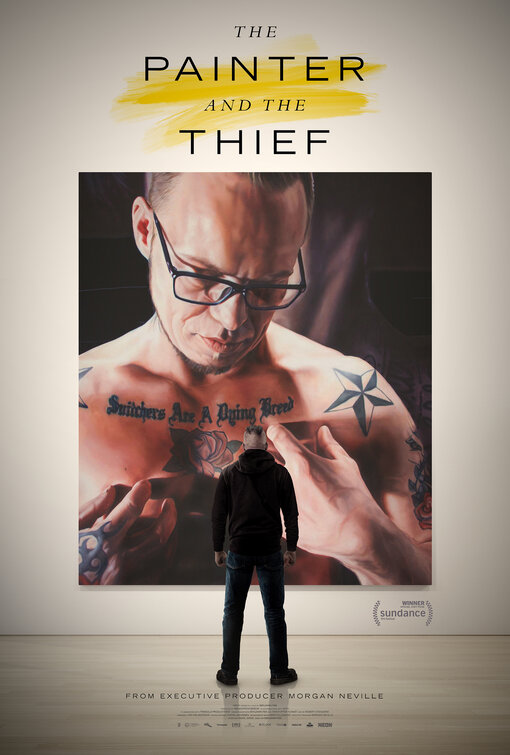

Benjamin Ree’s new documentary The Painter And The Thief is currently showing at the London Film Festival. You can read my review here. The film charts the story of the artist Barbora Kysilkova’s bond and friendship that develops with Karl-Bertil Nordland, the man prosecuted for stealing two of her most valuable paintings from a gallery in Oslo.

We sat down with Benjamin via Zoom to talk about the film and the incredible story it tells.

How did you come across Barbora’s and Karl-Bertil’s story and what drew you to decide to make this film?

A fascination with the high culture art world and the low culture kind of, robbery world and then I read about this. It was on the front of newspapers in Norway and Danish newspapers and I immediately contacted the painter, Barbora and you know, it always takes a bit of time to get access, especially in a situation like this to get access to an actual robber, a thief. I got access to begin filming the fourth time they met each other. By that time I already had a lot of archival footage because a friend of Barbora documented her art life, taking photos, filming her art life. And when I began filming, I did not know anything where the story might end up. I was actually going to make a short 10-minute documentary, that’s what I was going to make. And then I saw that they really had a great chemistry and I was so fascinated and curious, why they had that kind of chemistry. I think that what changed this whole film was the scene when Karl-Bertil sees himself painted for the first time in the film and then I really understood that we are onto something different than I was expecting. Because that reaction came as a total surprise to us, you know, to that point, we thought of Karl-Bertil as a really tough guy with a lot of tattoos, eight years in prison, ‘Snitchers Are A Dying Breed’ and to see this man, tearing up in that way. I’ve never experienced anything like that, ever in my life. I think that was an extraordinary scene to capture, and that changed the whole film.

The film shows several other scenes of really raw, low points in Karl-Bertil’s life and Barbora’s as well and they come across as very vulnerable. How difficult is it for you as a filmmaker, while you’re capturing that, to remain neutral if you like, when there are such deeply upsetting and raw events taking place in front of you?

It’s very difficult. Especially in this film because Karl-Bertil almost died several times, and that makes this film very difficult ethically as well. Shall you continue filming? Shall you intervene with what’s happening, so you can give this person a hug? That’s a huge dilemma and I also tried to reflect back on Barbora in the film, when she sees the scar on his hand. With this film, I have never worked on a project that has been so ethically demanding. Karl-Bertil and me, we actually had conversations where we both thought he was going to die because he almost died so many times and it was just pure luck that he survived. And I said to Karl-Bertil, ‘If you die, we’re not going to make this film.’ And his response to that was, ‘If I die, you have to promise me to make this film.’ So we had a lot of conversations like that and we talked a lot about this. But what you don’t see in the film is, of course, the contract, the common understanding we have before filming. So usually with this film, it was Karl-Bertil contacting me and asking me if I wanted to film, as he wanted to shoot the ugly truth of drugs. So he contacted me before going into rehab and wanted to have that as a portrait about himself in the film. Our common understanding and contract was that I should just observe and continue filming and not intervene in the situation. But, I do believe that when it’s a life and death situation, you shall intervene as a documentary filmmaker. We did not end up in a situation like that, fortunately, but there were really, really many tough scenes to film.

The film speaks a great deal about the incredible bond and friendship Karl-Bertil and Barbora have as their relationship develops and over the period of filming, did your relationship with them develop in ways that you weren’t expecting?

Absolutely. I think I have never been so close to anybody during filming and we filmed for three and a half years. We met each other every week, and many times, several times a week. So I think that although I had a camera with me every time we met, and that was the contract and understanding, I think that we also gradually became friends during filming. I think that friendship is of course a bit strange when I’m there with a camera. I will call it friendship because we really trusted each other and had a lot of fun. But that friendship has become a more serious, real friendship after filming because now I am meeting them without the camera and we’re a bit more even if you know what I mean. So yeah, we all became really close to each other during filming.

As you just said, you filmed over a three and a half year period, and so you must have gathered a huge amount of footage during that time with both covering their relationship and the interviews you completed with them. How did you approach the editing process, with your editor Robert Stengard? How did you begin editing such a long story, with such an amount of footage and did you have an idea at the start of that process, where you wanted to go in terms of the structure of the film?

We knew that we wanted to portray both Karl-Bertil and Barbora in a complex way. I think for me, dramaturgy is not only an artistic choice in a documentary, it is also very much an ethical choice. So to portray a real person that has to live with the film for the rest of their life, to portray that person in a complex way, I think it’s very, very important and it touches upon the ethics of documentary filmmaking. So, during filming, we knew we wanted to portray Karl-Bertil in a complex way as well and the only way to do that was to see the world from his point of view. But it was actually in the editing room we found out that we wanted to jump back and forth in time and see overlapping scenes. That decision we made because for me the film is about what we humans do to be seen and what it takes for us to see others. So to see overlapping scenes and to see how they view each other was very, very relevant to explore the themes in a complex way. So that was the reason why we did that and it was a lot of fun. And I haven’t seen a verite documentary that has done that before and it also makes the film a bit self-reflective in a way because, as with the commentary in the editing process, there are so many ways to edit a scene. You can edit a scene from being about loneliness to becoming about togetherness, just by editing one scene. So, we also explore how there are so many ways to tell and see a scene. And I think that also makes this film a bit self-reflective in a way. I’m the one that interprets the point of view of Bertil and Barbora.

As a filmmaker, has this experience affected how you might approach future projects?

Absolutely. I think that this is the first film where I have really felt that I have found a kind of style and a vision. And I will continue with my two new future documentary projects are both kind of ‘reality stranger than fiction’ projects. But also projects where I will try something new in the documentary genre, so try something from my experience, that hasn’t been tried before. So I will continue to play with form and take some chances. Maybe I will fail but maybe I will succeed, we will see.