Stanley KuBLOG: Full Metal Jacket – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Full Metal Jacket has the dubious honour of being the first 18 certificate film I saw at the cinema. I was fifteen years old and already a huge Kubrick fan. I remember the screening well because it felt dangerous. The film had the feeling that something horrible could happen at any moment. Perhaps the cinema manager would realize a fraud had been perpetrated and I would be unceremoniously tossed out onto the street.

There’s a story about Samuel Fuller seeing Full Metal Jacket and on exiting the theater calling it ‘another goddamn recruiting film’. Many would disagree, arguing that the film’s anti-war message is clear. But on my first viewing, I had to admit that the drill sergeant harangues were amazing, compelling. The recruits weren’t the only ones being brainwashed; we the audience were as well. Charmed, amused by his scabrous wit, bullied, browbeaten: Hartman played with famished glee by R. Lee Ermey points into the audience like the famous ‘I want you’ recruitment poster. In Anthony Swofford’s memoir of the first Gulf War Jarhead, he describes how prior to deployment the platoon hired a cinema and screened a marathon of war movies – Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, many of which would be touted as anti-war films – as a way of getting riled up, salivating for combat.

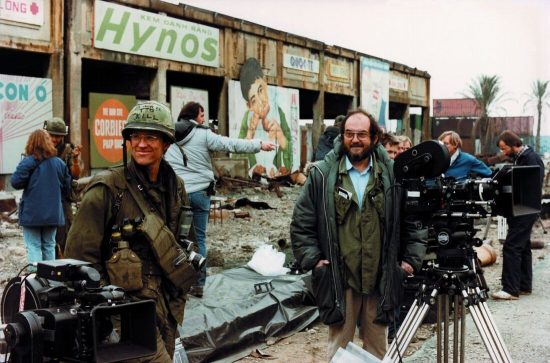

The film follows a group of soldiers through the Parris Island training and into Vietnam combat. Much of the criticism of the film notes how the first section is much more powerful than the more familiar combat film that follows. I’d contest this. Partly it has to do with the context in which it first came out. Vietnam had been treated rarely – Go Tell the Spartans was something of a prequel, The Green Berets a John Wayne led fantasy and Apocalypse Now a Wagnerian work of myth-making, and similarly prone to fascist appropriation. With the release and popularity of Oliver Stone’s Platoon, the floodgates opened and a whole slew of Vietnam films were released, and when Kubrick’s film appeared it felt like the great director might simply be cashing in on the trend. Hadn’t his last film been the crowdpleaser The Shining based on one of the most popular novelists of the time? However, on reflection and away from the noise of all that friendly fire, Full Metal Jacket stands out as a truly great film.

Basically, we have three chapters. The training camp features a superb performance by Vincent D’Onofrio as the brutalised Private Pyle. Matthew Modine as Joker emerges as a possible leader, an ironic voice who maintains some vestige of personality even as he enthusiastically goes through the training. He also provides the voiceover, which is partly provided by Michael Herr, the author of Dispatches and the voiceover in Apocalypse Now. Hartman is the most compelling ever-present voice, haranguing and singing, obscene and holy, a pure force of will. As a teacher, he is not up to much. With a little patience, Joker manages to get Pyle over an obstacle on the course that he previously baulked at. But that isn’t really Hartman’s role. He is there to make killers, and if that involves dehumanization then so be it. The second chapter of the film abruptly takes us to Da Nang where Joker – now a sergeant – is working as a reporter for Stars and Stripes. In the rear with the gear, it is unclear whether Joker has actually seen much action, or fired a shot in anger. Although new recruit Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard) is placed in the role of the new blood, Joker also has a privileged position, happily maintaining an ironic distance from the action symbolised by his wearing of a peace button ‘to symbolise the duality of man, kind of a Jungian thing.’ When the Tet Offensive attacks the base, Joker is obviously shaken: ‘I’m not ready for this man’. Far from the cocky, hardened soldier with his talk of thousand-yard stares.

Sent to Hué City, which has been taken by the NVA, Joker and Rafterman hop on a helicopter with a machine gunner who guns down anyone he sees indiscriminately, while intoning ‘War is hell’. Sam Fuller would have underlined the moment. The actor Tom Colceri was originally slated to play Hartman before Emery nabbed the role. Following a brief journey through the lines, Joker reunites with Cowboy (Arliss Howard), a recruit from Parris Island days and tags along into combat where the platoon twice comes under fire. This final and third chapter feels like the more conventional war film. Away from the cliched foliage of earlier Vietnam movies, the soldiers fight in an urban environment that looks like a tropical Stalingrad of ruin and danger. Once more, there is the detachment of soldiers who instantly begin to preen themselves whenever the journalists, or later a film crew appear. There’s a running joke where once a soldier knows Joker is a writer they give him their full name and where they are from. There’s also a bitterly ironic attitude towards the military establishment, whether it’s the propaganda of Joker’s job or the Colonel who tells Joker: ‘All I ask of my men is they obey my orders as if they were the word of God.’ Much is delivered directly to camera and Kubrick is, as ever, inventive with his camera. The regimented horizontal glide of Parris Island becomes a low angle travelling shot barely above the debris as we follow the platoon into action, ducking to avoid getting shot. The sniper’s POV is given with a series of zooms. Here looking and being seen have deadly consequences. And when a soldier is shot, Kubrick slows it down and we see the gloop of the blood, a distinct ruby red against the urban grey and olive greens, spiral from bodies. Being shot doesn’t look beautiful or balletic, the way Sam Peckinpah’s slow-motion Wild Bunch or John Woo’s shoot em ups do. A man gets shot in the crotch, another in the sole of his foot. There’s no fantasy here. It looks agonizing and terrifying.

We start by getting our hair cut and we end up in hell. The reveal of the sniper’s identity as a young girl no longer feels as shocking as it once did. Joker’s final decision to shoot her, as an act of mercy, is compounded by the very real possibility that this is his first kill. The duality of man indeed. Gustav Hasford’s book The Short Timers, on which the film is based, includes a passage which – and I’m quoting from memory – says that war is truthful. That bullets don’t say ‘I’m kidding’. The soldiers singing the Mickey Mouse Club song as they march through a burning city at the end feels like romantic postmodern irony, at once saying I’m kidding, but I’m also totally serious. This song is ironic given where we are, but we all want to be children again. Declaring ‘War is Hell’ as you shoot civilians. Samuel Fuller was wrong. This is not a recruitment film, but neither is it an anti-war film. It’s both.