Stanley KuBLOG: The Shining – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Approaching The Shining is daunting. Of all Kubrick’s films, it is the most discussed. 2001 and Dr Strangelove, discussion feels redundant. A Clockwork Orange gets jammed in its controversies; Barry Lyndon is safely rehabilitated as the hidden masterpiece. But The Shining has an enigmatic pull which forces viewers – including me – to come back to it again and again. And so here we are at the Overlook once more.

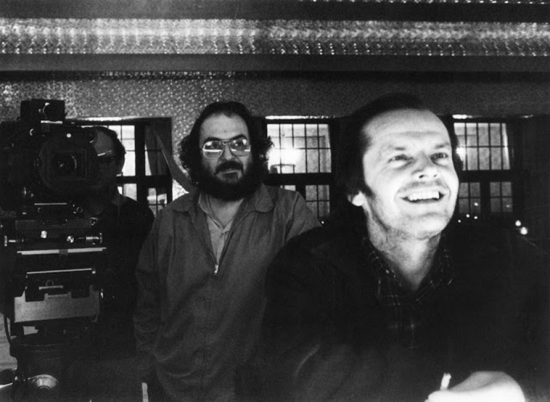

The strange uncanny power of the film has inspired a raft of conspiracy theories and interpretations and even a feature-length documentary charting the most obsessive watchers of the film. With such a weight of discourse and chatter, it is difficult to come back and watch the film with fresh eyes. I saw the film on VHS when I was probably about fourteen and then watched it again and again and again. I loved Jack Nicholson and I loved Stanley Kubrick and I was a big Stephen King fan. I had read the book, along with many others. My reading habits had gone fantasy, science fiction to horror and then on to the Beats and the broader sweep of world literature. I’ve recently returned to King and read some of the ones I missed and some of his latest ones. But all that said, The Shining is very much Kubrick’s film – a point which seems to have irked the author considerably. His criticism of the film was only silenced when Kubrick granted him the rights to make a new version for TV on the condition he stopped publicly criticizing Kubrick’s 1980 version.

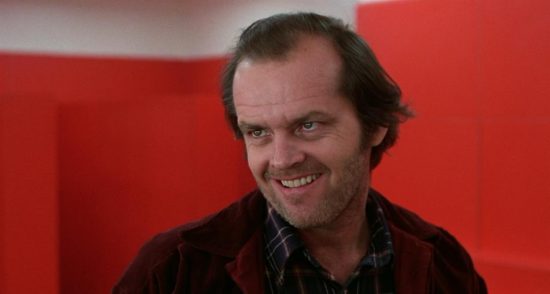

With the first notes of a medieval Dies Irae reimagined by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind toll on the soundtrack as a smooth aerial shot pursues a yellow VW bug as it winds along mountain roads to the hotel. The camera is a witch on the wing, a spirit of the air, giving a god-eye view of the car cuts through the forest in a shot that would compulsory for many horror movies to come. The gliding continues as Jack Torrance walks across the hotel lobby for his job interview. Everything is normal but sociopathically so. Just off. When he calls his wife on the phone – ‘Sounds like you got the job,’ she says excitedly. ‘Right,’ he talks past her. This is a man who we can already tell doesn’t love his wife. And in the car ride up, his barely concealed contempt for his son is on display as well. Stephen King’s book is about a good man who goes bad; Kubrick’s film is about a bad man who goes home.

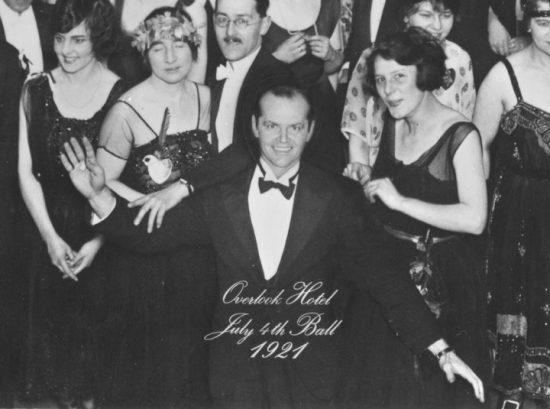

And his son sees more than he is letting on. Gifted with the psychic ability that gives the film its title, Danny – played brilliantly by Danny Lloyd – sees not only into the future but through his father. Chef – who will act as only partly successful Deus Ex Machina – seeks to tutor the child in his gift, but even he can do little but warn the boy off. Kubrick sets up a pace in these scenes which draws you in. Conversations are almost always one on one, maybe with a third listener such as Bill Watson during the interview with Ulman: the bizarreness of which is extenuated by the actor’s physical similarity to Torrance. This is only the first of several doubles throughout the film: the twins are the most obvious, but there’s also the two Gradys – Charles who is mentioned and Delbert (Philip Stone) who interviews Torrance in the infernally red toilets of the Gold Room and there are two Jacks, one of whom was apparently alive in 1921. This mirroring informs the mise en scene which is so symmetrical as to suggest everything has been arranged just so. Chef (Scatman Crothers) lives in a room in Florida with two pictures of nude women and his feet arranged just so to complete the symmetry. His walls are also a similar colour to the hotel. There are two mazes, one an actual maze and the other the labyrinthine hotel.

John Alcott’s photography beautifully captures the interiors and especially the light of the sun reflected on snow through windows. Snow is used wonderfully and the fact that the film was shot almost entirely in England and the Hotel was created inside a studio is breathtaking. There’s a delight in creating such illusions, an imaginary environment which feels so real. And behind everything is the feeling that the film means more than it is saying. Is it about the genocide of Native Americans? Or the Holocaust? Are there references to Kubrick faking the moon landings? Is it a poem to snow? Is it scary?

This last one is the kicker. I wish I could go back and watch it again for the first time ever. I’ve seen it so many times and saw it for the first time so long ago, I can’t remember if I was ever scared of the film. Certainly not in the way the Texas Chainsaw Massacre still is a difficult watch for me. There’s something evil in the film itself. But The Shining doesn’t work on anything as basic for me as fear. I find it disturbing. But these days it isn’t Jack’s madman routine, or the lady in Room 237 that gives me the shivers: it’s the fact that Jack is an abusive husband who doesn’t love his family and there’s only the need for a scratch for that to come to the surface. Some have seen this as a flaw in the film. Wendy (Shelley Duvall) is already jittery before everything starts to happen; Jack is already nuts – and we’ve seen this actor play crazy already. And perhaps this is why the film keeps me coming back. It is precisely its imperfections. The way it doesn’t play by the rules of ordinary narrative or for that matter the generic conventions. In fact, it is frequently at its weakest when it tries to be a straightforward horror movie. Why is this film so good when it isn’t good at the thing it’s supposed to be good at? Well, I’ll watch it again and tell you what I think.