Stanley KuBLOG: Dr Strangelove (or How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb) – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Dr. Strangelove is damned near perfect. Hell, it simply is perfect. From the title with its death wish Nazi sentiment matched with the breezy optimism of a self-help book – How to Win Friends and Influence People pops to mind – to the final evocation of annihilation over Vera Lynn’s We’ll Meet Again, the film makes courageous original fiendishly clever decisions again and again and again. It stands as the best artistic response to both the Cold War and the threat of nuclear war while at the same time managing to achieve that rarest of things: a genuinely funny Hollywood comedy.

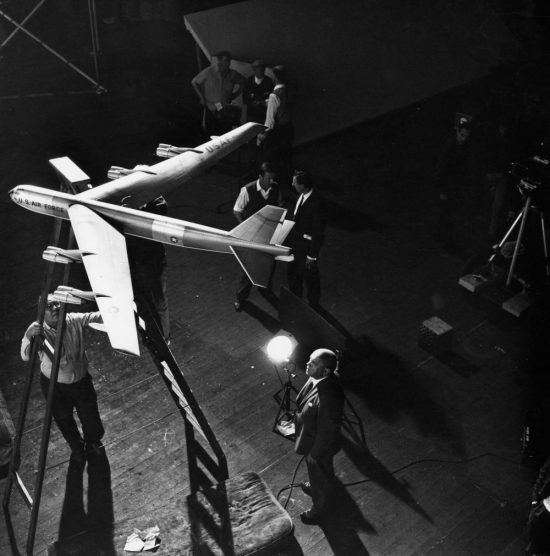

The actual structure and plot of the film is simplicity itself. Three things happen in three different places. In Burpelson Air Force Base, United States Air Force Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) goes rogue and sends orders to initiate a nuclear attack on the USSR in response to what he believes to be communist plot to make men impotent via fluoridation. In a bomber, the crew begin their mission and head towards their target, led by cowboy pilot Col. Kong (Slim Pickens). And in a hastily convened War Room, the President of the United States Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers in one of three roles he plays in the film) attempts to deal with the crisis. Sellers was supposed to also play Kong but broke his ankle though according to one biographer this was probably a ruse because he didn’t feel confident enough about the accent.

The story was based on Peter George’s novel Red Alert, though adapted freely and importantly the genre changed to satire rather than a straight thriller. All the names are broadly comic – Jack D. Ripper, Premier Kissoff, Buck Turgidson – but the performances vary. Peter Sellers plays Mandrake – the RAF officer who is an unwilling audience to Ripper’s diatribes – is played relatively straight. The funniest thing about him is his moustache and his recounting of his experiences as a prisoner of war is actually genuinely moving. Likewise, the President is played with a Gene Wilder straightness, a slightly stuffy nose and a gradually rising hysteria. His Dr. Strangelove is his most Goonish performance. By the time Strangelove is speechifying towards the end to the President, it is difficult to remember that the two parts are being played by the same actor.

Sterling Hayden plays his mad Brigadier General, with a deadly seriousness that his hilarious and terrifyingly real. The original anti-vaxxer, his fear of contamination and his misdiagnosing of post-coital melancholy as some kind of draining of manly essence is both ludicrous and convincing. Slim Pickens likewise plays Kong as his cowboy self, a role that apparently was no different on and off-screen. The tension of the cockpit is all about process – pressing buttons, twisting dials, mapping coordinates. So hypnotically compelling is this part that by the end, I’m always willing the plane on to succeed, even knowing that means the end of the world. But let’s not worry about that.

Of all the non-comic actors, George C. Scott delivers the most outrageous and over the top performance, his lantern jaw chewing gum as he dismisses millions of dead as ‘getting our hair mussed’. Famously, he was a victim to Kubrick’s manipulation as he was encouraged to go over the top for fun, with Kubrick insisting the takes were just rehearsal takes and wouldn’t make it into the film. Then Kubrick chose the wildest ones for his final cut.

As for Kubrick’s direction, it is meticulous. The number of times he places legible text on the screen, usually with ironic intent, seems to invite the viewer to read the film as much as watch it. ‘Peace is our Profession’ reads a large sign during a battle scene. Playboys are read and reports on ‘megadeaths’ are carried about. The attack on the base is shot with a cinema verite handheld camera, point of view shots and a soundtrack a rattling machine guns which anticipates Saving Private Ryan and his own Full Metal Jacket. Something truly Kubrickian starts to emerge as men here – and it is almost exclusively men (the only woman to appear on screen, Tracy Reed , appears as Buck’s lover/secretary and as a centerfold in the Playboy being read in the bomber) – are trapped in patterns and by machinery bigger than themselves. From the Coca-Cola company to the US government, the Doomsday Machine to the communications system, there is a lack of agency which is being taken over by machines.

The film is hilarious, but it is darkly, drily, frighteningly hilarious. The cathartic chaos of the filmed but never seen custard pie fight that was supposed to conclude the film would have dissipated some of the film’s power. The end as it stands comes with the unforgettable image of Kong straddling the bomb as a huge phallus and heads down to ground zero. This closes the thematic circle that throughout has dark sexual insecurities and paranoia as the motivating factor for the nuclear war in the first place. An epilogue which has Strangelove laying out his vision of a Brave New World states a bold fact: the end of the world is possible because enough men want it. The survivalists will live down mine shafts with women – ten to every one man – and Turgidson practically dribbles on hearing the idea.

Dr Strangelove is Kubrick’s first out and out masterpiece. It is a film which spoke intelligently to the fears of the time, mocked its stupidity with satire that was precise and surgical. It is a film of formal simplicity but incredible depth and at the same time manages to be a comic wonder, featuring Peter Sellers in three of his finest performances.