Stanley KuBLOG: Lolita – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Lolita is an odd film but is a first for Kubrick. His first non-genre film, the adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel, tells the story of a literature lecturer Humbert Humbert (James Mason), who falls in love with Dolores Haze AKA Lolita (Sue Lyons), a fourteen-year-old school girl who lives in the house where he lodges.

The major obstacle to making the film was dealing with Humbert’s paedophilia, although some would argue that technically with his love of ‘nymphets’ it is actually more accurately termed hebephilia. In the novel, he can condemn himself out of his own mouth, the ultimate unreliable narrator who ties himself in knots justifying his sexual predilections. Finding a middle-aged star willing to play such a role was an understandable challenge. After David Niven and Laurence Olivier turned the role down, James Mason finally agreed to do it. His performance is suitably lacking in vanity. His debonair charm slides into sleaziness with disturbing ease.

But no one gets to look good. Shelley Winters as Charlotte Haze is a frustrated housewife unaware that Humbert is playing her for a fool to get at her daughter. American society as well is portrayed as shallow, but everything is seen through the lens of Humbert’s desire. The age of Lolita was changed to 14 to make it more palatable to the censors, but making it more palatable might actually be the problem. The bashfulness in reference to actual sex makes Humbert and Lolita’s relationship into something of a May to December romance rather than an act of sexual predation.

The role of Claire Quilty – greatly expanded from his presence in the book – as a dark counterpoint to Humbert is also problematic. Partly, because he is played with such versatile genius by Peter Sellers in the first of two collaborations with Kubrick. The British comic actor would later become an international superstar of the back of the Inspector Clouseau movies – and a monster to work with – but these were the early days and his performance is scene-stealing and the movie lifts whenever he is on screen, or even off-screen but on the phone. Even his first appearance joking about Spartacus gives the impression that this is an element of the film that is attempting to escape the fictive world. This is someone who knows what is going on and his multiple roles give him an authorial omniscience that Humbert doesn’t get, despite his cloying voiceover.

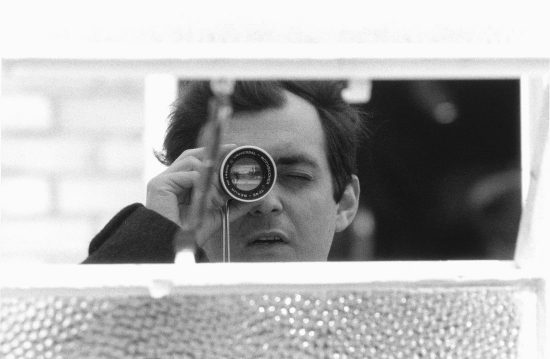

And the given that Quilty is also seen holding a camera at various moments, it wouldn’t be far fetched to see him standing in for the director himself. All of this takes away from the fact that he too is a predator, a more successful, slicker one, a more American one, but no different really from Humbert.

Ultimately, the film simply doesn’t seem to know what to do, morally. This is also because Sue Lyons is fantastic as Lolita, a beautifully spontaneous performance, but never suggestive of suffering on her part. She is in control of all the situations – with a brief weep for her mother’s death – and it is actually Humbert who falls apart and becomes emotionally helpless. Our sympathies are more with him than with her and that is problematic. And the marketing of the film sets everything up to be a sex comedy – Carry On with the Kids – in which we’re invited to share glimpses of the nymphet through Humbert’s gaze: the lollipop sucking, hula hooping, precocious sex kitten.

Following his experience with Spartacus, Kubrick was keen to get away from Hollywood and so shot the film in England, where he had also taken up residence. Much of the film required English locations to stand in for American ones and – as with Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut – they do so only with sporadic success. There’s a noirish quality to the film in how Humbert is trapped and paranoid. In fact, like another old professor in The Blue Angel, this is another man undone by inappropriate desire.

A coolly dispassionate film about passion might seem like a paradox but it is difficult to see how else Kubrick could have made the film and have it distributed. As it is, there were problems and Kubrick himself confessed had he known how hard it would be, he would never have made it. The portrait of small-town America, the prying neighbours, the social evenings and parties, the search for some sort of authenticity all ring true, and there is an unrelenting hardness at the core of the film that showed despite the compromises that Kubrick wasn’t going to soften his vision beyond a certain point. Ultimately, my difficulty in responding to it probably goes back to the genre. It isn’t really funny enough to be a comedy, and it’s too emotional aloof to engage as drama, but that might be more my problem than the films. The mixture will work – at least for me – much more in Kubrick’s next film – another comedy-drama about an inappropriate subject: Dr. Strangelove.