Stanley KuBLOG: Paths of Glory – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Stanley Kubrick’s fourth feature film Paths of Glory is his first to establish him as the complete product. This is the first of his movies where we stop spotting traces of the genius to come and see his first fully-fledged Kubrickian masterpiece.

The Killing hadn’t been a commercial hit but as with both Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss it had garnered some critical praise. James Harris and Kubrick wanted to find another property and Kubrick remembered a novel set in World War One he had read as a kid. The book by Humphrey Cobb retells a true story about the exemplary execution of French soldiers by their own command after a unit refused an order to attack. Jim Thompson was called in again to do an early script and then Calder Willingham came in to finish it off. Willingham would go on to script such New Hollywood classics as The Graduate and Little Big Man. As with The Killing, Thompson felt jipped out of a credit and the credits had to go to arbitration with Thompson’s draft being recognised as surviving in some seven major scenes.

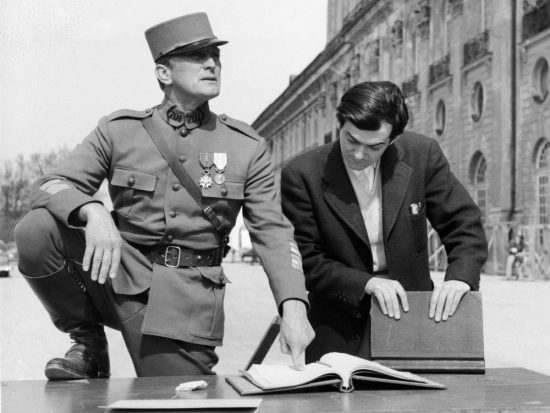

Kirk Douglas was secured as the lead, Colonel Dax, the soldier lawyer who will first command his men in the battle and then defend them in the courtroom. It was a plum role and one of for once shiny liberal heroism. Douglas had excelled in playing the compromised and the corrupt when not the downright villainous. For Kubrick, it gave him a bona fide Hollywood name and a chance at a $1 million budget.

The story is told in a series of distinct scenes. A suicidal attack on the anthill is proposed by General Broulard (Adolphe Menjou), to his subordinate, the ambitious General Mireau, played by George Macready, a veteran actor who co-owned an art gallery with Vincent Price. The conversation of the two officers is a twirling uncomfortable waltz around the interior of the chateaux, as at first Mireau refuses the mission only to concede once the offer of personal advancement is hinted at. These are silky men who speak in code and hide their own venal motivation behind bland statements about the spirit of the men and the need of the nation. When we see Mireau in the trenches, he is repeating a cod speech to each soldier he meets about killing Germans, canny enough to pace them out so he is out of earshot of his previous victim. This comes up short when he meets a man suffering from shell shock. But Kubrick is careful to have background details of wounded and distressed men contrasting the general’s sickeningly banal optimism.

Colonel Dax, by contrast, is a straight-talker, but he recognises that he has his limits. He must hold his tongue if he isn’t to lose his command, even though he also knows the attack is suicide. A night reconnaissance gives not only a taste of the killing to come but also of the unreliability of the officers at every level as a coward deserts and even kills one of his men and then is found by the survivors of the patrol nonchalantly writing up his report in his dugout. History is written not so much by the victors as by the surviving officer class.

Dax’s march through the trenches is rightly held up as one of Kubrick’s first significant tracking shots. It sets up – along with the sound design – the tension of the battle to come. It gives us confidence in Dax’s authority, even as we view the terrified men huddled and awaiting a command that for many of them means death. The tracking shot then continues with the battle, but whereas in the trenches there was some sense of power and agency in Dax, here there is simply inexorable and machinist fate. As men fall all around the advance continues. The camera picks Dax out in the midst of the chaos. Other than the relentless sound of the guns and the artillery, this is no immersive experience of battle. We are as safe and distant as the generals and the camera tracks with the merciless smoothness of the machine gun sight.

The soldiers picked to face execution have already been introduced via a vignette earlier on. Ralph Meeker joins Joe Turkel and Timothy Carey, who had both already appeared in The Killing as the three hapless victims of official anger over the humiliation of the failed attack. Each has been chosen for a different reason – one at random, one because he is disliked by his commanding officers and Carey’s Ferol because he’s ‘a degenerate’, a suggestion of homosexuality. Dax’s control is always brief and illusory. He is confident in his abilities, but the court-martial has dispensed with all but the most superficial of legal principles. He is reduced to satire and contempt. His barn-storming speech is shot in long shot, with Kubrick tracking to follow his walk and the prisoners and their sentries in the foreground. His voice echoes in the cold spaces of the chateaux and close-ups are reserved for the disconcerting view of the off-centre prisoners who are paradoxically being examined and erased by their proximity to the camera. Just as the men who are about to go into battle, stare back at the camera, hopeless and yet accusingly.

There is no tension to the verdict and even Dax seems resigned, although he attempts a last-ditch effort to blackmail the high command when it is revealed that the general ordered the artillery to fire on their own positions. The execution scene is played out in real-time and once more the tracking shot is used to suggest a ritual that must be carried out and shall be. Men are trapped in these spaces and these roles, even the victims are unable to protest – one is strapped to a stretcher, another is in despair. Meeker – who had played tough guy Mike Hammer in Kiss Me Deadly – gives an amazing performance. Baffled by the enormity of his predicament, his mind wholly taken up with the business of being about to die, he only glancingly acknowledges the apology of the officer who sent him to his fate.

Meeker’s performance is perfect as are all of the cast. A director who is often seen as cold to actors, Kubrick begins his reputation with this film as someone who is demanding multiple takes. Kirk Douglas recounts Menjou being asked to do 17 takes before breaking down and yelling at the young filmmaker. At which point he was asked to do it again. Carey proved a difficult player as well, disrupting scenes to make his part bigger, but none of that is visible on-screen and Douglas’ star persona is kept in check. The occasional outburst always feels earned. There’s also a matter of factness about the way the French army speak in American accents throughout. This would be lampooned in A Clockwork Orange when Christ is whipped by a Roman Centurion yelling in a broad American accent, but here it is hardly even a distraction.

Kubrick’s film is a calm and furious denunciation of war and the manifold hypocrisies of those who steer and command it. Although he allows his star, moments of fury and grandstanding righteousness, the film itself maintains an emotional austerity which ends up all the more effective. The ending – a brief glimpse of humanity and solidarity before the horrors of the trenches are returned to – could be seen as cynical but appear to me more insistent on the universality of man. We, an audience, watch another audience emotionally react to something sung by a daughter of an enemy in the foreign tongue of the enemy before going off to be killed by, and kill that enemy. It might be hopeless but it isn’t cynical.

Kubrick will return to the subject of war again in Dr Strangelove, Spartacus, Barry Lyndon and Full Metal Jacket, but nowhere does his anger feel as acute as it does in Paths of Glory. Although the film would be only a modest commercial success, it had effectively opened the door of Hollywood and his next film would be an opportunity to take on a huge subject and a budget to match: Spartacus.