Stanley KuBLOG: The Killing – A Stanley Kubrick Retrospective

Okay, we can stop mucking about now. After a couple of shaky starts, Kubrick with The Killing finally makes a fantastic film. Released in 1956, Kubrick’s film comes at the fag end of the film noir period – Touch of Evil would close the first phase in 1958 – and there is a sense of the walls closing in not only on the protagonists but also on the genre itself.

The Killing tells the story of a daring but meticulously planned racecourse heist which seeks to net the criminals $20 million. A small group of amateurs are held together by seasoned pro and ex-con Johnny Clay, played by Sterling Hayden, himself a seasoned dweller in the world of Noir having starred in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle in 1950. Around him are gathered a crooked cop, a bartender with a sick wife, a clerk (Elisha Cook, Jr. of The Maltese Falcon among many others) with a chiselling wife and an older man who bankrolls the caper and has an obvious crush on Johnny.

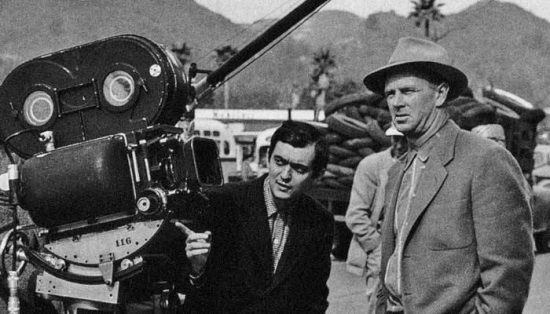

All of this has a meta-quality. Kubrick had also surrounded himself, but with this time with pros. Veteran Lucien Ballard was recruited as cinematographer, giving The Killing a detailed, deep focus in high contrast black and white, which was to become Kubrick’s hallmark. Likewise, the actors were becoming part of a trusted ensemble with Joe Turkel and Timothy Carey among the faces – along with Hayden – who would turn up again in Kubrick movies. A chess-playing pal Kola Kwariana was roped in to play the wrestler who provides a distraction and a great fight scene. For other roles Kubrick was happy to gather familiar faces from other crimes films such as Marie Windsor, known as the Queen of the Bs for her ubiquity in low budget crime and westerns.

Behind the camera, Kubrick was now supported by James B. Harris, an ambitious young producer, who was happy to hitch his star to Kubrick, having met him while playing chess in New York. Importantly, Jim Thompson the author of hard-boiled classics such as The Killer Inside Me and The Grifters took on writing duties. Thompson was spectacularly unimpressed by Kubrick’s stealing of the screenplay credit and seeing himself relegated to a credit for ‘Dialogue by…’ He quite reasonably asked, what else is a screenplay?

But Kubrick was keen to make his mark and his direction now displays a method and style of total control, even as the characters spin out of their own orbits. The use of the racecourse, for instance, includes documentary-style footage of the beginning of the races and Kubrick uses the noises and action like punctuation marks. Behind the scenes – away from the thundering action of the race – is where the story will be happening, in the litter-strewn emptiness of the racecourse betting hall, the car park, the bar, the motels and the bus stations. Take a look at the bar shot featured above. The framing should remind you of The Shining. In the background, the two drinkers are figures from a Charles Bukowski short story. The woman on the left will raise her empty glass and peer into it, a small poem in self-destruction and bitter afternoon sadness right there.

Tarantino claims The Killing as inspiration for Reservoir Dogs and the two films would dovetail as a double bill. Whereas one omits the robbery and much of the backstory of all but a couple of characters, The Killing sets up everyone’s backstory: they are nothing but backstory. The details run through everything. Tracking shots through apartments and buildings follows the characters through walls and furniture into their private traps. The camera has an awesome power. Everything will be revealed and no one will escape. Comments and throwaway remarks reveal all in the naturalistic dialogue that only occasionally dips into the delicious noirish well: ‘Where most women have a heart you a have a ten dollar bill.’ That puppy that Nicky the gunman holds when he’s not boasting of the lethal potential of his wares: ‘You can clear a room with that!’

The heist itself is set up time and again but with a two-steps-forwards-one-step-back rhythm, the film slips chronologically back and forth with the authoritarian narrator trying to keep us from swirling down the plughole. But we know everything must go wrong because of his voice. How could he be narrating this if everything hadn’t gone tits up?

When the actual heist occurs we already know that things are going wrong and it’s mostly the fault of all that backstory. The treacherous wife has tipped off her lover to the plot and he’s looking to rob the robbers. The bankroll feels rejected by Johnny and so he’s turned up to the robbery drunk. Nicky in the car park has befriended the black attendant but now the guy won’t stop pestering him. And Johnny, the brains behind the operation, isn’t quite as smart as he thinks he is.

Violence, when it does happen, is sudden and extreme. Like the blast of the shotgun at the firing range, it has an unexpected loudness and ferocity. But it isn’t dwelt on. This isn’t Peckinpah – Lucien Ballard would go on to film The Wild Bunch incidentally. The Mexican standoff resolves with mutual annihilation that largely happens off-camera. There’s no glamour to the criminals, no real joy in the violence and no thrill in the heist beyond the dread that comes with knowing this is all going to go wrong.

The inevitable downfall comes and here we begin to sense Kubrick’s arrival not only as an eye but as a voice. A philosophical position which will remain remarkably consistent throughout his career. People are trapped and the more they seek to think their way out of their traps, the tighter the wire pulls around their throats. In the end, it isn’t a treacherous lover, or the dedicated power of law enforcement that does for Johnny and his gang. Rather, it’s a cheap suitcase and a little comedy dog who is introduced into the picture late on as an apparent annoyance, a delay at the airport to heighten the drama. Johnny won’t die in a hail of bullets. His heroism – if it can be so defined – is in realizing that he’s screwed and accepting his fate. ‘What’s the difference?’ he mutters as he watches the police approach with their hands on their guns. Fleeing would merely prolong the inevitable. Watching that swirl of money – all that money – blown in a blizzard of banknotes into the air by the jet engines has killed Johnny, totally defeated him.