SpielBLOG: War Horse – A Steven Spielberg Retrospective

Steven Spielberg is sometimes Steven Spielberg and sometimes not. Jurassic Park is very Steven Spielberg; Catch Me if You Can is not. Schindler’s List wasn’t particularly Steven Spielberg but then again neither was 1941. Some films are too Spielberg (Hook). Others are perhaps not enough, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Shite. And yet what is all this about Spielberg? Can such a profligate really have a style? Someone who seems capable of genuinely surprising moves (cf. the under-rated brilliance of Munich and Empire of the Sun)?

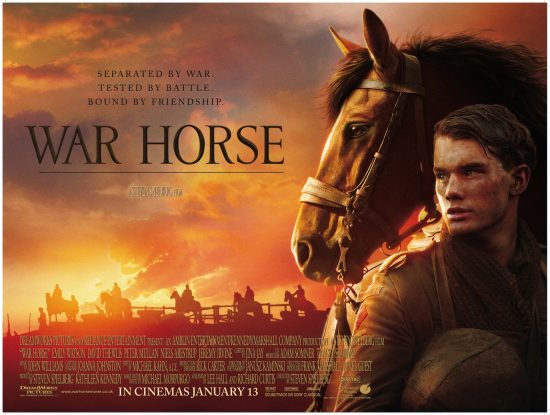

And yet War Horse arrives trumpeted as Uber-Spielberg, Spielberg porn, and at the core of it is the definition of Spielberg who is someone willing to go straight for the tear ducts and we look on that with as much disapproval as someone heading for the gonads. We are (when it comes down to it) emotional puritans.

But I would characterise Spielberg as a Terminator of a director. He might have a superficial coating of soft organic-looking emotion, but underneath there is a skeleton of tough, hard, resilient titanium. Watch Schindler’s List again and wonder who Spielberg is most interested in: it isn’t Schindler or Ben Kingsley’s mentor character, Stern, it’s Ralph Fiennes’ Nazi, Amon Goeth. This can be seen as rooted in Jaws most clearly. The famous boat scene shows you who Spielberg thinks he is (Hooper) but who he wishes he was, who he is genuinely and secretly is Quint. That’s why Quint has to die.

War Horse is ostensibly and actually a children’s film about a magic horse. But like many children’s story this is about magic meeting reality and the uncomfortable friction such meeting creates. The magic horse runs through history and, although damaged by it, survives. The magic horse is Spielberg’s ideal camera, a Peter Pan of inhuman flightiness, which nevertheless bears witness to human folly, sympathizes with human weakness and will ultimately want to to find some sort of fate linked with humanity, but who is essentially and ultimately magical. The horse runs through a series of episodes which half resemble children’s fantasies – boy and his dog friendship, the heroic charge, the two brothers run away, the little Heidi girl who lives with grandpa – but each of these stories are broken by the trauma of history, the First World War. The idylls are destroyed, safety is an illusion, escape and escapism ends in summary execution. And yet Spielberg gets accused of sentimentality?

Even the happy ending seems so consciously belaboured as to suggest that it is a dreamscape, an impossible technicolour fantasy, a reward but not to be taken seriously. The depiction of the battles are bloodless, but frankly, theatrical convention rendered war largely bloodless for a good long time and were still shocking and so are Spielberg’s scenes with a nod to Wilfred Owen ‘Gas-Gas!’ and Paths of Glory. The latter comparison might feel overly ambitious, but this is what Paths of Glory would have been if that film had been made for an audience of twelve-year-olds. I think this film is as hard as it is possible for a film of this genre to be, and the happy ending does not erase the numerous unhappy endings that have come before.