SpielBLOG: War of the Worlds – A Steven Spielberg Retrospective

Steven Spielberg owes a lot to aliens from outer space. His 60s mentality of awe and wonder made for the slack-jawed welcome of Close Encounters of the Third Kind and the glowing heart of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, both were huge successes and went some way to changing attitudes towards the other. Just as aliens in the 50s had been the result of Cold War paranoia, so E.T. showed an 80s optimism. But 9/11 took us to a hot war on terror and War of the Worlds registered a retreat into the old patterns of fear and loathing.

H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds was a very important novel for me. But I only read it because I loved Jeff Wayne’s musical adaptation. So when I saw Steven Spielberg’s 2005 adaptation, I was pleased to hear Morgan Freeman’s sonorous voice intoning the opening lines of the book. It wasn’t Richard Burton, but it would have to do.

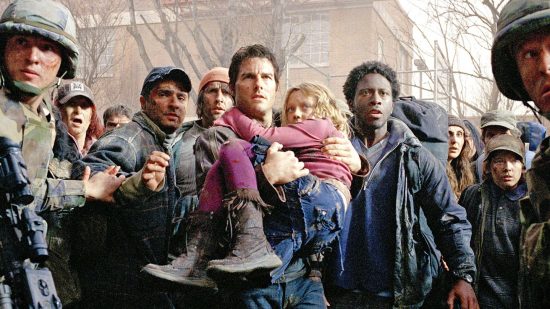

Tom Cruise plays Ray, a dock worker with a broken family. He’s a man child with an engine on his kitchen table and his only way of connecting to his grown son is to throw a ball in the yard. His job as a crane operator shows a globalized world of massive trade and inter-connectivity, technological know-how all ready to be brought to heel by the Martian invasion. Ray has his kids for the weekend, Robbie and the screaming girl child Rachel. He’s working class and his family has become the kind of middle class with allergies and a taste for hummus. In other words, Ray is proto-Trump voter, disenfranchised, lonely and angry, dumb, with an inferiority complex covered up by a sort of smart ass attitude. Barely. The alien invasion lays bare his inadequacy and ultimately sees him step up to the plate.

David Koepp studiously avoided the cliches established by such invasion films as Independence Day – no landmarks getting destroyed, no generals in war rooms – choosing instead to stick to Ray’s story, so that it becomes a refugee narrative. There is a feeling of hopelessness as American strength crumbles and with it any sense of American resilience or specialness. From the city to the suburbs, life begins to fall apart. An airplane crashes into a house that they were sheltering in – though weirdly the bodies are all gone. As with Jaws, Spielberg is careful to measure his gruesomeness. People turned to ash and empty clothes – a train on fire speeding through a still functioning crossing and a ferry crossing gone terribly wrong. The car – that locus of safety and escape – becomes a place of danger and murder, where Americans will murder each other without pity for the advantage it might afford.

And through this Ray is falling to pieces. His bravura is shown to be flimsy and the need to keep his adult son from the running off and at the same time safeguard his daughter proves impossible. Cruise’s performance is reminiscent of James Stewart at his most shrill and it works in stark contrast to his usual superstar persona. One caveat to that are the running and jumping and driving fast car bits which feel like a sop to show off his skill set. But being a hotshot isn’t enough and ultimately Ray is reduced to the most basic homicide – killing Tim Robbins’ crazed ambulance driver.

With Robbins’ status as Hollywood’s most vocal lefty, his murder cements the idea that War of the Worlds is a fearful retreat from such ideas as tolerance heading pell-mell in the direction of devotion to the military and every man for himself. Robbie – Ray’s son – exemplifies this in his mad, suicidal urge to join the military. Herein however lies one of the weakest points of the film. The characterization of everyone around Cruise – with the exception of Dakota Fanning’s Rachel – is so pencil light as to make their decisions and dilemmas mere distractions to his ongoing journey. His ultimate reunion is hugely undeserved and unearned.

But in a sense, this is true of the novel as well. There is a strain that works against Wells’ original narrative. In the book, the narrator – an unnamed journalist – witnesses the invasion and sees the breakdown of British society. For Wells, the analogy was with the British Empire and colonialism. What if a race as technologically superior as the Europeans were to the Africans landed on Earth and set about behaving with the same disregard? And all the virtues of civilization, how long would they last? The protagonist is passive throughout, merely witnessing what the Martians do and then they come a cropper not because of any stratagem and bold resistance, but purely because they hadn’t taken their inoculation shots. The common British cold kills them off the way Malaria and cholera would do so in the colonies.

Here, that analogy doesn’t make as much sense, nor does it fit the mood. There’s no self-identification between the Martians and the Americans. The Americans identify the Martians immediately as terrorists – Robbie asks if they’re from Europe – but really they should be seen as Shock and Awe airstrikes and arrogant foreign meddling. Ray – being Tom Cruise has to be involved in some way in taking down a tripod or two – but his actions have nothing to do with the end of the invasion which occurs in the same way as in the book. Without the analogy of colonialism, the last act feels weak and something of a letdown. It also doesn’t make sense with one of Koepp’s key innovations on the story, that of having the tripods buried beneath the earth millions of years prior to the invasion. If they have been down all this time, and the aliens have the technology to have done all that, surely they had time to think about every possible danger including microbes and viruses. The whole journey has no real purpose as the danger has disappeared before the destination is met. The reunion with Robbie is a capper to this.

That said the film has some amazing set pieces and Spielberg’s visual storytelling is at its best. The initial attack, the ferry, and Ray running through a silhouetted forest while clothes drop from the sky: all take on power in his hands which elevates the material way above the usual action fare. But he is also channeling anxiety of the post-9/11 world. He isn’t going to be a happy cheerleader for Bush’s war on terror which has by this time already launched a highly contested war in Iraq. Nor does he seem comfortable criticizing his country in time of war – see the slightly cringe-worthy worship of the grunts in the last act. Uncertain and afraid, Spielberg shows an America where civilization is hanging by a thread. In some ways, Spielberg’s confusion is more revealing than the certainty expressed by others. It is closer to the mood of the country.

In his next film that confusion will once more be on display as he shed analogy and looks at terrorism head-on.