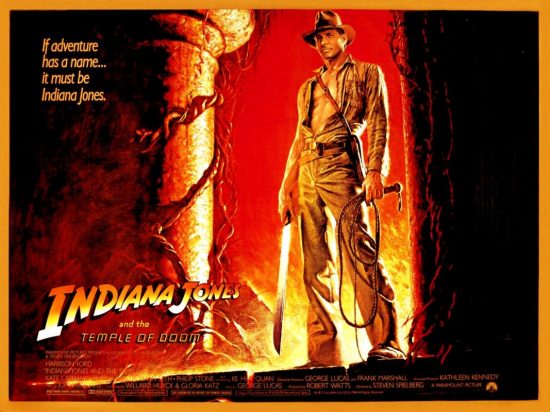

SpielBLOG: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom – A Steven Spielberg Retrospective

Indiana Jones came from a conversation that Steven Spielberg had with George Lucas on a beach in Hawaii. Everyone knows that. He was expressing his disappointment that he had been turned down for a gig making the next James Bond movie. The producers of Bond have always preferred a safe pair of hands who can be controlled rather than a talented director who might have their own ideas. But Lucas was nonplussed. Why would he want to waste his time on Bond? he wondered aloud. Lucas had a better idea for an action hero: Indiana Smith.

Indiana Smith was soon changed to Indiana Jones, but Steven Spielberg had apparently not forgotten his ambition of directing a 007 movie and the opening of the first sequel he would direct in his career gave him an excuse to go back to that initial wish with Harrison Ford resplendent in a white tuxedo. Add to this the Mandarin version of ‘Anything Goes’ complete with a Busby Berkley chorus number and Spielberg opens his new film deep in classic Hollywood territory.

Indiana Smith was soon changed to Indiana Jones, but Steven Spielberg had apparently not forgotten his ambition of directing a 007 movie and the opening of the first sequel he would direct in his career gave him an excuse to go back to that initial wish with Harrison Ford resplendent in a white tuxedo. Add to this the Mandarin version of ‘Anything Goes’ complete with a Busby Berkley chorus number and Spielberg opens his new film deep in classic Hollywood territory.

And it has to be said, the opening twenty minutes of the new adventure is a hilarious romp. The comedy is genuinely funny as the deal to recover a diamond from some Chinese gangsters goes wrong, poison is drunk, a sidekick murdered – the Chinese Detective David Yip with a beautifully camp death scene: ‘on this adventure I go first Indy!’ – and a nightclub reduced to mayhem. There are elements of the 1941 brawl here, as Indy sheds his suave panache, punching an unfortunate cigarette girl in the face in the midst of the chaos.

Kate Capshaw’s gold-digging nightclub singer Willie Scott is immediately established, as she attempts to grab the diamond too before accompanying Indy out of the window – via Vic Armstrong’s amazing stunt work – and into a car driven by Short Round, played by Ke Huy Quan who would also appear in The Goonies. From frying pan to fire, the film is closer to the spirit of the Saturday matinee series that inspired the character than the first film. Whereas Raiders was essentially grounded – the Nazis help – Temple of Doom throws itself all in for literal cliffhangers and ludicrous twists. When our trio of heroes jump out of an airplane in flight with just a life raft to make do as a makeshift parachute, we know that we’re not going to have to suspend our disbelief so much as send it to Mars in a rocket ship.

As well as the gee-whiz adventures and screwball comedy team of Capshaw, Ford and Quan, unfortunately Lucas and Spielberg also cart over an unexamined 1930s casual racism, often played for comic effect. The most infamous sequence is probably the ‘chilled monkey brains’ scene, but throughout the whole film there is a totally unreconstructed delivery of British imperial racial theory. Both Lucas and Spielberg have form on clumsy racial humor and stereotyping, though Lucas is the most obvious repeat offender, with his conniving Orientals and Jewish slave owner in The Phantom Menace. Personally, I find the banquet very funny. It’s so over the top that it is almost like a cartoon. I imagine if I was of Indian descent and living in the US or Britain in the 1980s, I might have been much less sanguine.

The idea of the Thugee cult is more problematic, especially with the Prime Minister, played by Roshan Seth (later BBC’s Buddha of Suburbia), first appearing thoroughly westernized and then deviously also a member of the cult. You can take the boy out of Thugee, but you can’t etc. Admittedly, Indiana Jones contributes another version of the ‘white saviour narrative’, and Spielberg makes no attempt to mitigate images of him being worshipped by the villagers as he returns the children from the mines.

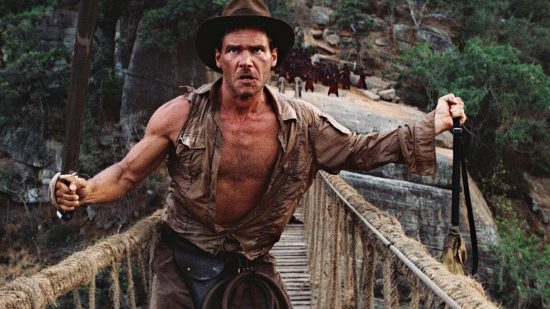

When I first saw the film in the Summer of 1984, none of these criticisms occurred to me. I was young and it was my birthday. As I write this it’s my birthday again tomorrow. These things seem to happen annually. One thing my twelve-year-old brain was baffled by temporarily was the fact that Temple of Doom wasn’t a sequel but actually a prequel. It was disconcerting but also a good idea. This wasn’t a continuation and although there were callbacks to the original film – the sword duel resolved by pistol joke for instance – the film is determined to be different. Lucas saw it as being the dark middle chapter much as Empire had served in the original Star Wars trilogy: Indiana Jones Goes to Hell. Having Indy turn evil – even temporarily – was a shock. Spielberg stretches himself with some broad comedy, the quickfire dialogue and loving pastiches. Pauline Kael would call the film: ‘One of the most sheerly pleasurable physical comedies ever made’. From literal cliffhangers, the film ends up being a literal rollercoaster ride. Don’t peer too closely at the miniature work, but I’d still rather the Indy doll chase than the usually CGI heft free nonsense that dominates the last act of most blockbusters these days. And then we get to the rope bridge.

Also, the film had another effect, essentially inventing the PG rating as the heart excavating gore proved too much for the censors. Spielberg had always pushed the envelope with gore – the severed leg of Jaws or the melting heads of Raiders – but here he seemed determined to push it as far as he could and instead of pushing back, the powers that be simply invented another category. Indiana Jones was a children’s film for grown-up children.

Also, the film had another effect, essentially inventing the PG rating as the heart excavating gore proved too much for the censors. Spielberg had always pushed the envelope with gore – the severed leg of Jaws or the melting heads of Raiders – but here he seemed determined to push it as far as he could and instead of pushing back, the powers that be simply invented another category. Indiana Jones was a children’s film for grown-up children.

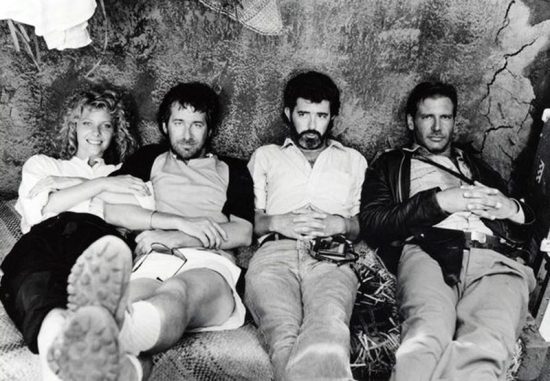

Not everyone loved the film. The general consensus was that it was okay but not on par with the original. Spielberg himself felt it was the worst of the original Indiana Jones trilogy, believing the best thing to come out of it was his marriage to Kate Capshaw.

But I actually like the film a lot. I included it in a round up of Spielberg’s most under-rated movies for The Skinny. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom works as a comedy with many more laugh-out-loud moments than the original, including the one that inspired the gif on this page. Spielberg, however, had probably had enough of franchises following the tragedy of Twilight Zone and the underwhelmed reception of the second Indy instalment. He was ready to settle the nagging doubt that he was anything other than a director of hugely successful popcorn movies. He was about to pick a subject that would take him – he hoped – into a different league.