Review: The Accountant of Auschwitz

Directed by Matthew Shoychet.

The Nuremberg Trials, which put many Nazis in the court for crimes against humanity, took place some three quarters of a century ago now, but the echoes of those trials, of the legal precedents they tried to establish (that those who committed horrendous crimes like genocide would be held accountable) and the vile deeds they sought to punish have echoed down through the twentieth and twenty-first century, as we’ve seen more and more genocidal slaughters such as Rwanda or the murderous “ethnic cleansing” in the former Yugoslavia (and the trials in the Hague that followed years later). When it comes to the almost unbelievable crimes of the Holocaust though, we are very nearly out of the range of living memory, fewer and fewer who were there (survivors or perpetrators) are with us each year.

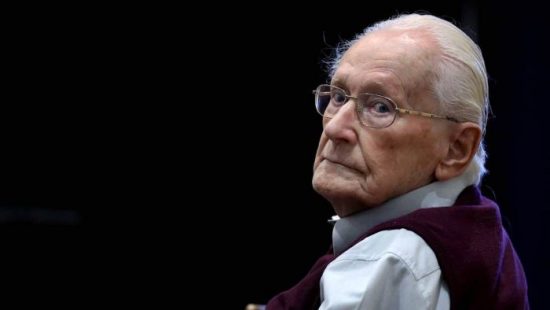

As such it becomes all the more important that we have documentaries like the Accountant of Auschwitz, which records events around what may well be one of the last such trials of a Nazi for crimes committed during the Second World War, in this case a seemingly normal, frail old man, Oskar Gröning, the eponymous accountant. Looking at footage of this 94-year old man it is hard to picture him as the young man he once was, more than seventy years ago, let alone as a black-garbed officer of the SS working in one of the notorious death camps (one commentator noted seeing such a frail old man enter the court she felt sympathy. But then she recalled what he and his comrades had done, and that sympathy evaporated). But he did, and after a long, long time, justice finally reached out for Gröning.

“Hate is a powerful weapon. And it was in the Second World War and it is today,”

“Hate is a powerful weapon. And it was in the Second World War and it is today,”

Rainer Höss, anti-fascist activist and grandson of Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz told the film-makers, adding that the trial was important, not just to try and enact even belated justice, but to remind the newer generations of the horrors that went before and can happen again far too easily (we only need to look at the appalling rise in hate crimes in many countries to see how easily we can start down that road again). Höss also remarked that Gröning’s trial was important because it heard a lot of testimony not just from survivors of the camps, but from the perpetrator. When we have groups who willfully ignore the huge amount of evidence and still try to claim there was no Holocaust, or that it was exaggerated, the importance of this becomes clear, and some credit must be given to Gröning himself who makes clear that yes, these things did happen, he was there in his SS uniform. And if he says that it is just that bit harder for the modern neo-Nazis to continue their Holocaust denial.

The film doesn’t just focus on this one trial, however, it attempts to place the proceedings into a much longer sequence of events, from the post-war Nuremberg trials to the quite shameful blind eye the new, post-war West German government turned to the many former Nazis who were allowed to go free and live a good life (indeed many ended up in charge of government, industry, the judiciary, so became the class that sets the rules and laws for such investigations and trials), and how the way the law was worded only allowed for very specific, hard to prove charges to be brought (such as a specific act of a specific person killing another during the Holocaust), which allowed many to escape any consequences for their actions.

There was also some element of collective guilt – how many fathers, uncles and grandfathers took part in these events? How much guilt by association does that create for the rest of the country trying to move on and rebuild? The few trials that did happen in Germany rarely convicted and those that did often gave remarkably lenient sentences (a soldier responsible for putting the Zyklon B gas into the fake shower rooms to gas victims to death got only three years). The Demjanjuk case, which some of you may remember from the news some years ago, helped to bring a change in the attitude in Germany. He was found guilty in an Israeli court where witnesses were sure he was “Ivan the Terrible”, but records found after the fall of the Berlin Wall revealed that he was not (although it transpired he had much other guilt, which he pretended ill-health to try and avoid answering for). Laws were altered to allow for trials that relied on more data and less on witness testimony (which had proven so unreliable in his case), and for those who may not have killed personally but were there supporting the whole process to also be held liable (such as Gröning, who rifled the belongings of those marked for death for valuables).

D-Day veteran Benjamin Ferencz is also interviewed – Ferencz was one of the chief prosecutors of the notorious Einsatzgruppen at the Nuremberg trials. They knew they could never hold every single person who contributed to the death camps to account – they numbered in the tens and hundreds of thousands, they would still be holding trials today, as Ferencz put it. Instead, his idea was that they would set a legal precedent with the trials, to show that any country that committed such horrible acts would, sooner or later, be brought to justice and individuals responsible would face trial and judgement. The idea was not just to punish these vile crimes but to put fear into future evil-doers that they would always, sooner or later, be brought to account for their disgusting, inhuman actions (think of the vile Ratko Mladić finally brought to trial in the Hague).

“Vengeance is not our goal, nor do we seek merely a just retribution. We ask this court to affirm, by international penal action, man’s right to live in peace and dignity. “

Ferencz spoke these words at the opening of the Nuremberg trials, and the film-makers cut between this now frail, elderly but still strongly motivated man discussing his role and starting to recite his opening speech, which cuts to the archive footage of him in the courtroom in the 1940s, a nice touch. Alan Dershowitz, a former special prosecutor at the US Department of Justice who was involved in modern trials of historic war criminals, also gives some legal, historical and moral context to the trial of Gröning.

The trial itself is fascinating but also, as you can imagine, disturbing – some testimony is beyond comprehension, such as the cold-blooded murder of an infant in front of the mother, something Gröning witnessed a comrade do. I imagine most viewers will realise these horrific details are unavoidable, given the subject matter, but as with the powerful Night Must Fall documentary a couple of years ago, despite that I still commend viewing to people, because, dammit, we’re still seeing the sort of raw hatred of those judged to be “different” and where it leads, and we really, really need to be reminded of it, to learn from it. The testimony of those who were there, whose ranks thin further each year, is vital, but also the film’s placing the events and their impact into legal and moral context for modern society, and, importantly, for future generations (and possible future perpetrators of such horrors) is extremely important, not only in making sense of it all, but in reminding us that we all, collectively, have to try to learn, to be better, and if and when some of us fail that others can and will deliver justice on them.

The Accountant of Auschwitz is released on DVD and Digital by Signature Entertainment from Monday 15th April.