Review: Fassbinder’s World on a Wire (Welt am Draht) – “A remarkable piece of German film and science fiction history”

Directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Starring Klaus Löwitsch, Barbara Valentin, Mascha Rabben, Karl Heinz Vosgerau, Wolfgang Schenck

“The world in a nutshell…”

Here’s a remarkably unusual 1973 film by famous (and often infamous to some) film-maker Fassbinder, an intriguing slice of science fiction that’s very much ahead of its time. Based on the novel Simulacron-3 by Daniel F. Galouye, this German language film (originally made for television and shown in two parts), a production I’ve heard mention in discussions about science fiction history, but never seen. World on a Wire (Welt am Draht, to give it its original title). The German government (or the West German government as it would have been back then) funds a cybernetics research programme which has developed a next-generation computer, which they intend to use to model events and trends in society.

That may sound fairly normal to our modern-day sensibilities, given organisations and governments have used detailed data on computers to run predictions, trends and modelling to help predict what resources may be required in the future – are birth trends indicating we will need more schools and teachers in a few years, for instance. Simulacron, however, is indeed some next-generation level modelling – this computer has created a virtual world, a small town of around ten thousand digital inhabitants (“identity units” as the programmers refer to them), all effectively living their lives, the programmers able to observe them, tweak their personalities and world. Modelling the real world, combined with some unusual anthropology.

The programme is a high priority for the government, but hits a stumbling block when the main creator, Vollmer, dies in mysterious circumstances (is it an accident or something more sinister?), his friend Dr Stiller (Klaus Löwitsch) is asked to take over the project, reluctant at first but soon persuaded by the oily Siskins (Karl Heinz Vosgerau). It’s just the start of his problems though – a a party hosted by Siskins his friend Günther Lause (Ivan Desny), the head of the project’s security vanishes, just after talking to Stiller about his misgivings about Vollmer’s death not being an accident. And I mean vanishes – one minute he is there in a chair in the middle of the crowded room at the party, Stiller turns away for something, turns back and he is gone.

It becomes increasingly peculiar after this – Stiller reports Lause’s disappearance to the company and the police, but only a few days later nobody even remember the man existed, and he is introduced to another man who is the head of security, and has been for years. Even the police detective he reported it to has no memory of Lause or of Stiller telling him of his disappearance. His regular secretary takes ill and is moved away, to be replaced by a new assistant appointed by Siskins, played by Barbara Valentin (one time paramour of Freddie Mercury), and he can’t help but feel despite her being very friendly to him, that she is perhaps there to keep an eye on him.

As he continues to investigate the death and disappearance while working on the Simulacron project, Stiller becomes increasingly agitated and disturbed – he has himself linked into the simulation, effectively riding one of the virtual people’s lives, to observe, but while there the entire street blanks out on him several times. A glitch or something else? A colleague discusses the “reality” of the virtual lives lived in the simulation, commenting on how Vollmer spent so long programming every aspect of humanity into them, wondering if it could create something akin to actual consciousness. And then he finds a record of Lause – not by name in the database, but by searching through descriptions, there he is in the Simulacron database, programmed by the deceased Vollmer himself.

This is a real slow-build into a series of increasingly disturbing concepts (it’s over three hours, you can see why it aired over two evenings, originally!) – Stiller starts to lose his grip on what reality could be. Is he the puppet master, the god of this virtual construction and the digital lives within, or is he another puppet, but a puppet who is starting to see some of the strings? Is he even real? He is so sure at the beginning that he is in the real world, crafting Simulacron, but as the discrepancies pile up he starts to wonder if the digital beings from Simulacron are somehow crossing over to the real world, taking over the bodies of the programmers who enter the simulation. Or is it even more complex, can he be sure he is the one running the simulation? What if he himself is in a simulation (and running a simulation?). It sounds like psychotic delusion, but really, how do any of us know, much less prove, that the world we see around us is real?

Bear in mind this is some three decades before the Matrix introduced the wider cinematic audience to concepts like this, this is pretty high concept for 1973, and really it’s still high concept today, in my opinion, because it is a great piece of drama laced with philosophy, and that philosophical question about the nature of reality and perception is, as the Matrix and others have shown, still one which perplexes us to this day, and is the subject of scientific debate too as our computing abilities become ever more powerful, it is a legitimate question to consider if a more advanced species could be running what we perceive as the real world and our lives as a vast simulation. How would we know? Imagine if that thought got into your head as it does with Stiller, how would it affect you? Would anything matter anymore if you thought none of it was real?

“I can’t be alone in thinking nothing really exists.”

While the concepts are both disturbing and perplexing, the visuals are highly stylised – many of the actors move in a very unnatural manner, posed in scenes almost like carefully arranged mannequins in a display, many conversations are shot with one actor reflected in a shiny surface or through a distorted lens, scenes are framed in non-realistic ways (one actor on top of the stairs talks to someone below rather than walk down to talk to them as you’d expect). At first I thought this was mostly Fassbinder choosing a deliberate, non-natural style of acting and framing for his cast, but as the film goes on I started to feel perhaps it wasn’t just a style but a deliberate move to create a feeling of wrongness, that the people and places simply aren’t quite real, and it does add to the increasing sense of disconnection and confusion Stiller is experiencing.

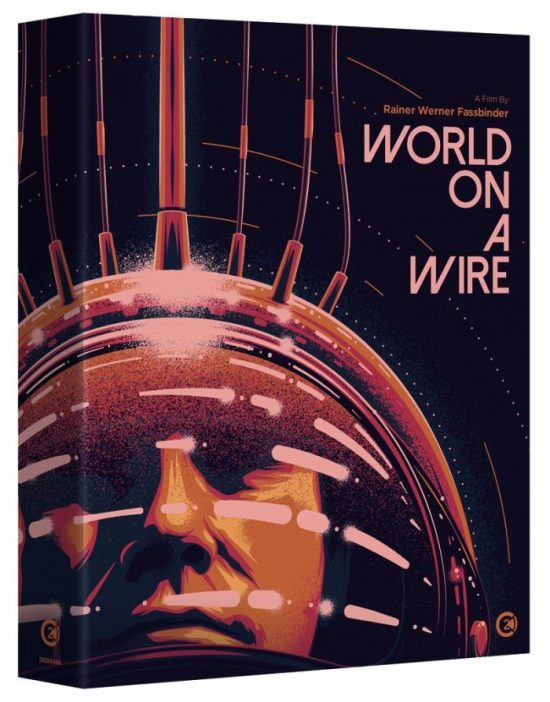

This is a very unusual, thought-heavy slice of 70s science fiction, and while the look – many of the offices are designed to look ultra-modern, except what was ultra-modern in 1973 looks unbelievably kitschy and dated now – has not aged well, the concepts and the depiction of a man losing his grip on reality, and perhaps even discovering that there is no reality, remains very powerful and compelling, even in our post-Matrix world (the film even boasts a scene where Stiller exits Simulacron via a phone booth – sound familiar??). Here is a remarkable piece of German film and science fiction history by a major cinematic figure, lovingly restored by Second Sight, collaborating with the Fassbinder Foundation, and being issued in a limited edition packed with extras (featurettes, interviews, documentary, booklet and more), this has clearly been designed for the serious lover of cinema.

The limited edition Blu-Ray of World on a Wire is released on February 18th.