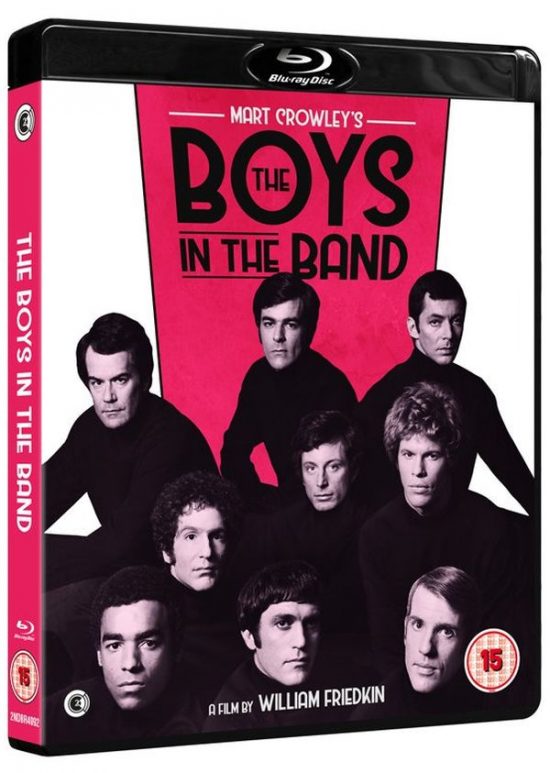

Review: The Boys in the Band – “A delight of sharp-toothed wit”

Directed by William Friedkin

Starring Kenneth Nelson, Robert La Tourneaux, Frederick Combs, Cliff Gorman, Laurence Luckinbill, Keith Prentice, Peter White, Reuben Greene, Leonard Frey

“If there’s one thing I’m not ready for it’s five screaming queens singing ‘happy birthday’.”

Here’s an unusual slice of cinematic history for film fans: an early work from a director who would go on to be one of the major American helmers, William Friedkin (The French Connection, The Exorcist). The Boys in the Band also stands out as one of the first mainstream movies about gay culture, with an all-gay cast of actors, still not exactly a regular occurrence today, remarkable for 1970. Adapted from Mart Crowley’s hit Broadway play (Crowley adapted it for a screenplay himself), it also boasts the original stage cast. The film was, unsurprisingly, controversial at the time (and since), not just with more conservative audiences uncomfortable with gay culture being so openly displayed, it also split some of the gay community, with some angry at the way it portrayed gay men, others were delighted to see gay lives being portrayed on the big screen.

The plot revolves around a birthday party for Harold, one of a circle of friends, all gay men in New York, with Michael (Kenneth Nelson) setting up his apartment for the party and welcoming his other friends who arrive one by one. Birthday boy Harold is the last to arrive, fashionably late (one can’t help but feel deliberately so, especially given his prickly character), and a good bit of the running time actually passes with the friends exchanging gossip and small talk, mixed with barbed comments, until he arrives. Despite being a circle of friends it is clear there are a lot of cracks and a lot of tension in this group too, and those are heightened by Michael’s straight friend Alan appearing during the party (he has known Michael since college and doesn’t know – or claims not to know – that Michael is gay).

And Harold arrives. Harold the thirty-something gay Jewish man in his green velvet suit and tinted glasses, a tongue barbed like a rose bush and with a dry, often cruel wit that’s like Oscar Wilde lines shaped into a rapier, perhaps the one person in the group who has an even sharper (and oft-times nastier) wit than Michael, and he takes savage delight in reminding him of that fact as the evening progresses. The party passes through stages rapidly, from a happy period as they prepare for the evening (comments are exchanged, but they feel like banter rather than nasty at this stage), then it starts to become uncomfortable with Alan’s arrival, then when Harold appears the comments become sharper, nastier, confessions come, arguments, secrets revealed.

In many ways the film shows its theatrical roots – the vast bulk of it is all set in Michael’s apartment, and you can see how that worked well for a stage performance. The thing is that apartment is essentially a crucible in which the different friends and their simmering passions and resentments can come to the boil, there is no need to open it out to other locations that cinema can use, and it is to Friedkin’s credit that he understands this and resists any attempt to insert unnecessary settings or imagery, he shoots around the apartment and the cast, putting us right in there with them.

It can be argued that despite the all-gay cast the film (and play) suffer from having too many stereotypes (the sashaying overly effeminate one, the straight-acting one, the super promiscuous one, the gorgeous but dumb one etc), and while there is some truth to this, as Mark Gatiss notes in one of the disc’s extras this was one of the first times these types were shown so prominently in mainstream cinema (Gatiss is interviewed in the extras as he is acting in a revival of the play), and as he further points out, those characters aren’t claiming to represent every different kind of gay person, but they do make a good selection to try and shine a light into a group that hadn’t been featured much outside of underground cinema till then. And of course this pre-dates the awful horror of the AIDS crisis a decade or so later, and even pre-dates the events of Stonewall, and we have to take it in that context.

Those barbed one-liners and comments are one of the jewel’s of Crowley’s script, they flow pretty much from the start – Michael showing Donald to the guest room, pointing out he got him his own toothbrush as he’s sick of Donald borrowing his. “How do you think I feel?” retorts Donald. “Oh, you’ve had worse things than that in your mouth…,” replies Michael, archly. Or Michael commenting about “tired fairies” and “screaming queens” at the party night, Donald asks good-humouredly “Are you calling me a screaming queen of a tired fairy?” “Oh I beg your pardon, there will be six tired screaming fairy queens and one anxious queer,” responds Michael.

The lines just keep flowing like that and had me smiling and laughing at their tartness, but as the party goes on the comments become increasingly cutting and painful, it almost seems like they hate each other (in one very emotional scene Michael sobs that they have to learn to stop hating themselves so much), and yet… And yet there is far more going on here; while those vicious, bitchy lines escalate from nasty barbs to poisonous harpoons there is also a feeling that they are all still connected, still friends, that they need each other, that they can only be this dysfunctional around each other in a way they can’t in the rest of society (and isn’t that the case with many of us and our friends? Only around them can we really be that vulnerable or wrong-headed and yet still be accepted). Each of them exposes their weaknesses and wishes, and for me, that took them past any “stereotyping” and made them real people that I could emote with and empathise with.

This is a delight of sharp-toothed wit, a rare early mainstream cinematic exploration of queer culture and lives, and an important entry on the film-roll of a major director (Friedkin says that it is one of his films he is still very proud of), and for all those reasons it’s great that Second Sight is bringing it back to film lovers. You’ll find yourself saving some of those biting one-liners to use yourself at some point.

The Boys in the Band is released by Second Sight on Blu-Ray (with a bunch of extras, including the aforementioned Mark Gatiss interview, and commentary from Friedkin and Crowley), on February 11th.