Roadshow: The Making of The Cinema Travellers

Trevor Hogg chats with Shirley Abraham and Amit Madheshiya the importance of movies in India and the challenges to produce the documentary The Cinema Travellers…

Upon graduating from college in media and communications, Shirley Abraham and Amit Madheshiya heard people around them lamenting about the rise of theatrical multiplexes and the demise of travelling cinemas where audiences sat in a tent with a film projector and screen; they were curious to learn whether the situation was the same in rural areas and led them on an eight-year odyssey that concluded with the release of their debut feature length documentary The Cinema Travellers. We travelled to Maharashtra which is in the backyard of where we live in Mumba and found that these travelling cinemas had existed for about 70 years,” explains Abraham. “However, there was no account of these in the evolution of cinema history in our country. We had to do something about this.”

The photographic style is like a stationary camera at a distance waiting for things to happen. “It’s a distant gaze for the long while and then suddenly we jump into the close-up; that really sets the grammar of this film,” notes Abraham. “There’s a sense of anticipation that the movie is coming but has yet to come. We’re looking at the film being threaded and the projector’s hands are trembling because he’s under such tremendous pressure.” The opening sequence was a struggle to get right. “It took us one month to cut that scene as we’re not trained editors,” remarks Madheshiya. We finally arrived with the idea of throwing you into the middle of that and then taking a broader look of what this world is like.”

A montage of stills was incorporated into the footage. “I am a photographer and shot those before we started making the film,” explains Madheshiya. “They encapsulated the magic, wonderment and enchantment of cinema. It’s also speaks a universal language. It’s not India-centric. People across the world watch movies like that whatever setting they’re in.” The documentary needed to be restructured to prevent the stills from bringing the narrative to a halt. “We had to look at what the film was saying so the photographs could also be a part of it,” remarks Abraham. It’s like a magical realist landscape that you’ve built and these photographs become something that stop time. It’s a place of reflection.”

No narration takes place. “It was the most difficult thing to do and is partly the reason why it took us so long,” states Abraham. “When you put a voice over or add text things become much easier. You can explain so many things and move on. But we wanted to make a film that was driven by its own people. I didn’t want my presence to be felt.” Three different storylines drive the narrative. “For Mohammed this is his livelihood; he wants to do business today. For Bapu, it’s about the legacy he’s leaving for the children because the village is not coming to the cinema. Prakash is a projectionist mechanic who lies in the curious space because he’s in the past but also looking at a future where machines continue to be a part of his life.”

Trust was earned over time by the filmmakers when dealing with travelling cinema community. “We spent three years research and another five making the film so that’s eight years,” remarks Abraham. “At some point we became a part of it. We were with them in their tents, trucks and projection booths. We didn’t remain variables to them anymore. They weren’t reacting to us. There is also this fluidity of interaction in the film. They speak to us at times but it’s not a performance for the camera.” A single Canon 5D camera with a 24-70mm lens captured the footage. “It helped that the Canon 5D is a small camera,” states Madheshiya. “We all perform for cameras but after a while you’re so absorbed in your life and the intensity of the moment that you’re not really aware of what the camera is capturing.”

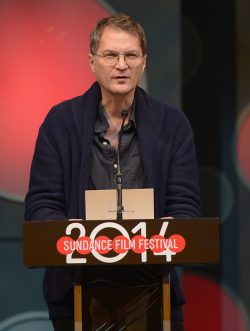

Most of The Cinema Travellers was shot with natural light by Madheshiya. “Just once or twice in the film I used a tungsten bulb which was also part of the setting.” The only time there was a division of work between the cinematic duo was out on the field. “I would usually be the director and Amit would be the camera person because that’s when it gets intense when people are doing everything,” remarks Abraham. For the longest time there was no funding because when we would pitch the idea people would say, ‘You’re trying to make an art instillation. There’s no money for such things. It’s not a documentary. What is the issue? Where is the poverty?’ Eventually we made a trailer and the Sundance Institute saw it. They were supportive through their funding programs and labs; that was crucial to the making of the film.”

A key mentor was editor Jonathan Oppenheim (Paris is Burning). “Jonathan was our consulting editor and we learned so much from him,” enthuses Madheshiya. “He’s the one who showed us the path. I wish there was more physical interaction with him because he was based in New York City and we were in Bombay. We spoke on Skype.” A couple of trips were made to New York City. “Early on Jonathan pushed us to look at these three people having different value systems,” remarks Abraham. “He kept reminding us of why we had chosen them. The awareness of why you’re choosing these people dies out because you’re so absorbed in the mechanics of it. Jonathan insisted that subconsciously you have to hold onto that reason.”

Skywalker Sound was the site of the final audio courtesy of the Sundance Institute. “We met Pete Horner at the lab and he was a great collaborator,” remarks Madheshiya. “He has worked with Walter Murch [ ] who is my guru.” Pete Horner does a lot of independent and big films like Jurassic World. He’s somebody who works with the director and the music composer because that’s his ideology. Pete believes that these are three important pillars of a film. We all need to work together in close collaboration months before mixing the sound. That was something that he pushed us towards. Eventually we came close to that ideal. Other Sundance Institute mentors were composers Laura Karpman and Nora Kroll-Rosenbaum. “Laura has this amazing view of things,” states Abraham. “With all of this back and forth we arrived with something that felt like it belonged to India but also had an international feeling.”

Being inexperience filmmakers was the biggest challenge. “What I learned is that inexperience makes you fearless,” notes Abraham. “I learned that we all have a certain nostalgia for the past but there are people who are looking at the future while learning from the past. Prakash is somebody who continues to apply that knowledge and wisdom into something which is propelling him constantly. That was inspiring for me. It happened after the movie but some thieves broke into his shop and stole everything that he had. I was talking to him after that and asked, ‘What are you going to do now?’ Prakash said, ‘I’ll make them again.’ He’s 70 years old. That is something that I hold extremely close to my heart.” Madheshiya learnt how powerful cinema can be. “The tent is burning inside and people are sitting on rocks watching films. They had travelled from far and waited the whole day. It was difficult for us to stay for the whole run of the film because you’re sweating like pigs. People are sitting and watching the film and completely enjoying it.”

“I’m fond of the cave scene because that embodies what this film is about,” reveals Abraham. “It’s about how cinema is so new and there are these cave paintings that have existed for so long. Back then they had no machines and now we wonder how they did them. That’s what is happening to celluloid cinema.” Madheshiya does not have a parental attachment to the project. “I don’t see it as a child. I’d rather see it like Jonathan. It’s a Frankenstein monster. We have tested and it’s speaking a language. The monster is ours now. For the longest time Jonathan said that your monster is not speaking. He would keep pushing us. Then finally he told us that your monster is talking now. Then we knew that the film was ready to be sent out into the world.”

Many thanks to Shirley Abraham and Amit Madheshiya for taking the time to be interviewed.

Trevor Hogg is a freelance video editor and writer who currently resides in Canada; he can be found at LinkedIn.