EIFF Review: McLaren Animation screenings – Facing It, Inanimate, Double Portrait and more

I always make a special point of attending the two McLaren short animation strands at the Edinburgh International Film Festival each year. BBC2 and Channel 4 used to have animation seasons, but that’s something that seems to have fallen mostly by the wayside these days (despite each now having multiple digital channels) and the days of a wee short before the feature film in cinemas is long gone, which, for me anyway, makes it more important to support and celebrate when we get to see short animation being highlighted, especially when it is being shown on a cinema screen. We have some remarkable young animation talent in the UK, and this and other festivals are a chance for them to shine, to effectively show their portfolio in order to try and secure more work (be it with an animation house on a film or the bread and butter of music videos, ads etc which help pay the bills) or compete for scarce funding.

Inaugurated in 1990, one of the pillars of EIFF’s awards is the McLaren Award for Best British Animation, named after Scottish born animation pioneer Norman McLaren.

Each year the McLarens always impress me with the range of material on offer, both in terms of method (from slick CG animation to traditional hand-drawn or stop-motion work and all sorts in-between), and subject matter (some are funny, some are political, some are biographical, some bring a lump to the throat). This year was no exception. Given the two screenings took in over twenty short works I am not going to go into each and everyone that was shown, but I will pick out some of those that made an impact on me, personally.

Sam Gainsborough’s Facing It was a pretty unusual-looking piece, mixing live action actors with claymation faces overlayed on their heads, producing a strong visual style for the piece. A young man waits for others at a table in a busy pub; he clearly wishes to reach out and be a part of the buzz of vibrant, lively conversation and life going on all around him, some even invite him to join them, but his crippling shyness halts him, his claymation face morphing, a hand literally growing out of it to clamp around his mouth as he tries to speak to a stranger, while flashbacks show childhood events with his parents which shaped this isolation and nervousness. While most of us don’t suffer from such an extreme I think we have all had moments where we need to interact with strangers or a group and have that anxiety moment before we do. The plasticine animated faces over the live actors works very well, allowing for a range of emotional expression way beyond what even the most facially gifted actor could give; it’s a lovely example of one of those things animation can do so well, using a few simple visual signifiers to show the internal emotions of a character so clearly.

FACING IT – TEASER TRAILER from Sam Gainsborough on Vimeo.

Ian Bruce’s Double Portrait splits the screen into two hand-painted images, changing and coming to life before our eyes, telling the story of a woman, Geraldine, and her first love, of how it all seems so straightforward to them when younger, but how life changed them, parted them, brought them together again. It’s beautifully illustrated with Bruce’s painting, giving a warm feel as we move through their lives across the decades. Jonathan Hodgson’s Roughhouse, a traditionally-drawn animation, tells of a group of pals, friends since childhood, marked by a moment of rough play with a pet that ended badly, later growing up, going away to college, meeting a new flat-mate and settling into student life (complete with messy flat). It’s actually quite a brave film, I think – Hodgson gives us characters who are often not very likeable, and the roughest of them all, the one who never pitches in for the rent but can always pay for drink, seems the least likeable of the group, but Hodgson carefully shows us that under laddish, unthinking jokes and “banter” and bravado there are feelings and even the seemingly strongest and toughest can suddenly crack. It’s a good reminder that under it all everyone is human.

Roughhouse Trailer from Jonathan Hodgson on Vimeo.

Maryam Mohajer’s Red Dress. No Straps draws on some of her Iranian background, with a very young girl living during the era of the Iranian revolution and the awful Iran-Iraq war which lead to scenes reminiscent of the First World War. At home with her grandparents, grandma indulging her beloved grand-daughter by making her a dress like her favourite US pop star seen in a magazine (that has to be hidden from the religious authorities who are busy teaching her and other kids to shout “death to America” each day at school). A red dress, strapless. Meanwhile, they have to worry about bombing raids on civilian targets during the war, but she tells us Saddam is not very good at this and they are all okay. It’s a lovely, warm piece evoking a strong feeling of family that any of us can identify with, but despite what she says, everything is not okay, and this is a film that left me with a lump in my throat.

Red dress. No straps. trailer from maryam mohajer on Vimeo.

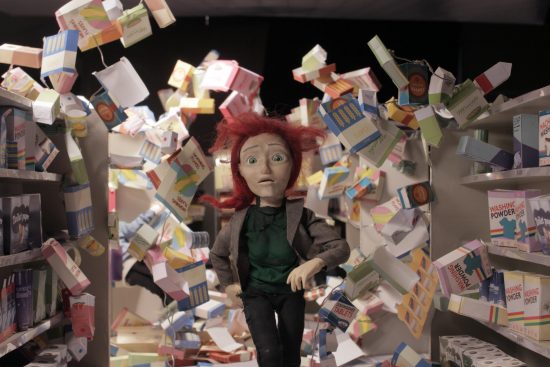

Lucia Bulgheroni’s Inanimate proved to be my favourite of all the films shown in both McLaren screenings. I love all form of animation, but I have a special soft spot for traditional stop-motion animation. There’s something for me that is truly magical about knowing that everything you see on the screen there has been built by hand, from the characters and their clothes to the tiny sets, furniture, right down to coffee cups, then, through a painstaking alchemy, enchanted into life, one frame at a time, hours, sometimes days to capture a few brief seconds of movement. In Inanimate Katrine is leading her normal life – work, home, shopping, boyfriend. And then things seem to go wrong, to be disconnected, she is doing one thing and suddenly, whoosh, she’s rushed from home and finds herself at work with no in-between, then somewhere else and somewhere else. She panics, is she losing her mind, having blackouts?

And then she starts to see the world around her differently, it starts to seem unreal to her, and soon so do the people and then, most terrifyingly, her own body. Her skin looks fake, it peels back and she sees the metal armature of a stop-motion puppet below. She isn’t real. Around her she is suddenly aware of a huge figure, flickering at a speed that leaves them almost invisible, changing things around her world and other little worlds nearby. She’s a puppet who has somehow become aware, seen behind the scenes of her little reality, seen the strings and the puppet master. It’s both a story about how we all invent our own little realities to cope, to understand, to get through life, but are often aware there is more, just beyond the edge of our vision, and at the same time it is an ode to the laborious art of stop-motion, those long, long hours to create tiny moments of life in inanimate objects are, from her point of view, fleetingly fast.

It reminded me of Tom Moody at the McLarens a couple of years back, talking about working with found objects which he turns into characters, then brings to life with stop-motion. Tom talked about the sadness which went with the joy of animation, joy at making something, but the sadness that after all the care to bring these creations to life they only had those few, brief moments of that life, then they would go on the shelves with older creations, never to move again, a rapid, Mayfly experience of the world. I suppose there’s probably a lesson about life in there, somewhere.

Space doesn’t really permit me to go into all the other works, but I must mention Sinem Vardarli and Luca Schenato’s (very long-titled!) The Brave Heart or (The Day we Enabled the Sleepwalking Protocol), which, like the old Numbskulls Brit comic or Pixar’s Inside Out it took us inside the body, with various organs such as the Heart and Brain, carrying out their tasks (or not), in the face of a booze, smoking and fast food blow out (very clever, very funny and rather dirty, especially when this all leads to an emergency “blockage” which I shall not describe here!). Stephanie Hunt’s Marfa took us around an odd wee Texas town, from local bands to local characters and gave a lovely flavour of life in a remote small town.

“The brave Heart” or ( The day we enabled the sleepwalking protocol ) Trailer from Luca&Sinem on Vimeo.

Ben Steer’s Mamoon had a mother and child, shadow figures projected onto polystyrene buildings, pursued by dark shadows – as the light fades so too do the shadows which it projects, which means doom, and the shadow figure mother desperately tries to save her child, while Daniel Prince’s Invaders uses very polished CG animation to bring to life three tiny flying saucers, exploring a human home on Christmas Eve, the smaller one unsure of his place with the larger two, trying to prove himself. There was a strong 80s vibe to Invaders, I thought, and Prince confirmed this in the subsequent Q&A, noting 80s Spielberg and most notably Batteries Not Included as influences. Simon P Biggs’ Widdershins was a delightful tale of a Steampunk, quasi-Victorian future of clockwork and steam automata making everything so perfect our character can’t stand it anymore and falls for a daring young woman who challenges the system. I also loved it because “widdershins” is such a lovely word and we rarely get to use it…

Mamoon Teaser from Blue Zoo on Vimeo.

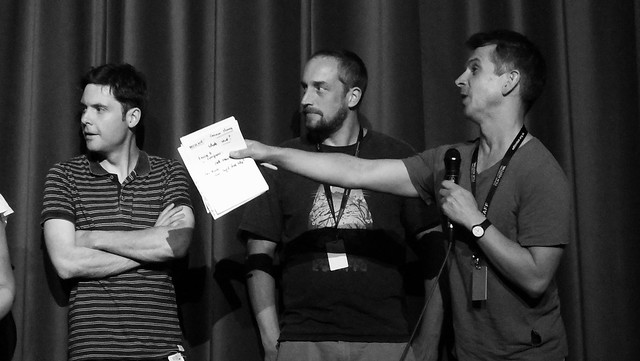

In the post-screening Q&As with a number of the animators one of the subjects raised was trying to get funding for short film work, and how much harder it had become. Adding to that, as to many other projects, was the looming spectre of Brexit. The animation director for the festival spoke about manning the British stall at the famous Annecy Animation Festival and remarked it was “tumbleweed” for them. With so much uncertainty nobody wanted to invest in UK productions or take on distribution. In fact he commented that those from outside Europe were being more actively courted by European partners than the UK team. Jonathan Hodgson told us how he could not get any funding from any UK company or arts organisation, but eventually a French one did agree to help, and he, like others, wondered if that avenue was now being closed to them, a question many in various arts disciplines (and science and business) are asking? This is not the place for a political discussion, of course, but equally it would be remiss not to note the worry of film-makers and others about how opportunities for co-operation, distribution and funding for their future work will be affected, and at the moment none of them has any real answers as to how they will be affected, and I’m sure that is a worry being discussed across the UK film industry.

(some of the animators doing Q&A sessions in the Filmhouse, post screening of this year’s McLaren Animation strands at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, pics from my Flickr)

It was another great crop of inventive, often emotional, sometimes funny, sometimes touching short film-making by all sorts of different women and men working in different methods and styles to bring still objects and art into flickering life. Often I will see some of the McLaren animators figure months later in the short animation categories for BAFTA and Oscar, and fingers crossed some from this year’s crop will have that success too. Props again to the film festival for continuing to support the McLarens (named for iconic Scots-Canadian animator Norman McLaren, an alumni of the famous Glasgow School of Art which was in the news for the saddest of reasons recently), because it is a chance for these film-makers to have their work seen by an audience (and it is the audience who comes along to support them who get to vote on the award) and by the wider industry, a chance for them to be noticed by possible future employers and collaborators, and we need that kind of encouragement and celebration of creative work in all levels of our film-making if we still want to have such creators in years to come.

The McLaren Award for best British animation went to Peter Peake for his Take Rabbit, a film exploring an age-old conundrum: a man attempts to transport a fox, a rabbit and a cabbage across a river in his tiny boat but soon realizes he’s taken on more than he bargained for. The film features the vocal talents of Matt Berry, Amelia Bullmore, Stephen Graham and Steve Pemberton. Winner of the Award in both 1994 and 1998, with Pig and Pog and Humdrum respectively, Peake has also garnered Oscar and BAFTA nominations for his work.

Check out my blog and you can follow me on Twitter.