Reproduction and the Maternal Body in the Alien series

This in-depth and fascinating analysis of the Alien films is by Paul Jonze.

Introduction

There’s nothing to fear. Look, no blood, no decay. Just a few stitches.

– Dr. Henry Frankenstein, Frankenstein

Futura … Parody whatever you like to call it. Also: Delusion … In short a woman.

– Inventor Rotwang, Metropolis

The image of the ‘monstrous-feminine’, or femme castratrice, has been prevalent within the science fiction and horror genres since the era of the silent film. When the scientist Rotwang created Maschinenmensch, (or ‘the Machine-Man’), otherwise known as Maria, in the German Expressionist epic Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927), the expressionless yet sexual representation of woman became the subject of both attraction and repugnance alike. This representation of the female monster would later become the subject of many B-movies, however in large part, she served mainly as a counterpart that remained in the shadow within the male dominated world of horror until the 1950s. Films such as Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935) and Brides of Dracula (Terrance Fisher, 1960) are significant examples of women serving as monstrous consorts under male subjugation. However, film theorist Barbara Creed argues that the manifestation of the monstrous feminine is not always in the guise of the horrific body as found in the B-movie:

The female monster, or monstrous-feminine, wears many faces: the amoral primeval mother (Aliens, 1986); vampire (The Hunger, 1983); witch (Carrie, 1976); woman as monstrous womb (The Brood, 1979); woman as bleeding wound (Dressed To Kill, 1980); woman as possessed body (The Exorcist, 1973); the castrating mother (Psycho, 1960), woman as beautiful but deadly killer (Basic Instinct, 1992), aged psychopath (Whatever Happened To Baby Jane?, 1962), the monstrous girl-boy (A Reflection of Fear, 1973); woman as non-human animal (Cat People, 1942); woman as life-in-death (Life-force, 1985); woman as the deadly femme castratrice (I Spit On Your Grave, 1978).

(Creed, 1993: 1)

As Creed’s statement illustrates, the appearance of the monstrous-feminine as protagonist appears on film most notably at the beginning of the 1960s. One could argue that this manifestation directly correlates with what became known as the second wave of the feminist movement.

Alongside the symbolic representation of the monstrous-feminine, the maternal body is displayed as a tool to tap into male anxiety surrounding birth and reproduction. The invention of new life has been evident since the early days of cinema, when the maniacal Dr. Frankenstein uttered the famous words “It’s alive!” in James Whale’s film adaptation of Frankenstein (1931). This portrayal was man’s attempt at playing God, creating existence with his own hands, constructing a false womb, an unnatural space to grow life, and is a significant example of man’s preoccupation with birthing rites. The maternal body differs from that of the male, as it possesses the natural ability to carry, nurture and produce life through its own biological functions.

The Alien series demonstrates male anxiety surrounding the materialization of the maternal, the monstrous, and the horror of the open body within the grand narrative of each instalment. These anxieties have been represented on screen as spaces of horror and trauma directly related to the human body, and throughout the series have been presented as themes relatable to contemporary developments in real-life social politics and scientific advancements. Barbara Creed’s reading of the maternal body in the horror genre analyses the repulsion of reproduction, using Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection to exemplify her argument:

The place of the abject is ‘the place where meaning collapses’, the place where ‘I’ am not. The abject threatens life; it must be ‘radically excluded’ (Kristeva, 1982, 2) from the place of the living subject, propelled away from the body and deposited on the other side of an imaginary border which separates the self from that which threatens the self. Although subject must exclude the abject, the abject must, nevertheless, be tolerated for that which threatens to destroy life also helps to define life. Further, the activity of exclusion is necessary to guarantee that the subject take up his/her proper place in relation to the symbolic.

(Creed, 1993: 9)

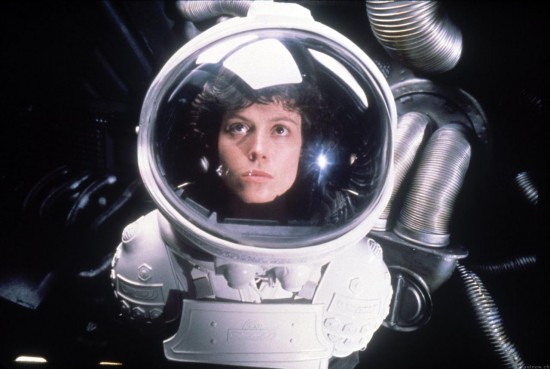

Creed’s argument of the maternal body as a space of horror uses Kristeva’s theory of the abject to illustrate the anxiety surrounding reproduction. However, this thesis, while also using Creed and Kristeva’s theories of the maternal and the abject to demonstrate anxiety concerning procreation, will also establish reproductive medica-social influences and contexts that are contemporary to each film. Chapter one will focus on Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) and its themes of reproduction, abjection and the archaic mother that are established in the film, which underline the themes of its subsequent sequels. The chapter will demonstrate how real-life advancements in medicine can be applied to the film’s narrative of reproductive anxiety, and will examine the presence of the reoccurring protagonist Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) who appears in all four instalments. Chapter two will explore Ripley’s transformation from integrated science officer to significant feminist icon of the Reagan-era in Aliens (James Cameron, 1986), and her relationship with Newt and the Alien Queen, comparing the parallels between fiction and real life advancements in surrogacy. The third chapter, analysing Alien 3 (David Fincher, 1992), will examine the film’s underlying subtext concerning the early 1990s emergence of HIV and infestation, and the final chapter will examine the Alien series’ concluding instalment, Alien Resurrection (Jean Pierre Jeunet, 1997), and the themes of cloning which are a central premise of the film’s narrative.

Although Creed’s theory of reproduction and maternal manifestation form a blueprint for this thesis’ argument, this work will broaden the period and take into account additional themes of contemporaneous medical anxiety, especially focusing on reproductive technologies. It will illuminate how the films are not just an illustration of the monstrous, but also a reflection of real life unease that has moved on from and extended Creed’s view of the abject into the more tangible territory of reproductive technologies.