SpielBLOG: Empire of the Sun – A Steven Spielberg Retrospective

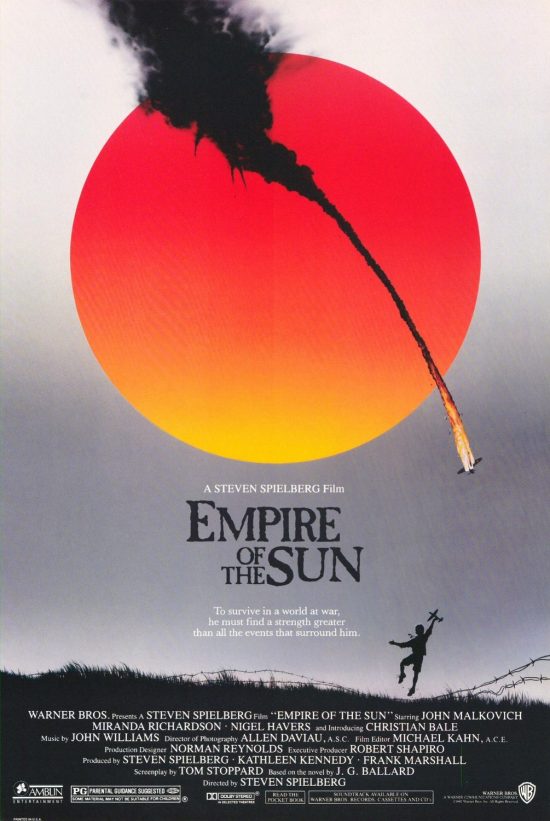

There’s a rhyming in the posters of E.T.: the Extra-Terrestrial and Empire of the Sun. The big moon is replaced with the big sun; the silhouetted child on the bike is now a silhouetted boy and the Michelangelo inspired contact between the alien finger and the human finger is now a near meeting of the boy’s toy airplane and the kamikaze fighter returning to the Earth in flames. Fantasy and reality – youth and death.

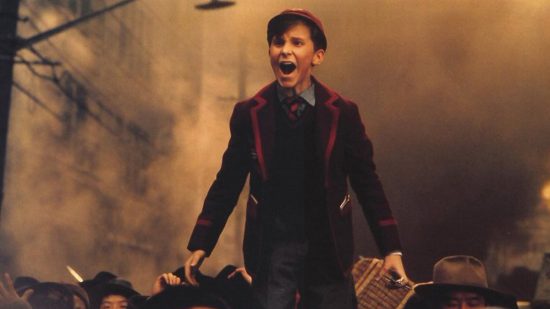

The two films have a lot in common. They are about children who are essentially alone and look toward an alien other for an alternative identity and escape. Already, before the Japanese invasion brings disaster to the British and allied civilians living in Shanghai, we find Jamie/Jim (future American Psycho and Batman Christian Bale) alternately yawning through choir practice and singing with an angelic voice. Unlike Elliot, Jamie is an obnoxious and spoiled brat. He treats the Chinese servants with careless entitled racism and though he is aware of the war and poverty, he is as aloof as his parents, or for that matter any of their upper-class friends who go to costume parties while cholera rages and the rest of the country is under the control of the Japanese invaders. Stiff upper lip and all that.

Spielberg never tries to make Jamie likeable. He has his dreams of flight and his free-spirited resilience, but Jamie is the most unchildlike of Spielberg’s children, anticipating the camp children of Schindler’s List. Tom Stoppard’s screenplay stays close to JG Ballard’s autobiographical novel, although the novel itself strayed from his real-life experiences significantly. For instance, Ballard’s parents were with him in the camp, whereas Jamie is separated from them, here and in the book, at an early point.

The adult world is absent following the Japanese invasion and Jamie enjoys a brief moment of liberation, cycling around his large house, but food soon begins to run out and he must stray back into the city and seek help once more from adults. Basie (John Malkovich), a gleefully selfish American, befriends him. However, his self-serving amorality is just a sliver too far away from humanity for Jim, though he’s at least more charismatic than Nigel Havers’ priggish doctor. The truth is that Jim really needs no father figure. Once he gets himself safely imprisoned, Jim gets along just fine in the camp. In fact, he thrives much better than the adults around him, including a married couple who also half-heartedly adopt him.

The English represents a failing empire of weakness, arrogance and defeat. The fight is really between the worldly egotistic ascendancy of the Americans and the fascist neatness and sacrifice of the Japanese, with the English as befuddled bystanders, clutching to their irony in the midst of irrelevance. Sound familiar?

Rather than the doctor or Miranda Richardson’s narky Mrs. Victor, Jim is drawn more to both the Japs and the Yanks. Basie looks like a character from his comic books, and the Japanese pilots preparing for their suicide missions seem like visions from his dreams.

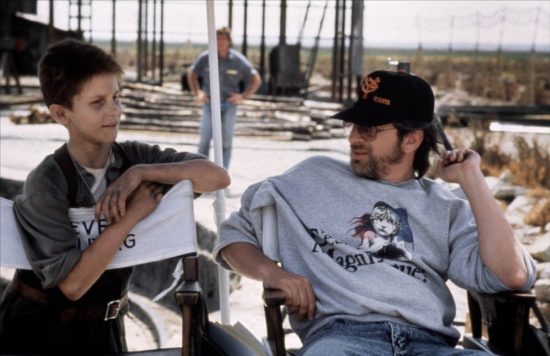

The film was originally going to be directed by David Lean and Lean is an obvious touchstone, as well as a frequent visitor to the set. Another of Spielberg’s surrogate dads. Like Kubrick, he was one of the older directors flattered by the younger man’s praise and also called on to provide guidance as well as inspiration. Spielberg had Bridge Over the River Kwai in mind as an immediate model. As Alice Walker had approved of The Color Purple, so Ballard was invited on set and given a cameo (pictured to the left) at the fancy-dress party Jim’s parents attend. He liked the picture and particularly thought Christian Bale’s performance was excellent. And indeed, it is. Bale manages to grow as the film progress. The polished schoolboy, precociously proclaiming himself an atheist and wanting to write a book on contract bridge, becomes something of guttersnipe, a latter-day artful dodger, a scruffy survivor who nevertheless retains his integrity as the world falls apart around him.

The film was originally going to be directed by David Lean and Lean is an obvious touchstone, as well as a frequent visitor to the set. Another of Spielberg’s surrogate dads. Like Kubrick, he was one of the older directors flattered by the younger man’s praise and also called on to provide guidance as well as inspiration. Spielberg had Bridge Over the River Kwai in mind as an immediate model. As Alice Walker had approved of The Color Purple, so Ballard was invited on set and given a cameo (pictured to the left) at the fancy-dress party Jim’s parents attend. He liked the picture and particularly thought Christian Bale’s performance was excellent. And indeed, it is. Bale manages to grow as the film progress. The polished schoolboy, precociously proclaiming himself an atheist and wanting to write a book on contract bridge, becomes something of guttersnipe, a latter-day artful dodger, a scruffy survivor who nevertheless retains his integrity as the world falls apart around him.

Empire of the Sun is a fever dream. Violence happens, beatings are handed out to Basie twice and the doctor once, there’s sickness and real hunger; bombs explode, people play dead and then the next day they are. The attacks from the sky instead of being terrifying are exhilarating for Jim – ‘Cadillac of the Skies,’ he yells as the Americans bomb the Japanese airstrip near the camp. The nuclear blast which ends the war is witnessed in a graveyard of stuff – pianos, chandeliers, old Rolls-Royces. The old order has been eliminated at a stroke, but Jim feels more excitement than dread. ‘I learned a word today,’ he says having witnessed the white blast from Nagasaki. ‘Atomic bomb.’

Nowadays the film holds up partly because of its pre-CGI grandiosity – the crowd scenes and period detail are masterfully done – but mainly it’s because of the unsentimental perspective which we end up sharing with Jim. We understand that by the end of the film, Jim should be reunited with his family but there is something strangely muted about the happy ending, as if the family no longer truly recognizes their child. This new mature and darker tone can partly be attributed to collaborators such as Ballard and Tom Stoppard, the latter would become a constant script doctor for Spielberg, and the influence of Lean who always had a generous misanthropic streak throughout his grandeur. But Spielberg himself was capable and ready to look at the darkness of recent history and human nature without resorting to an over-leavening of humor or sentimentality, as he had done in The Color Purple. Having gone so dark, however, he can be forgiven for wanting to return to something lighter and a film which would involve and much happier, family reunion.