Steven SpielBLOG: The Sugarland Express

In the early seventies, a debut movie was released of a young filmmaker. Based on a true story, it told the slim tale of two naive young lovers from Texas who go on the run from the law and become the targets of a media frenzy as they are pursued. The film was called Badlands and the director’s name was Terrence Malick. The similarity in subject matter with Steven Spielberg’s debut feature The Sugarland Express meant that Pauline Kael reviewed both films together in The New Yorker. Kael didn’t much care for Malick’s first film comparing it unfavourably to Spielberg, even though her praise of Spielberg was peppered with arch insult: “I can’t tell if he has any mind, or even a strong personality, but then a lot of good moviemakers have got by without being profound.”

Her argument was that as a craftsman and an entertainer – both of which counted as faint praise from Kael – Spielberg was one of the most promising debuts in a long time. He was a product of a Hollywood machine, albeit one that was firing on all cylinders and would produce some of the best films ever made over the span of a decade. In fact, watching the film today, it seems easy to imagine it could have been the work of Robert Altman or Arthur Penn.

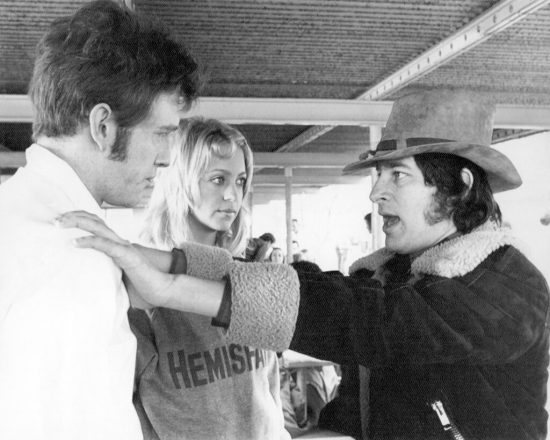

Famous TV comedian, Goldie Hawn was the star attraction as Lou Jean Poplin, a single mother, petty criminal who decides to break her husband Clovis (William Atherton of later Ghostbusters infamy) out from a low security prison in order to rescue their baby who has been placed in foster care. Lou Jean and Clovis have no grand plan and their witless progress is only facilitated by the overkill of the response of the authorities, moderated by the restraint of Captain Tanner (a fantastic Ben Johnson). Having stolen one car and totalled it, they then steal the car of Patrolman Slide (Michael Sacks), who was pursuing them, and – taking him hostage – head for Sugarland where Baby Brandon is feeding steak to the family dog. They’re pursued by an increasing convoy of police cars, as well as a TV news team and ultimately crowds of well-wishers.

The photography is superb, celebrated cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond can take some credit, but Spielberg’s shot choice is already there. His ability to tell a story visually, to marshal background detail and juxtapose different elements, to find beauty and grime in the same location is truly stunning, justifying Kael’s enthusiasm.

Though the film would pick up Best Screenplay at Cannes, this is probably its weakest element. The characters aren’t well drawn and at crucial moments make staggeringly dumb decisions. Whereas Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek imbue their leads with an edge of sociopathic charisma in Badlands, here Hawn and Atherton come over as doomed lovers via Dumb and Dumber. To be fair, Atherton seems the most knowing of the two, occasionally his expression betraying that he knows how this is going to end but he’ll go for it anyway. But just when the possibility of pathos scratches the corner of your eye, he’ll prove himself as dumb as a brick in the next scene. (He would later reappear as the eminently hateable asshole in Die Hard and Ghostbusters.) Goldie Hawn, meanwhile, was reaching for a more dramatic role, but the character is underwritten and – crucially – irritating. Her squealing when delighted and hollering when angry are equally annoying and it is ultimately Lou Jean who is the motivating force for the dumbest decisions.

And then there’s the police cars. The excessive demolition derby of police cars seems to be an obsession in Seventies American Cinema. John Landis in The Blues Brothers for instance goes all the way. It’s the mad cap chase that would lead to such capers as Smokey and The Bandit, Convoy and The Cannonball Run. I can’t help but suspect Spielberg likes the look of the flashing strobes on the roofs of the cars and the different angles he can get from them. When Captain Tanner wants to show his contempt for a pair of duck hunting vigilantes, he smashes the strobe light on their car, like a general ripping the epaulettes from a disgraced officer.

As with Duel, Spielberg is consciously making as big a film as he can out of fairly slim material. However there the simplicity works in the film’s favour. Here, there is more ambition but paradoxically The Sugarland Express ends up as a smaller film overblown. A superficially embossed calling card which isn’t funny enough to be a comedy or thoughtful enough to have something to say or touching enough to work as a tragedy. There are glimpses of darkness on the edge of town. The two snipers brought in to assassinate the outlaws provide a brief glimpse of workmanlike malevolence, with the bullets stuck in their ears to protect them from the noise.

As a calling card it of course worked. It also significantly provided him with John Williams, still credited as Jazz musician Johnny Williams, the composer and collaborator who would contribute significantly to his future success. In fact, there probably isn’t a more recognizable theme in an original score as that which Williams would compose for Spielberg’s next film and his first major hit: Jaws.

Next up: Jaws

You can check out my blog and follow me on Twitter.

Buy Live for Films a coffee

Buy Live for Films a coffee